Barack Obama, the US president, waxed lyrical about some of his administration’s remarkable foreign policy achievements in his recent speech to the Democratic National Convention. “Through diplomacy, we shut down Iran’s nuclear weapons programme,” he said. “We opened up a new chapter with the people of Cuba, brought nearly 200 nations together around a climate agreement that could save this planet for our children.”

But while Obama drove home a powerful and personalised message about the appeal of American values, he said next to nothing about his attitude to one of the US’s most established priorities: the often-controversial business of promoting democracy around the world.

This highlights the fact that his administration has tended to prioritise short-term US national security interests over supporting democracy. Back in 2010, the Obama administration issued a National Security Strategy in which it set out its approach to promoting democracy.

As it explained, the administration’s vision had two main elements. The first was combining engagement with dictatorships with “top-down” pressure on them to open up political space in their countries. The second was “bottom-up” engagement and aid to overseas civil society groups to foster democratisation.

Clearly the administration believed that promoting democracy would strengthen the US’s national security by creating more stable societies overseas. But this “double engagement” approach also raised the awkward question of whether working with dictatorships to ensure short-term security could be reconciled with the mission to foster political change in the interests of longer-term security.

In the end, the administration seems to have prioritised short-term US national security – and that has undermined both its top-down and bottom-up approaches.

The administration’s response to the “Arab Spring” in 2011 shows the complications of the top-down approach. In Egypt, the administration pressured the country’s authoritarian president, Hosni Mubarak, to step down. Although Mubarak was a key ally against Hamas and Iran, mass protests showed that he could no longer wield effective authority, so Washington gambled on pushing for a transition to democracy, the end goal being a stable government with popular support.

In contrast, Obama made little noise when pro-democracy protests in Bahrain were suppressed by regime security forces and Saudi troops. Preserving access to naval bases in the country for the US Navy’s Fifth Fleet, it seems, took precedence.

When the democratic Islamist government Egypt elected to replace Mubarak was also overthrown in a coup led by General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi in 2013, the administration did not strongly criticise it. It also accepted Sisi’s flawed presidential election victory in 2014.

For Obama, security co-operation with a friendly and stable Egypt had become more important than democracy. Congress imposed aid restrictions to try to moderate the regime’s repression, but the administration has been more concerned by Sisi’s more independent foreign policy than his dictatorial style of rule. In each case, the administration followed the policy it deemed most compatible with existing US national security interests – and this has often meant supporting dictatorships rather than pressing them towards reform.

Reined in

The administration has also backed away from the bottom-up funding of civil society groups overseas. This process has been spurred by the need to work closely with conservative Arab states to combat IS.

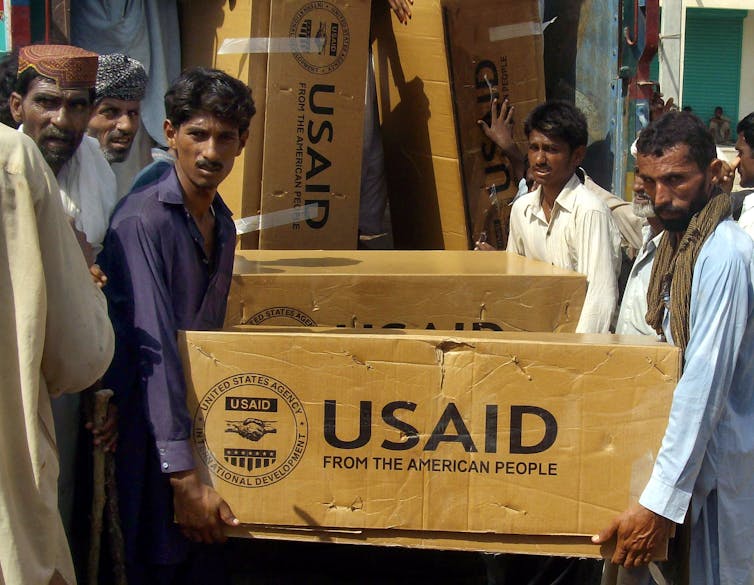

So far, this imperative hasn’t undercut funding for US government agencies that aid foreign civil society groups, such as the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI). But even if their budgets haven’t been slashed, these organisations’ prerogative to fund independent foreign democratic groups has been threatened.

MEPI, which was set up as an independent government agency in 2002, has been placed more closely under the authority of the State Department. This makes it more likely that the funding of politically contentious foreign groups will be reined in, so as not to undermine the department’s core mission of maintaining diplomatic relations with foreign states – including dictatorships.

USAID is under pressure, too. The administration has tried to weaken legislation that bars foreign governments from influencing which civil society groups receive democracy-promotion funding from USAID, meaning that dictatorial allies could lobby the US government to cut funding to democratic groups they perceive as threatening to their rule.

In the worst case scenario, such changes would make the US “democracy bureaucracy” less likely to fund organisations that may upset such allies.

Pragmatism forever?

It’s difficult to predict precisely how Hillary Clinton will approach democracy promotion should she be elected president. Her nomination speech at this year’s Democratic convention offered few clues, so her tenure as Obama’s secretary of state is the best indication – and on that basis, there seems to be little daylight between Obama and his prospective successor.

In a 2011 speech on the Arab Spring, Clinton affirmed the US’s support for democracy as an element of national security strategy, but cautioned that “there will be times when not all of our interests align … that is just reality”.

She also acknowledged that the US’s attitude to different pro-democracy movements abroad doesn’t always look consistent from the outside. Nonetheless, if she holds this line, she’s likely to follow Obama’s lead in prioritising national security over democracy promotion when the two priorities conflict. This doesn’t reflect some deep personality flaw in either her or her predecessor; it’s a pragmatic response to the challenges of an unstable and often uncooperative world.

After all, the US is less powerful in general than it has been in some time, and its leverage over undemocratic regimes has been weakened as alternative backers such as Russia and China enter the fray. It’s hardly surprising that it’s making some striking compromises to try and keep its footing.