On November 24, a grand jury in Ferguson, Missouri declined to indict white police officer Darren Wilson for fatally shooting an unarmed black teenager in August 2014. Although the outcome was hardly a surprise, it nonetheless appalled and outraged a community that had been waiting, watching and participating in this drama for months.

Pleas for calm from the family of the deceased Michael Brown chimed with a similar message from president Obama: both have been ignored. Ferguson has seen its worst night of rioting yet, with an outbreak reported in Oakland, California. Protests have also spread across the US.

The grand jury met 25 times, and heard from 60 witnesses before deciding that there was not the “probable cause” necessary to say that Wilson had committed a crime. One Ferguson resident said on hearing the verdict that surely “it couldn’t be this unjust.”

But even if this decision was just, it is merely the latest brief paragraph in America’s deeply fraught racial narrative.

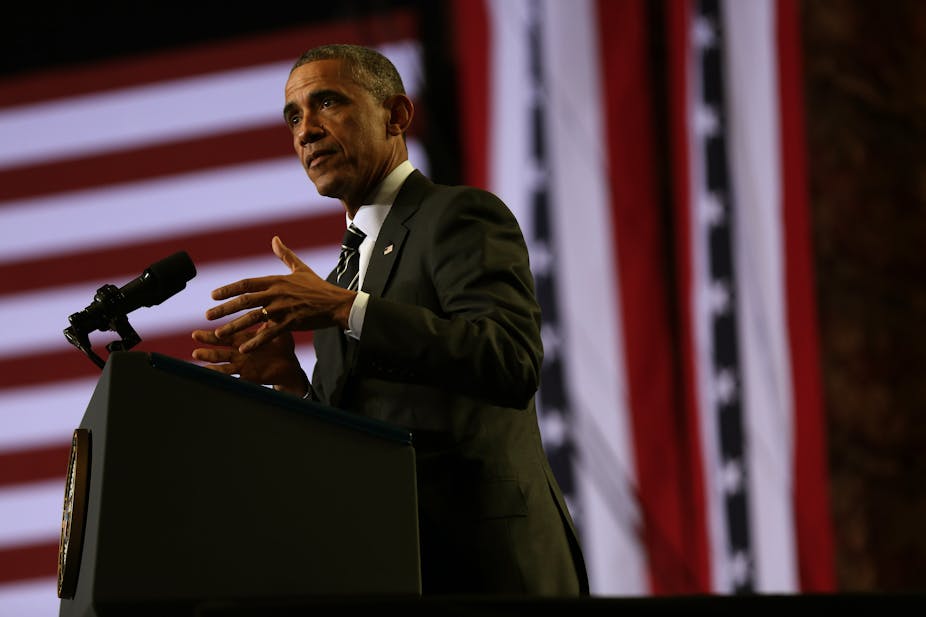

In his televised speech to the nation after the grand jury ruling was announced, Obama spoke of the progress made within his lifetime – in particular, the hope and once-unimaginable change offered by the civil rights movement. But he also reminded his audience that the often violent relationship between law enforcement and minorities, and the urgent need for criminal justice reform, are issues not just for Ferguson, but for the whole of America.

For anyone looking for a metric of progress in the past generation, and a measure of Obama’s response to the crisis, a good starting point would be the address made by president George HW Bush in response to the 1992 LA race riots.

History repeating

In April that year, a Los Angeles jury returned a not guilty verdict on four policemen who were accused of beating an unarmed black man named Rodney King. The verdict was met with outrage, as the beating had been caught on camera. African Americans saw the verdict as a prime example of unequal justice for urban blacks and suburban whites; rioting erupted in South Central LA.

The rioting was so intense that Bush sent in the army to restore order. When the dust settled, there were 47 fatalities, 2,100 injured, 9,000 arrests, 5,000 buildings damaged and US$500m in insurance costs.

In his televised address, Bush said the riots were “not about civil rights” but about “the brutality of the mob, pure and simple.” A textbook patrician conservative, Bush took refuge in moral condemnation of the rioters as looters and criminals, rather than making any effort to reflect on the root causes of such events.

The tone and content of Obama’s address after the verdict was measured and constructive, and a far more emotionally intelligent response to the protests and riots than his predecessor a generation earlier.

But the first African American president has an impossible line to walk with regard to matters of race. Anyone who has read his memoir, Dreams from my Father, knows he has personally felt the challenges of being a non-white citizen. And yet, during his 2008 campaign, he was often described as a “post-racial” candidate, and was under enormous pressure to conform to that image. Recall how he was obliged to swiftly distance himself from his erstwhile mentor, the left-wing Reverend Jeremiah Wright, who had once dared to preach the words “God Damn America!” – which he did with a remarkably eloquent and temperate address, “A More Perfect Union”.

Throughout Obama’s six years in office, conservative opponents and pundits have been waiting to pounce the moment the president might sound like that most fearsome entity in America: the Angry Black Man. And, to the frustration of so many black citizens, he never has – despite myriad incidents that could well have fired his rage.

True justice

In America, the deaths of young black men at the hands of white police officers occur with chilling regularity. But Obama simply cannot be heard to condone civil unrest – even if, in the words of Martin Luther King, “riots are the language of the unheard.”

And yet, as he enters the final quarter of his presidency, the “lame duck” period where he is liberated from the constraints of re-election, his eye will surely stray towards the thorny issue of legacy, particularly in relation to racial justice.

The tenure of the former attorney general, Eric Holder, provided a robustly positive record for the administration on this front. In addition, material benefits are already starting to help poorer communities: raised minimum wages for federal contracts and the implementation of Obamacare, however uneven, are major steps forward.

Still, as far as real racial justice goes, it’s the US’s criminal justice system that urgently needs attention and reform. The imprisonment rate for black Americans is still radically higher than for white Americans, and the damage that this does is immense.

Clearly, the pragmatism and the moderation required for Obama’s political survival have so far taken priority, and he has had to hide the full force of his anger about the injustices so many of his fellow Americans suffer on a daily basis simply because of their race. Now he has the freedom of being a lame duck, the post-Ferguson chaos might push him to change his tone.

In the meantime, the lofty rhetoric of the original Obama campaign seem like a half-forgotten dream. As Obama himself knows all too well, the US has never been a post-racial country.