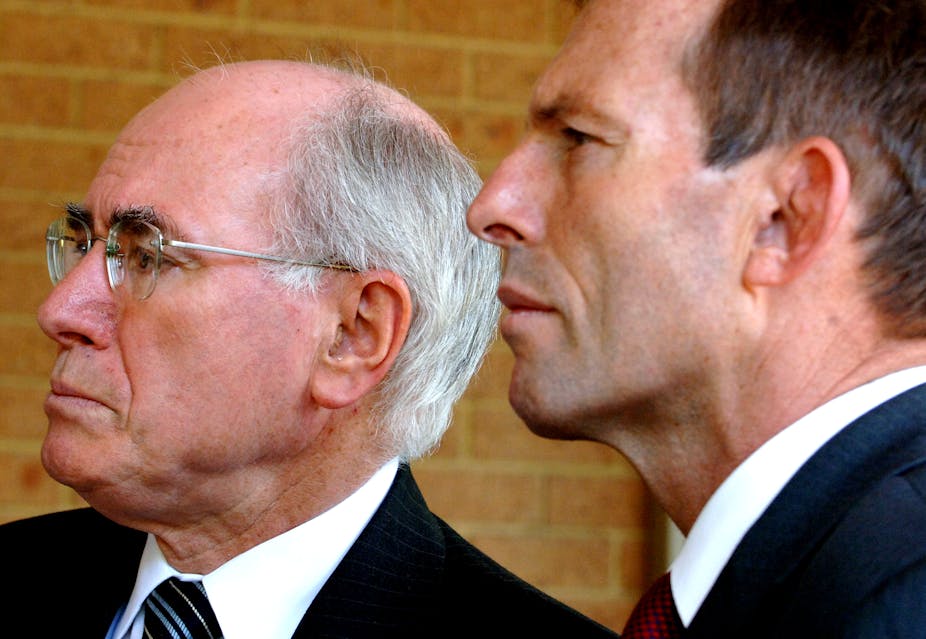

The Coalition revealed little of the new government’s health agenda during the election campaign, but Tony Abbott was minister for health and ageing in the Howard government from October 2003 until the 2007 election. So what can Abbott’s time in one of the most difficult portfolios reveal?

Abbott the political fixer

Former prime minister John Howard moved Abbott to the health portfolio to solve a major political problem for his government. Bulk-billing rates – allowing patients to access general practitioner services without direct charge – had been falling steadily under the Howard government in preceding years.

Many saw this as a deliberate attempt to undermine universal access to Medicare. That perception was strengthened when Howard repeatedly referred to Medicare as a “safety net”.

By late 2003, bulk billing had fallen to 66%, from its peak of 80% under Paul Keating’s Labor government (1991 to 1996). These rising out-of-pocket costs for visiting a GP fuelled discontent with the government.

Abbott was given instructions and the funds to reverse this problem. Increasing rebates to GPs quickly reversed the tide. By 2004, bulk billing rates were back over 70% and Abbott declared the government was now “Medicare’s greatest friend”.

Out-of-pocket costs were also hitting consumers who used specialist services – again through charges well above the rebate offered by Medicare. The Medicare Safety Net – which gave an additional subsidy if costs of specialist in-hospital services passed a threshold – was intended to fix this problem.

With no control over specialists’ fee-setting, this proved a recipe for further fee inflation and much of the benefit went to those who were better off.

Abbott the reformer

The early Howard years were marked by some significant reforms in health – not just the cut backs which grabbed the headlines. Then health minister Michael Wooldridge pushed through some important improvements in vaccination policy, effectively ending the very low levels of childhood immunisation.

With more controversy, Howard’s private health insurance changes reversed the abandonment of the private system. Membership of private health funds fell to just over 30% in December 1998. With a mixture of financial carrots and sticks, private insurance peaked at 46% in December 2000 - and has remained at around this level ever since. This also generated a largely new for-profit private hospital industry.

The Abbott years were less noted for new reform directions. Abbott himself was unsympathetic to the new public health push from the World Health Organization, aimed at the social determinants of health.

He saw health as a matter of individual choice, and ill-health in medical terms around the prevention and cure of particular diseases.

In 2006, Abbott rejected a half-hearted push from Labor state health ministers for restrictions on junk food advertising to children as a move to the “nanny state”.

True to his highly political approach to the portfolio, the reforms Abbott can claim were driven by election timing. Colorectal (bowel) cancer screening had a substantial amount of research and successful pilot schemes behind it.

It was added to the Coalition’s 2004 election promises, partly to meet the attractions of Labor’s Medicare Gold – which promised to end waiting lists for over-75s.

At the same time, the government subsidy to cover private health insurance premiums was increased for members over 65 and even higher for those over 70.

Much has been made of Abbott’s conservative Catholic faith and opposition to abortion. He has always argued that private beliefs could be expressed, but not imposed on a reluctant majority.

The only exception was the controversy over the availability of the abortion pill, RU486.

Abbott fought to keep ministerial discretion over the availability of such drugs – making the much-quoted observation he would have to be convinced that doctors were not presenting abortion as an “easy option” before prescribing a “backyard miscarriage”.

His veto powers were removed after a major revolt led by women parliamentarians from all parties.

Abbott the centralist

Abbott ended his term of minister as he began – focused on politics rather than substantive policy. As Labor’s demands for a more national approach to hospital policy mounted, Abbott responded by upping the ante , declaring that:

the only big reform worth considering is giving one level of government – inevitably the federal government – responsibility for the entire health system.

He was quickly silenced on this by Howard, who had no intention of entering the mire of federal state relations and the management of hospital systems.

The last echo of this centralist instinct came during the 2007 election campaign. Responding to very local community complaints about the reduction of scope of services at the Mersey Hospital in Devonport, Tasmania, Abbott moved to take direct federal control of the hospital. The state Labor government jumped at the chance to off-load an expensive white elephant.

Health has always been a difficult area for the Coalition parties. Their hostility towards Medicare played a major part in electoral failures from 1984 to 1993. Abbott’s period as health minister showed him as a pragmatist, primarily (and successfully) focusing on removing health from the front pages.

Jim Gillespie’s latest book Making Medicare: The Politics of Universal Health Care in Australia, co-authored with Anne-Marie Boxall, was published this month by UNSW Press.