Review: Unfinished Business: The art of Gordon Bennett, QAGOMA, Brisbane.

At the entrance to this exhibition, there is an excerpt from the artist’s notebook from December 1991. Written just three years after Bennett graduated from art school as a mature aged student, it gives a very clear sense of his early ambition and political purpose.

He writes:

I am trying to paint the one painting that will change the world before which even the most rabid racists will fall to their knees … of course this is in itself stupid and I am a fool but I think to myself what have I got to lose by trying?

Impossible aims, such as this one, often underpin and drive the work of major artists; an achievable aim after all would be quickly satisfied. A cause as worthy and challenging as anti-racism, on the other hand, can provide material for a lifetime. This task is the “unfinished business” referenced in the title of the show.

Bennett died in 2014, aged 58. He did not discover his Aboriginal heritage until around age 11 and always resisted being pigeonholed as an Aboriginal artist. Given that consistently expressed view, thinking about how his work addresses the cause of anti-racism is an apt prism through which to view the current exhibition.

Certainly, the notebook quote reflects how Bennett’s reputation has been cemented in Australian art history. We tend to think of him as a key figure in political or critical postmodernism.

Read more: Explainer: what is postmodernism?

He is understood alongside politically inclined American artists from the so-called Pictures generation of the 1970s and 80s (Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levin). In Australia, he would be placed in dialogue with key postmodernist artists such as Imants Tillers, Tracey Moffatt, and Juan Davila.

Of the latter four, Bennett is most easily understood as a critical postmodernist. Typically, this is the style of contemporary art associated with ideology critique, unveiling systems of discrimination and oppression like racism and sexism. This critical orientation is particularly evident in Bennett’s history paintings, displayed in the third room of the exhibition.

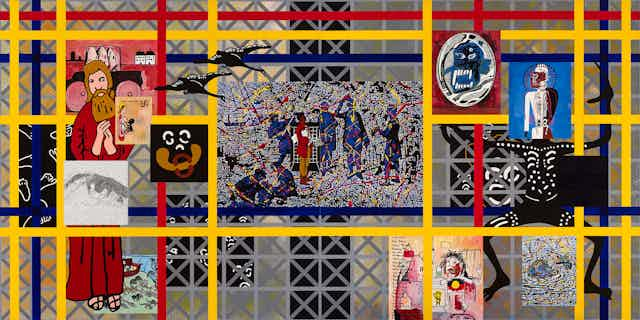

These large scale history paintings of the 1990s are perhaps his best known works. They often use the dots associated with Aboriginal Western Desert painting intertwined with western systems of realist depiction.

The visually complex and layered works challenge received accounts of Australian colonial history. They reference the massacres of Aboriginal people — in Myth of the Western man (White man’s burden) (1992) and The nine ricochets (Fall down black fella, Jump up white fella (1990) — and question the valorising of Captain Cook in Big Romantic Painting (Apotheosis of Captain Cook) (1993) and Possession Island (1991).

In his recent book Rattling Spears: A History of Indigenous Australian Art (2016), art historian Ian McLean argues that anger is the consistent emotion expressed by Bennett’s work. He writes of Bennett: “The anger is never far from the surface of his work, though he was perplexed by the common perception of it as angry.”

Perhaps McLean reads Bennett’s work in this way because anger at injustice is the emotional tone critical postmodernism typically adopts. But is this the tone Bennett actually adopts? I confess I used to think so, but seeing this exhibition has made me reconsider.

Form as much as content

In Bennett’s most anthologised article, acerbically titled “The Manifest Toe”, he describes his approach to art using an expression that is often used in critical rather than art theory: the “politics of representation.” Here we get to the crux of Bennett’s contribution. Not only is art about political content, form is also at stake. Representation itself is political.

Attending to form as much as content enables a different view of Bennett’s oeuvre and critical purpose. Indeed, Bennett’s extraordinary attention to visual languages, their meanings and implications, is the key revelation about his oeuvre I have taken away from the current exhibition.

I already knew Bennett was in dialogue with other artists and their distinct painterly idioms: Mondrian, Margaret Preston, Thomas Bock, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jackson Pollock to name just a few. I was also aware of his concern with western systems of representation and their oppressive effects.

What I had not realised is that he is also in an intense dialogue with himself and his earlier work. Looking through the exhibition, this internal language becomes insistently present as the resonances between works start to sound.

Forms and styles of representation recur, transmute and metamorphose across his oeuvre in a dizzying fashion.

For example, the small painting of a black angel in the installation in the first room of the exhibition titled Psycho(d)rama (1990) recurs in Notes to Basquiat (Jackson Pollock and his Other) (2001).

Read more: 'Nothing quite prepares you for the impact of this exhibition': Haring Basquiat at the NGV

The strange row of heads depicted in the very early work, The Coming of the Light (1987) forms part of the background of this same image.

Pollock’s vibrant skeins of paint can be tracked across a range of works: a section of Blue Poles as a background image in Notes to Basquiat (Jackson Pollock and his Other) (2001).

Read more: Here's looking at: Blue poles by Jackson Pollock

Pollock’s action painting is presented as a form of cultural appropriation of First Nations’ sand painting in Notes to Basquiat: Bird (2001), and those same active lines form the veins of Bloodlines (1993).

The diversity of Bennett’s work is another striking feature. At times it is as though we are looking at the work of more than one artist. For example, expressionism features in the highly visceral Outsider (1988), which replays Van Gogh’s Starry Night. An Aboriginal man is inserted into the picture whose exploding head is turning into stars.

In Notes to Basquiat (Death of irony) 2002, Bennett astonishingly knits a homage to Basquiat with Islamic patterns and calligraphy into a coherent composition .

This is the third major survey show to consider the breadth of Bennett’s work and should not be missed. Bennett emerges as one of the most important Australian artists of the latter part of the 20th century and one we have certainly not finished interpreting.

Unfinished Business can be seen until 21 March 2021.