Language is about much more than just about talking to each other; it’s one of the bases of identity and culture. But as the world becomes increasingly globalised and reliant on technology, English has been reinforced once again as the lingua franca.

The technological infrastructure that now dominates our working and private lives is overwhelmingly in English, which means minority languages are under threat more than ever.

But it might also be true that technology could help us bring minority languages to a wider audience. If we work out how to play the game right, we could use it to help bolster linguistic diversity rather than damage it. This is one of the main suggestions of a series of papers, the most recent of which looks at the Welsh language in the digital age.

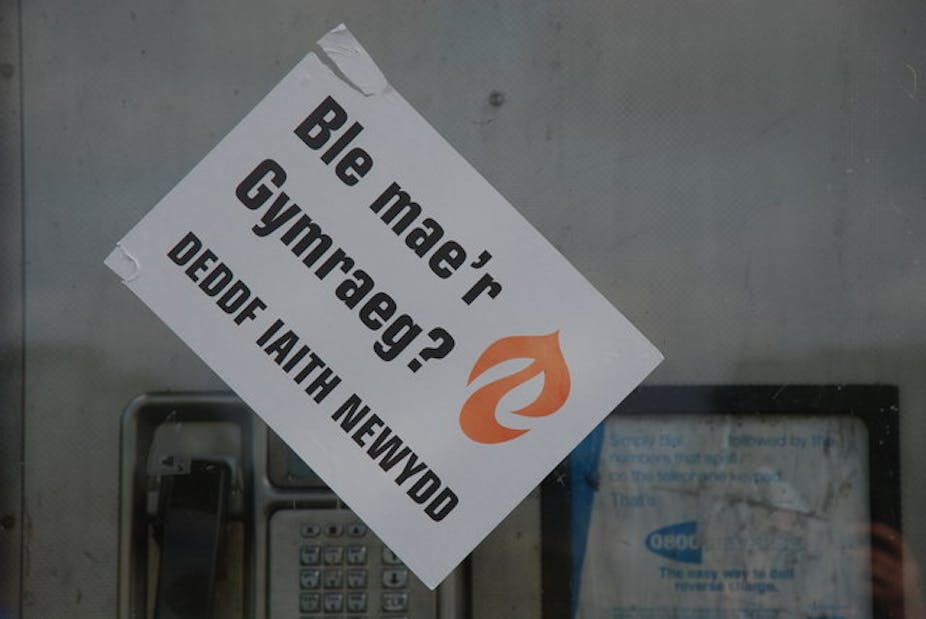

Welsh was granted official status in Wales by the Welsh Language Measure 2011. This builds on previous legislation that sought to ensure that bodies providing a service to the public in Wales – even those that are not actually based in Wales – must to provide those services in Welsh.

As more public services go online, the language in which those services are presented is all important. At the European level, around 55 million speak languages other than one of the EU’s official languages. In the UK, the total speakers of Welsh, Cornish, Scottish Gaelic and Irish number hundreds of thousands.

Language technology advances mean it will be possible for people to communicate with each other and do business with each other, even if they don’t speak the same language.

Technology fail

These language technology and speech processing tools will eventually serve as a bridge between different languages but the ones available so far still fall short of this ambitious goal. We already have question answering services like the ones you find on shopping sites, and natural language interfaces, such as automated translation systems, but they often focus on the big languages such as Spanish or French.

At the moment, many language technologies rely on imprecise statistical approaches that do not make use of deeper linguistic methods, rules and knowledge. Sentences are automatically translated by comparing a new sentence against thousands of sentences previously translated by humans.

This is bad news for minority languages. The automatic translation of simple sentences in languages with sufficient amounts of available text material can achieve useful results but these shallow statistical methods are doomed to fail in the case of languages with a much smaller body of sample material.

The next generation of translation technology must be able to analyse the deeper structural properties of languages if we are to use technology as a force to protect rather than endanger minority languages.

Chit chat to survive

Minority languages have traditionally relied on informal use to survive. The minority language might be used at home or among friends but speakers need to switch to the majority language in formal situations such as school and work.

But where informal use once meant speaking, it now often means writing. We used to chat with friends and family in person. Now we talk online via email, instant messaging and social media. The online services and software needed to make this happen are generally supplied by default in the majority language, especially in the case of English. That means that it takes extra effort to communicate in the minority language, which only adds to its vulnerability.

Enthusiasts are live to this problem and crowdsourced solutions are emerging. Volunteers have produced a version of Facebook’s interface in Welsh and another is on the way for Twitter, so who knows what might be next?

It’s also possible for language technologies to act as a kind of social glue between dispersed speakers of a particular language. If a speaker of a minority language moved away from their community in the past, the chances of them continuing to speak that language would have been dramatically reduced. Now they can stay in touch in all kinds of ways.

More and more, communities are developing online around a common interest, which might include a shared language. You can be friends with someone who lives hundreds of miles away based on a shared interest or language in a way that just wasn’t possible 20 or even ten years ago.

Unless an effort is made, technology could serve to further disenfranchise speakers of minority languages. David Cameron is already known to be keen on an iPad sentiment analysis app to monitor social networks and other live data, for example. But if that app only gathers information and opinions posted in English, how can he monitor the sentiments of British citizens who write in Welsh, Gaelic or Irish?

On the cultural side, we need automated subtitling for programmes and web content so that viewers can access content on the television and on sites like YouTube. With machine translation, this could bring content in those languages to those who don’t speak them.

All this is going to be a big job. We need to carry out a systematic analysis of the linguistic particularities of all European languages and then work out the current state of the technology that supports them. But it’s a job worth doing.