If there’s one thing that could be observed from Fairfax’s move to publish its first tabloid-sized broadsheets it was a surprising level of neuro-illiteracy.

Fairfax’s head of advertising, Sarah Keith, has been quoted explaining why the company’s advertisers should not feel the move to a smaller size will hamper the impact of their advertising:

There was a concern that you think well maybe you’re using the left brain, [the] more detailed side of the brain when you read a broadsheet, but maybe with compact you’re just sort of skimming over things.

Actually what we discovered is that the brain was in a very, very balanced state when reading the compact, which was great news.

From my point of view when I’m going out to talk to advertisers [I’m] saying look, actually your ads are going to be more engaging in this product.

This quote is a prime example of how neuroscience can be so misunderstood and it provides an acute insight into society’s relationship, via the media, with neuroscience today.

The conclusion may be correct; but the argument leading up to it is neuro-nonsense. In this quote a scientific experiment has been laid out: there is a hypothesis, a result and a conclusion.

The proposal is that people may skim a tabloid-sized newspaper and, by not concentrating on detail, they will not use the left side of the brain.

To say that one whole half of the brain disengages when less attention is devoted to detail is a flight of fancy. There are, however, the beginnings of a reasonable hypothesis in this idea.

It’s possible to say that, in general, the left hemisphere is more involved in language than the right. But this has almost nothing to do with folk neuroscience understanding of the “left brain” being details-oriented.

When it comes to understanding how the brain is involved in feeling “engaged” by a newspaper, the left brain/right brain distinction is essentially nonsense.

The second sentence implies that an experiment was carried out and a very, very balanced state was the result. This may sound reassuring but in reality this result is essentially meaningless, particularly given the hypothesis that the whole left brain may be less active when reading the compact paper.

The likely actual result is a similar pattern of activation across corresponding regions in the two hemispheres, and that this doesn’t change with the size of the paper.

This is a reasonable result but can we truly discern from this whether broadsheet and tabloid-sized newspapers are equally engaging? If all you wanted to show was that people bother to look at the contents of the compact newspaper then there is no need to carry out neuroimaging at all. Eye-tracking alone would tell you this.

If the intention was a more sophisticated understanding of the difference between types of engagement (assuming both sizes are engaging but in different ways) there are clear problems.

On its own, any neuroimaging measure available today would lack the resolution to provide a pattern of data easily interpretable as something as complicated as difference in engagement. Such findings would be experimental rather than applied.

As for the assertion that a balanced brain is a sign of higher engagement, we’re still a long way from predicting real world outcomes using neuroimaging techniques.

Giving Sarah Keith the benefit of the doubt, she may have been unprepared to accurately convey the neuromarketing findings and her quote is quite obviously missing some crucial context.

In that case it’s up to the media outlets publishing the quote to smell a fish and choose what to do with it.

New-age neuro

The media is not alone in being caught up unthinkingly in the new age of the neuro. The serious advances made by scientists are being over-interpreted in an increasing number of ways.

Outside of companies paying for neuromarketing studies, the use of neuroimaging evidence in court is pushing our knowledge too far. Can we infer whether a person could have acted with intention from a brain scan?

There is no evidence we can do this with any better reliability than from examining that person’s behaviour. Yet neuroimaging sounds more scientific and therefore more reliable than behavioural observations.

Images of brains have been found to be very persuasive. Sarah Keith’s reliance on neuroscience to convince advertisers is a prime example of this in action. Admission of neuroevidence in court is becoming a real concern in the USA.

While Australia can claim some moral high ground, that’s possible it’s only because we are a couple of steps behind.

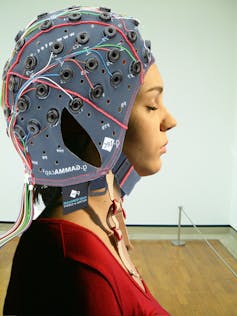

Wired up

Less obvious and more pervasive are the beliefs that people who are not like us have brains that are just wired up differently, forming a persuasive, pseudoscientific justification of discrimination.

Could the persistent idea that “girls just aren’t good at maths” be justified by showing that a splodge of brain looks less active when a cohort of girls tackles a math problem compared to a cohort of boys?

Less activation in a region of the brain, as measured via neuroimaging, may actually represent an enhanced ability of when a practiced skill becomes more effortless.

There can be several plausible explanations for apparently reduced activity. Simply put, neuroscience is not yet an area of science that can be used with confidence in a way that it will impact directly on our day-to-day lives.

While I’ve been focusing on human neuroimaging, all of neuroscience suffers from the same fate of being over-interpreted in the world beyond the laboratory.

Neuroscience has made impressive and substantial recent advances, but the appetite for all things neuro is outpacing the real-world applications of the lab science.

What I hope is that alongside society’s interest in what goes on in the labs of neuroscientists, there is also an increased level of neuroliteracy, a healthy dose of neuroscepticism and an understanding that the truth in the science can be stretched much too far.

In particular, when you’re interested in how engaging a newspaper is you don’t need neuromarketing to peer inside a brain – it is still more reliable (and often cheaper) to just ask the person.