Matt Hancock has achieved fame in recent months for devouring a cow anus live on television (during his I’m A Celebrity stint) and for releasing questionable TikTok videos cringing about his past “embarrassing” moments.

Some will recall that before all this, he was once UK health secretary during the biggest global health crisis in living memory. Back then, he achieved notoriety for (among other things) allowing COVID patients to be sent into care homes and for securing lucrative testing contracts for his friends.

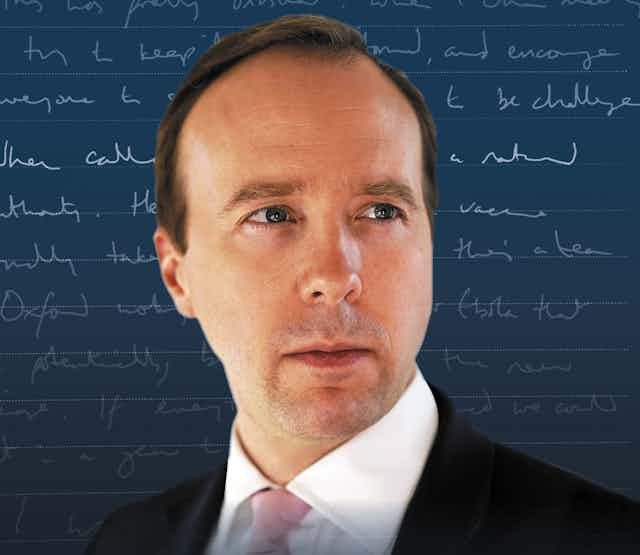

Now, Hancock has published his Pandemic Diaries, giving his side of the story. So what insights do they have to offer? And how might a literary historian like myself situate them within the wider context of the political memoir?

Early on in Hancock’s diaries, we learn that the UK Health Secretary’s first (and I quote) “oh shit” moment was on January 28, 2020, when he was told that the pandemic could lead to up to 820,000 UK deaths.

From then on in, the basic thrust of the narrative is that everyone but Matt Hancock was responsible for the litany of failures that ensued.

Delayed restrictions? That was the fault of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies. Dismal contract tracing? Public Health England were to blame. Failure to close UK borders? No. 10 was responsible. Government in chaos? That would be Dominic Cummings.

The Erin Brockovich of COVID

Reading how “aghast” Hancock was in response to a Prime Minister’s Questions session in early February, in which no one asked a single question about the virus, the impression given is that he was the Erin Brockovich of COVID.

Oddly enough, however, none of this quite tallies with Hancock’s account, in these same pages, of his actual activities during this period. Eating Babybels with Ronnie Wood at a Brit Awards ceremony in late February, for instance. Or going to Planet Laser in Bury St Edmunds in early March.

Or, more generally, entirely failing to respond to the knowledge that 820,000 lives were at risk by taking decisive action – in the process dismissing the advice of Tory grandees and former prime ministers, who (as Hancock acknowledges in his diaries) were sending desperate text messages demanding restrictions as early as February.

A possible explanation for these strange inconsistencies is the fact that Hancock’s diary isn’t actually a diary at all. As he himself admits, he “didn’t have time to keep a detailed diary” during this period - and so the Pandemic Diaries were “pieced together” after the fact.

Given the existence of an Imperial College study suggesting that the UK’s delayed response caused 21,000 unnecessary deaths, the pressure on Hancock to retroactively redeem himself seems clear.

So what to make of this strange attempt on the part of a disgraced politician, forced to quit in the wake of a scandal, to exonerate themselves?

The history of the redemptive memoir

Historian George Egerton notes that (while forerunners exist) the concept of the professional politician publishing a text that aims “to explain and interpret” the decisions they made in office didn’t find full expression until the 1890s, with first Chancellor of the German Empire Otto von Bismarck’s landmark three volume memoir.

Since then, accelerated by the “professionalisation” of politics during the early 20th century, the pressure to hold politicians to account has grown significantly. As Egerton writes, since the post-war period it has been the norm for politicians to “publish an account of their leadership”.

Hancock is hardly the first modern British politician to make use of this trend in an attempt to set the record straight. Tony Blair’s A Journey (2010) and David Cameron’s For the Record (2019) are just two recent examples.

What is perhaps unique about Hancock’s contribution to the genre is its fundamental unseriousness.

This is not just in the lack of willingness to take any responsibility for the mishandling of the pandemic, or in the fact that inventing a diary is an astonishing feat of post factual audacity. It is in the general ridiculousness of the account that is offered.

Less redemption, more slapstick

The image that will stay with most readers of Hancock’s diaries is unlikely to be that of a nation bravely facing a crisis.

The picture that has been indelibly imprinted upon my mind, for instance, is instead of Hancock struggling “to keep a straight face” at the sight of Thérèse Coffey “chomping on a sandwich” during “an extremely important” Zoom meeting about shielding the vulnerable.

Or of Hancock delivering his instructions as Health Secretary from “a director’s chair with ‘Hancock’ across the back”, gifted to him by Pinewood Studios.

Or of George Osborne whispering into Hancock’s ear how much he reminds him of “Tigger from Winnie the Pooh”.

Of course, the slapstick is on theme for the current Conservative Party: it’s evocative of Michael Gove’s skits on BBC breakfast, or Grant Shapp’s Elf on the Shelf routine, or Boris Johnson’s Love Actually parody.

The “total bants” is perhaps less expected in a diary account of a series of events leading to over 200,000 deaths. But then, the cow’s anus was unexpected too.