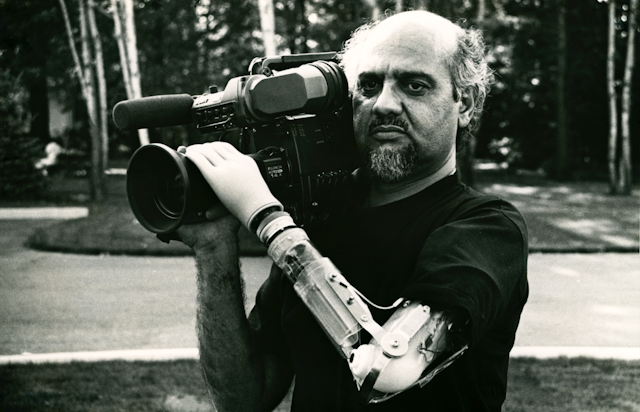

Kenyan photojournalist Mohamed Amin (1943-1996) rose to fame for documenting the 1984 famine in neighbouring Ethiopia with powerful images of the tragedy. He also captured the Ethiopian people’s suffering during the brutal reign of Mengistu Haile Mariam. These images, broadcast by the BBC, shocked the global public and had a significant international impact. They mobilised governments, individuals and institutions. This even led to Live Aid – the famous 1985 benefit concert to raise funds for victims of the famine.

As a result, some sources refer to Amin as “the man who moved the world”, reducing his visual work to this tragedy. As a lecturer and researcher in journalism, and a photographer and scholar completing a PhD on Amin, we recently published a paper on Amin’s vast earlier body of work.

We wanted to highlight that Amin had already undertaken intense and prestigious work in Africa, Asia and the Middle East before these photos of tragedy. His visual collection, spanning from 1956 to 1996, comprises over 8,000 hours of video and approximately 3.5 million photographs.

It’s important that people understand the greater scope of Amin’s images: he captured the first shots of African lives after European imperialism. If French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson was considered the eye of the world, Amin is the eye of postcolonial Africa.

International fame

On 23 October 1984, the UK public broadcaster, the BBC, aired a shocking report by journalist Michael Buerk, featuring images by Amin, on the Korem refugee camp in Ethiopia:

Death is all around. A child or an adult dies every 20 minutes. Korem, an insignificant town, has become a place of sorrow.

Ethiopia was under the Marxist dictatorship of Mengistu Haile Mariam, who had ousted the last Ethiopian emperor, Haile Selassie, through a military coup in 1974. In 1984, the country still had restricted areas for foreign media, but the BBC correspondent had been taken to the Ethiopian highlands by connections of Amin, a Kenyan cameraman and photojournalist.

The impact of the report was extraordinary. A story set in a developing country with no British angle was viewed by nearly a third of the adult British population. The images were quickly replicated by other international TV networks. Soon enough 425 TV channels worldwide had broadcast Amin’s images to a global audience of 470 million people. “Mo” Amin was making history. He had become the cameraman of the Ethiopian famine.

The images catalysed the largest humanitarian relief effort the world has ever witnessed. Public visibility turned Amin into an international celebrity. He and his family were received at the White House in the US in 1985. At the ceremony, US vice-president George Bush officially presented the cameraman with a symbolic cheque for two billion dollars in humanitarian aid for Africa.

Earlier work

Interest in Amin’s work stems from three main aspects. The first is his vast and diverse body of work. The second is his focus. He centred on Africa, outside the western media’s epicentre, with a pan-African perspective. The third is that his images capture postcolonial events as they unfolded, in a time before the mass globalisation of the internet and social media. His postcolonial coverage of African dictators, such as Jean-Bédel Bokassa (in the Central African Republic), Mobutu Sese Seko (Congo) and Idi Amin (Uganda) exemplify the importance of his earlier work.

The two main themes of his work are postcolonialism and everyday Africa. From the 1960s to the early 1980s, in the early period of African independence, his response to the western media’s portrayal of Africa was to create photo books that showed everyday African life from an African perspective. These publications allowed him to give his work a personal and pan-African orientation, freeing it from the daily urgency of serving western news interests. He created a total of 55 books of his own work.

His book Cradle of Mankind (1981) was the outcome of an expedition he led, considered to be one of the first circumnavigations of Lake Turkana and its desert to the north of Kenya. The aim of this adventure was to document the life of the six tribes living along the shores of the lake. The book was accompanied by exhibitions in Nairobi and London. The expedition earned him the honour of being admitted as a member of the Royal Geographical Society of London in 1982.

His documenting of African dictators reveals another extraordinary body of work, the camera up close and personal. The dictator Idi Amin, for example, granted him three exclusive personal interviews (in 1971, 1980 and 1985).

He also journeyed far beyond the continent. His works on Asia and the Middle East include books on Mecca (1980) and The Beauty of Pakistan (1983), among others.

Amin’s legacy

There is a constant stream of references to Amin’s work in the media, a couple of biographies have been written about him, and his images are constantly used to illustrate books and articles on tourism, nature or history. However, there are few academic studies of his work and fewer still international retrospective exhibitions.

Currently, it’s possible to access just a small portion of his work online. In 2021, 25 years after his death, the Mohamed Amin Foundation made 6,553 digitised images available in 58 thematic reports and galleries through Google Arts & Culture. This is a small step towards showing his complete body of work.

The global impact of Amin’s photos and videos concerning the Ethiopian famine is undeniable. However, it’s important to emphasise that his broader legacy constitutes one of the single most extensive historical photographic archives of Africa ever created – and it deserves greater attention.