“On the night of 27–28 November 1989,” Stejărel Olaru writes, “seven people hurriedly but warily made their way towards the frontier between Romania and Hungary.”

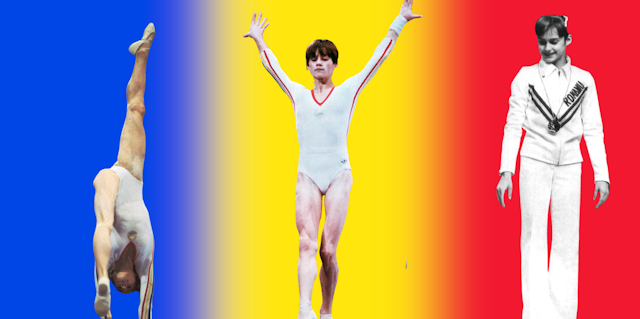

Five-time Olympic gold-medal-winning Romanian gymnast Nadia Comăneci was one of those scrambling across fields in the dark.

Review: Nadia Comăneci and the Secret Police: A Cold War Escape – Stejărel Olaru, translated by Alistair Ian Blyth (Bloomsbury)

“By now it was after midnight and the temperature had dropped so low that the cold had become a real danger,” Olaru adds:

although it wasn’t the only one, nor even the most significant, since the seven had embarked on the perilous adventure of their lives: they were about to make an illegal border crossing between two communist states.

These quotes, which would sit comfortably in a Le Carre thriller, come from Nadia Comăneci and the Secret Police: A Cold War Escape (2023).

Translated from Romanian by Alistair Ian Blyth, this book sheds light on state surveillance, lived experience and sport in the Eastern Bloc.

The most famous gymnast in the world

To say Comăneci was well-known when she fled Romania would be an understatement.

Put simply, Comăneci, the first gymnast to be awarded a perfect score of ten in an Olympic event, was, as Olaru points out, “the most famous gymnast in the world”.

Comăneci was born on November 12 1961 in Onęsti, a provincial town in the Carpathian Mountains. She displayed an interest in gymnastics at an early age.

Her parents approved, hoping Nadia would burn off excess energy. Olaru notes that the precocious youngster “began to learn exercises on the mat, the vault, the parallel bars, and the beam, doing things she wouldn’t be able to do at home”.

All this, it should be added, happened while she was still in nursery.

By the autumn of 1969, Comăneci had enrolled at her local gymnastics centre, where she received formal training. In 1970, she became the youngest gymnast to win at the Romanian Nationals. Success after success followed.

Comăneci shot to international prominence in 1975 when, at the age of 13, she dominated proceedings at the European Gymnastics Championships.

“Nadia astonished not only the public,” Olaru asserts, “but also the opposing teams, who discovered a gymnast who, perfectly and unhesitatingly, could execute exercises of extreme difficulty.”

Comăneci’s performance had profound ramifications. In Olaru’s estimation, she single-handedly “managed to change public perceptions of the sport thanks to the perfection with which she performed her routines”.

Having piqued the world’s interest, Comăneci reached the pinnacle of gymnastic perfection at the 1976 Montreal Olympics, when she scored her famous perfect ten on the uneven bars.

Olaru’s description of Comăneci’s remarkable routine is worth quoting:

Nadia leapt straight to a support position on the high bar and cast away from it to perform a straddled front somersault while re-grasping the same bar. Her routine was marked by moments of exquisite balance as she performed handstands and her well-known full twisting somersaults between bars. Finally, using the spring of the lower bar for lift, she span through the air before sticking a perfect landing. The whole routine had lasted a mere twenty seconds.

The arena erupted in applause. Comăneci’s name and score was on everybody’s lips and immediately started to wend their way around the world.

This performance transformed gymnastics and changed Comăneci’s life. She received a hero’s welcome on returning home. Her name and likeness adorned posters all over Romania.

Never one to miss a publicity opportunity, Nicolae Ceaușescu – Romania’s dictatorial ruler – also looked to get in on the action. He declared Comăneci an official Hero of Socialist Labour.

In the same breath, Ceaușescu moved to safeguard what he regarded as a national asset and propaganda tool – a device that might prove useful when stoking mass patriotic sentiment. This explains why, over the coming years, Comăneci and those close to her were subjected to sustained state surveillance.

Compounding matters, in 1985, the Ceaușescu regime refused to let Comăneci – who was by then working as a sports ambassador – travel abroad, except to other communist countries.

This, in turn, accounted for Comăneci’s decision to leave Romania in 1989. She simply couldn’t stand the pressure and intrusion any more.

“All the restrictions in her life convinced her that she should abandon caution and do something that was not in her nature,” Olaru surmises, even if that life-threatening decision to set out to the United States likely meant she would never see her family and loved ones again.

Such is the dramatic personal narrative that Olaru puts forward in his book, which makes impressive use of 25,000 pages’ worth of secret police documentation, state intelligence archives and extensive wiretap recordings.

This, though, is but one part of a larger and more distressing story.

Influential, abusive coaches

I mentioned before that Comăneci and those close to her were, in the wake of her triumph in Montreal, subject to remarkable, even intolerable levels of state-sanctioned scrutiny.

This applied, too, to the married couple who trained Comăneci from a young age.

Béla and Márta Károlyi are two of the most influential and successful coaches in the history of gymnastics. They are also extremely controversial - as viewers of Athlete A will already know.

Consider what Olaru has to say about the pair, who feature prominently in every chapter of his book. (In fact, there are moments when one could be forgiven for thinking Olaru is really interested in writing about the Károlyis and the secret police.) A word of warning though: this is confronting material.

“Today,” Olaru remarks, “it is no secret that the Károlyis used to beat their gymnasts.”

Indeed, “Béla Károlyi’s hand was so heavy that the victim of his abuse, a defenceless child, would be knocked over, bowled across the floor.”

Olaru makes the point – and the archival record supports him – that the abuse Comăneci and her peers suffered at the hands of Bela Károlyi was not only physical:

Repeated blows, verbal violence and insults, starvation, excessive and aberrant control of medical care, and the inhuman demand to train and compete even when injured caused deep wounds in the psyches of the gymnasts, who distanced themselves from him, regarding him as cruel, and certainly not as a protective father figure. Only when there was a need to manipulate them did he tell the young gymnasts he cared about them.

How, we might ask, did Károlyi get away with such appalling behaviour?

The depressing conclusion Oralu reaches is that the Romanian authorities chose to ignore the multiple warnings that came their way. Officials at the very “highest level” were more than happy to support Károlyi, provided he kept on winning.

And this he did, up until the moment – in March 1981 – when he and Márta defected to the US.

Having traded communism for capitalism, the Károlyis set about re-establishing themselves as trainers in their adopted state of Texas. US gymnasts were keen to work with the man who had played such an important role in Comăneci’s career.

Károlyi’s first major success in the US came as the coach of Mary Lou Retton, who won a gold medal at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, becoming the first US woman to win the all-round gold medal in Olympic gymnastics.

This achievement caught the attention of USA Gymnastics. Béla Károlyi went on to serve as a member of the US Olympic coaching staff at four more Olympic Games, and worked as National Team Coordinator until 2001 (when Márta Károlyi took over).

Read more: Girls no more: why elite gymnastics competition for women should start at 18

America’s gymnastics community knew

Given Béla Károlyi’s success in the US warrants barely a mention in Oralu’s study (which takes leave of the Károlyis not long after they make their break for the West), one could be forgiven for asking if any of this matters.

It matters because it’s clear the US gymnastics community was well aware of Károlyi’s reputation.

Take Joan Ryan’s Little Girls in Pretty Boxes, published in 1995, which exposed the abusive reality of professional gymnastics in the US.

Given what we have already established, it will come as no surprise to discover Béla Károlyi and his methods came under sustained attack in Ryan’s searing exposé.

But nothing happened. USA Gymnastics continued to place its trust - and the bodies of its athletes - in Károlyi’s hands.

The impression we are left with is the same one we get when reading Oralu: it seems some people are significantly more interested in the pursuit of gymnastic success than in the physical and mental health of the gymnasts themselves.

Troublingly, as the Károlyis’ involvement in the devastating USA Gymnastics sex abuse scandal of recent years demonstrates, it appears not much has changed since the days of Comăneci and the Iron Curtain.