Most of the young people who matriculate in South Africa and qualify on paper to apply to study further simply aren’t ready for the rigours of a university education. This isn’t a sweeping generalisation: it’s proved by data collected over five years as part of the country’s National Benchmark Test in Academic Literacy.

This test is not a replacement for the National Senior Certificate, or matric, examinations. Instead, it is complementary and designed to help the higher education sector better understand the needs of entry-level students who’ve come from a diverse range of schools.

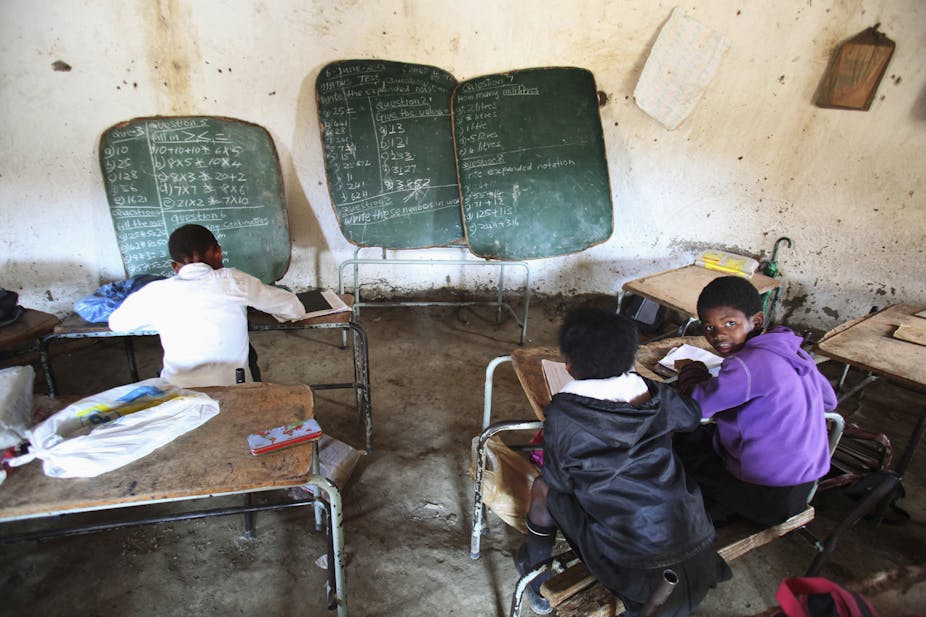

But this data is being misused by some in the higher education sector who complain that secondary schools aren’t producing young people who are academically literate. It is true that the primary and secondary education sectors are hugely troubled.

Does this mean, then, that universities should effectively wash their hands of these applicants, whom they say don’t “belong” in tertiary education?

The answer is no. There are far more positive, progressive ways for the National Benchmark Test data to be applied – in curricula, teaching and learning support. Before exploring these further, it’s necessary to examine what the latest round of testing tells us about South Africa’s university applicants.

What the data tells us

More than 70,000 applicants to higher education were tested in 2014. Only about one-third of them could be regarded as ready to cope with the typical reading, writing and reasoning demands they’ll face in tertiary study programmes. This echoes the results from previous years.

Here are some key figures from the 2014 National Benchmark Tests:

About 33% of applicants are ready to cope with the academic literacy demands they’ll face in tertiary courses;

More than 50% need extended or additional forms of academic support and provision if they are to succeed in higher education; and

Between 10 and 15% will struggle to cope with the demands of academic literacy if they don’t get ongoing, intensive and specific forms of academic support and provision.

The overall picture is slightly different if one looks at the breakdown of applicants by fields of study. For example, the proportion of applicants wishing to enter a Health Sciences, Engineering or Natural Sciences field of study who are deemed ready to cope is higher than 33%. This is quite simply because applicants who are interested in these fields tend to have higher levels of academic literacy.

It’s useful to consider what “academic readiness” means here. The definition is based on years of research about the entry-level reading, writing and reasoning demands that students ought to be able to cope with in the language of instruction in South African universities.

The test assesses students’ ability to:

- Make sense of what they read in academic texts;

- Separate main points of an argument from their supporting detail;

- Make inferences beyond text and reason analogously;

- Work out word and concept meanings from context; and,

- Link ideas within and across texts.

These are critical skills for any student in higher education, no matter the degree programme.

Universities can help

The National Benchmark Tests make it clear that many students will struggle to make the transition from secondary to tertiary study. If properly used, the data can enable the tertiary sector to move away from the act of blaming schools for not having prepared students sufficiently.

The test results offer excellent insight into who is trying to enter the university system and can support the placement of students in particular academic programmes. This information can also support the design and redesign of curricula to explicitly address the academic literacy demands that students will face. It can be used to develop forms of teaching and learning support to build students’ reading, writing and reasoning abilities.

We have a language of description here that can be utilised to start engaging with academics across all disciplines in addressing the fundamental literacies demands that students face. The ultimate goal is a better-prepared graduate body which can better contribute to national social and economic development.