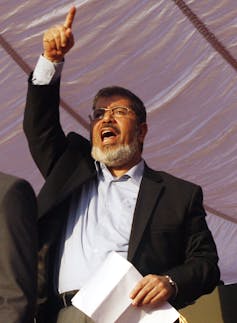

The quick and ruthless deposal of Mohamed Morsi is testament to two realities of post-Mubarak Egypt: the broken economy and the deep-rooted political and economic interest of the armed forces.

When he assumed power last year Morsi made a lot of promises about how much things would improve for Egyptians. Learning no lessons from Western politicians, he stuck his neck out with a 100-day plan, pledging improvements in living conditions, food prices and security. Predictably, most of these ambitions proved unachievable in such a short period of time. His opponents started calling attention to the failures and the middle class Egyptians who helped oust Mubarak felt that their revolution had been betrayed.

The inability to quickly fix a broken economy and the appointment of cronies to plum jobs was causing resentment, even amongst those who had voted for the Freedom and Justice Party. The increased presence of Islam in politics may have been the focus of a lot of Western coverage, but for much of the Egyptian population this revolution, and the one before it, was all about jobs, food and a brighter future. When these dreams failed to materialise, talk of exercising the people’s will a second time began to grow.

Waiting in the wings

In truth the old guard never really left power. They were waiting in the wings and throwing the odd rotten tomato. A succession of legal challenges over the constitution, the parliament and the presidency was the strategy, forcing the frustrated President to over-reach in November and slide towards dictatorship. As discontent grew and inaction festered, Morsi and his party circled the wagons and tried to ignore their failing support.

But protestors were beginning to filter back to Tahrir Square and the head-in-the-sand strategy was doomed to failure given the powerful reach of the ancien régime. By fanning the flames of discontent with their rotor blades the military showed that it was listening to the people whilst simultaneously wedging out a president who represented a threat to their interests.

In Egypt the armed forces are something of an oligarchy, not just in terms of military strength but also in economic power. Factories, restaurants, stadiums, property development – all can be found on the books (and sometimes off them). Fostered under the cosy arrangements of the Mubarak years, military interests are estimated to be involved in somewhere between 15 and 40% of Egypt’s economy. In truth, nobody knows just how extensive the holdings are, but in a country known for its black and grey economies, the military is a significant player.

That’s a powerful motivational factor for stepping in and changing the rules when the game isn’t going your way. What would have been in the generals’ minds was how long it would be before the military leadership started being replaced with Morsi’s men. Would there come a time when all the leadership positions were just sinecures for Brotherhood buddies?

Field Marshall Tantawi was shunted into retirement in August 2012 and around 70 other members of the top brass also had their pension plans put into action. Rather ironically, Morsi chose the youngest and apparently tamest member of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces to be his new Defence Minister and Commander-in-Chief; a young officer called General Abdul Fattah al-Sisi. The same one who gave the podium speech announcing Morsi’s own removal from office.

A messy future

By deposing Morsi the generals are effectively setting the precedent for intervening whenever they don’t like the way that Egyptian politics is going. This arrangement is reminiscent of Turkey, where the army has stepped in more than once to remove governments they didn’t like. In Egypt the generals aren’t likely to want the poisoned chalice of leadership themselves. What they do want though is a return to the old days, where they can quietly and independently take care of business.

The anti-Morsi elements that ostensibly stand to profit from this coup will need to make their own deals with the generals, no doubt promising not to step on their toes. However it’s doubtful that any single opposition group could sufficiently unite the people to enjoy a strong mandate. That potentially means some messy coalitions, with all the vested interests and baksheesh they usually entail.

It would certainly be foolish to believe that the Muslim Brotherhood will now be ejected from the political scene. There is a wide swathe of the Egyptian population who are happy to see a greater Islamic influence in politics. Morsi may not be their man, but the sentiment and the ideology are still there. However, like their opponents, the Brotherhood and their party structure won’t be able to rule alone. Their track record of alienating opposition parties and other key demographics of the country will also need some reinvention.

For America and the West the challenge is what to do about all this. Democracy is a messy business, especially in places that are trying it out for the first time. Does America close its cheque book, especially when they would probably like to see a non-Islamist president anyway? If you espouse free and fair elections, what do you do when they are nullified?

More importantly, what chance is there for stability in Egypt in the next decade? With talk of re-designing the constitution and electoral system, the country is slipping back two years and starting all over again. The key question is how long will the next president have to fix those irreparable social and economic problems before he too might be ousted by the generals?