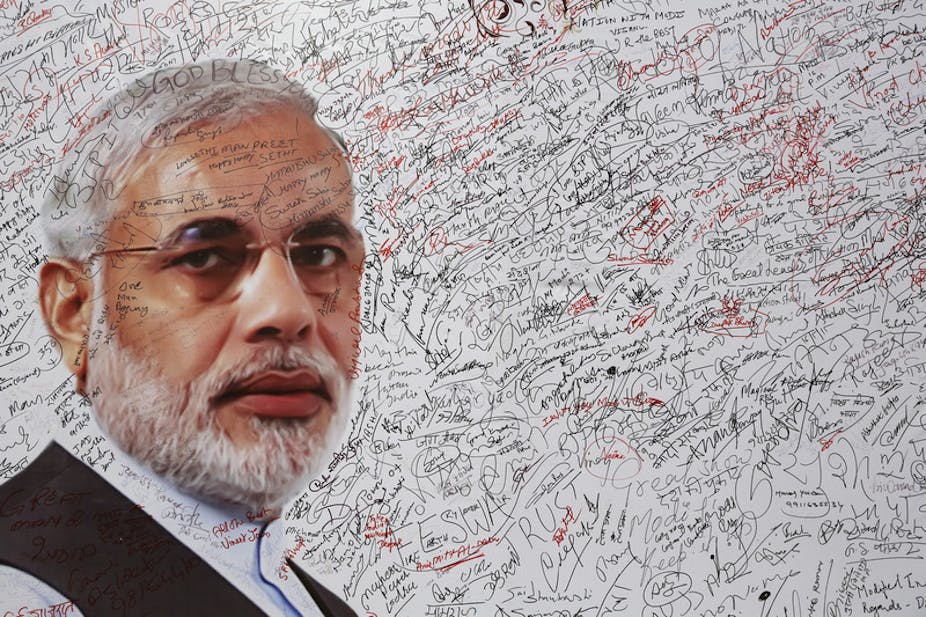

Narendra Modi, the man whose campaign to become prime minister divided and electrified the people of India, released an anthology of his poems in an English translation last month. Modi has been writing poems for many years, and a Gujarati selection – Aankh aa dhanya chhe (Our eyes are so blessed) – appeared in 2007, when he began his third term as chief minister of Gujarat.

He is sufficiently proud of the poems that he has placed a complete version of the Gujarati book on his official website; he likes to give recitations of his poems and frequently quotes from them in his speeches.

Commentators point out, correctly, that these poems are more artful than the compositions of Atal Behari Vajpayee, the last BJP politician to have served as prime minister, but far less accomplished than the verses of any major Indian poet.

The journalist Aakar Patel has likened Modi to the emperor Nero. Nero had a deluded sense of his own talent, he persecuted Christians, and he fiddled while Rome burned. In Modi’s case, the town was Ahmedabad. Judges in the Supreme Court of India have also made the comparison between Nero and Modi’s administration in Gujarat.

The poems offer numerous abstractions and make few overt references to political events or conflicts. (Among the exceptions is “Kargil”, an unashamedly patriotic poem in which the hot-blooded courage of Indian warriors transforms the frozen landscape.) In the foreword to the English edition, Modi speaks of his poetry as “streams of thoughts” – a phrase which many newspapers rendered, intriguingly, as: “screams of thoughts” – and claims they represent: “things I have witnessed, experienced and sometimes imagined”.

At one level, the poems are ruminations on grief, regret, and happiness or they explore such topics as nature and divinity. No one familiar with the history of literature will be surprised to find these themes treated in poetry, even in a politician’s poetry. So, in “Bliss”, the narrator imagines himself flying high into the heavens or descending into the ocean’s depths, while, in “Dawn of Wonder”, he heralds the arrival of a “brave new dawn” and celebrates his faith in Ram.

Yet, Modi himself has contributed to an environment in which nature and divinity have become more politicised than ever before, in which grief can find little or no consolation and in which regret can never be expressed in any language. He writes of bees, flowers, and rivers but allocates land and natural resources to companies faster than any previous head of Gujarat. He writes about the pain of separation but declines to acknowledge his wife for over 40 years until compelled to do so by electoral circumstances. He expresses his piety at length but still cannot bring himself to act contrite over the murderous violence that cost hundreds of Muslims their lives in 2002. In such a scenario, what can poetry be?

Shall we cast our criticism purely in poetic terms and set aside our reservations of the man’s politics? You cannot forget who the poet is, even if that were possible, when every medium has proclaimed his achievements this election season. Modi is capable of an interesting turn of phrase or a striking metaphor and, for all the clichés he employs, appears to strive for emotional depth and acuity. But the poems are also fantasies, fantasies of evasion, fantasies in which the narrator ranges all over the earth and heavens and at the same time asserts his toughness and rightness. This is from “Bliss”, in Ravi Mantha’s new translation:

We soar high when we please

Or explore the ocean’s cool depths.

We become the sun rising above the mountain top,

Or rise in silence in the starlight.In bliss we show no shyness, no attention to form.

We are a caravan, an endless bounty of love.

The wise of this world perceive us as mad,

They do not lie; yet, we are true.

And this from “Renunciation”:

Wander this night, roam this earth

In the dark, chant, walk alone.

Leave this speech, leave these meanings

Break the barriers and move free.

The narrator frequently expresses his desire to slip away from the world of conflict, to achieve a kind of bliss that is both solitary and shared, and to commune with the divine. But the hardness in the tone makes it difficult to read these verses as the representation of some inner struggle in Modi or to think of them as the yearnings of a man who would throw away power if only he could locate the softness in his soul.

These are the writings of a man who remains confident in his ability to know what Ram wants and who is assured of the future that lays open before him. He seeks to describe human experience but shows few signs of self-doubt or ignorance or weakness; he recognises that different people have different truths but also knows how to secure his own great truth.

We celebrate the dawn today

And a brighter tomorrow.

In this confident vein, the narrator of “Verb” tells us who he is and what he accomplishes (the first two lines are a loose translation of the Gujarati):

I am a man of action

Even when I write,

I draw a circle of words

And then I make the circle a square.

In that circle which is now a square

I place words, colourful, smooth as marbles

These words of glass

Are words of truth—like tears

They form a period at the end of a sentence.

Near lie the adjectives, within the confines of a Lakshman Rekha

They keep the piety of Ram

Adjacent to them the nouns keep playing

A game of tic-tac-toe. I keep the verb in the centre,

And then I draw one endless circle, resolute.

The Lakshman Rekha, according to later versions of the Ramayana, is a proverbial expression for the line that you’re not supposed to cross. Is the narrator suggesting that he both draws lines in the sand and chooses when to cross them?

This kind of writing, in surer hands, can pose sophisticated questions about transgression and poetic language, but here the author promises a complexity that he cannot quite deliver. The poem hints at depths but merely offers “words of glass” as “smooth as marbles”.

It’s true that the narrator presents himself as a man of action who can turn circles into squares and manipulate words at will. We more or less suspected that from the poetry. But by keeping himself in the centre, he also says that he wants to remain in the limelight for all time.