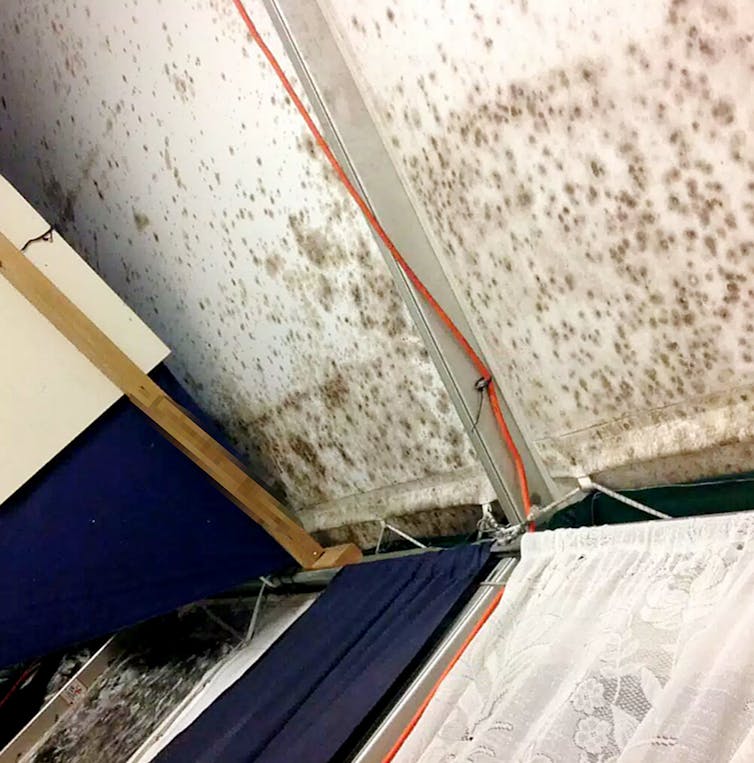

A series of recent reports by The Guardian have revealed refugees, asylum seekers and staff at the Nauru processing centre have been exposed to a mould problem of “epic proportions”.

The fungal growth in housing and working areas has reportedly led to some staff describing ongoing health effects including cognitive impairment and chronic lung infections. According to The Guardian:

At least a dozen former staff who have worked in the regional processing centre are understood to have developed conditions from exposure to mould and breathing the contaminated air in the buildings.

More than 300 refugees and asylum seekers, including 36 children, still live in mould-prone tents on Nauru, despite the government having been repeatedly warned of the health risks.

Assuming the photos and videos obtained by The Guardian accurately represent the extent of the problem – which looks quite extreme – it’s fair to assume there would be some negative health consequences, particularly in those who have allergies or a lower immunity. However, the association between cognitive impairment and mould exposure is a contested area of research.

Read more: Health Check: how does household mould affect your health?

Levels of mould

Mould accumulates in damp and poorly ventilated buildings. And enclosed rooms on a tropical island are particularly good environments for this sort of growth.

The Guardian reports tests carried out at Nauru, by microbiologist Dr Cameron Jones, indicated levels of mould around 60-70 times higher than normal range.

When conducting an investigation for mould growth and indoor air quality, the general rule is if there’s visible mould growth on surfaces, there’s a good chance there’s a problem. Large areas of visible mould tend to mean a bigger problem.

Areas of mould growth greater than one square metre of mould indicate a mid-level problem, and areas greater than 10 square metres a serious problem.

A common thing to look for is the number of airborne spores that the mould is producing. Microbiologists usually take samples from a non-problem area and outside, and then compare the number of spores to the mouldy room.

Such a test in a major city would probably find around 500 spores (known as colony forming units) per cubic metre of air outside, and less than half that inside buildings. This number is quite normal and likely to be up to double in summer and autumn, and sometimes half that in spring and winter.

So if your measurement is 10 or 100 times greater than those numbers, you probably have a serious problem.

The photos from Nauru suggest many areas greater than one square metre of fungal growth, and some areas greater than 10 square metres. This would likely mean the number of airborne spores is in the 10-100 times the normal range, maybe even 1,000 times higher.

Health impacts

Several factors play a part when determining what kind of risk such levels of mould exposure can pose to human health.

Spores in this concentration may cause allergy-type symptoms such as a runny nose, itchy eyes and skin, wheezing, sensitisation to other allergens, and general discomfort in exposed individuals.

Infection from these airborne spores (mycosis) is typically uncommon. It occurs mainly in those with compromised immune systems, such as people receiving chemotherapy, those who have received organ transplants, and those with autoimmune diseases.

However, the volatile and airborne compounds (mycotoxins) produced by certain species of mould, particularly from the genus Stachybotrys, and certain species of Aspergillus and Penicillium can be seriously harmful to human health. These can cause pulmonary (lung) haemorrhage (bleeding), increase the risk of cancer, suppress the immune system and airways and cause lung inflammation.

If these toxic species are present, even smaller areas of contamination are treated as a problem.

Read more: Hidden housemates: meet the moulds growing in your home

The Guardian has reported former staff indicating ongoing respiratory illness, fatigue and, in one case, cognitive disability. There is little research done when it comes to such conditions resulting from a fungal origin. The results are contentious and debated and unfortunately very hard to attribute to mycotoxin exposure.

It seems plausible that continued exposure, causing inflammation and pain in the face, neck and upper airway, combined with the likely effect of reduced sleep quality, could result in ongoing fatigue in workers and residents. This is a theoretical position though, and not based on any first-hand evidence.

It seems clear there’s a lot of mould growing at the Nauru processing facility. It also seems very likely staff and residents were in a position to be exposed to fungal spores and possibly any compounds produced by the mould present.

But working out who was exposed, for how long, in what concentration, to what spores, combined with each individual’s health status at the time, unique sensitivities and immune systems results, is a large ball of wool to untangle.

Attributing the cause of these health effects so long after exposure can make detection of mycotoxins, their breakdown products, or biomarkers, in exposed individuals very difficult.