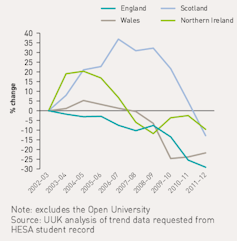

Part-time higher education in the UK is contracting dramatically. The decline in numbers is critical, especially in England, where there were 47% fewer part-time students in 2013-14 than there were in 2010. In my recent research, surveying part-time students who have hung on, I found they feel sidelined by their institutions and are crying out for more flexibility to cope with their studies.

The crisis in part-time higher education is predominantly, but not exclusively, an English problem, set against changes to fee structures that have resulted in part-time fees tripling since 2012, and no maintenance grants for part-time study.

The sub-degree market – those certificates, diplomas and awards of institutional credit which offer a less intensive higher education alternative for those mature students unable to commit to a full-time degree – has experienced the steepest decline, of 55%. Foundation degree numbers – those innovative courses offering vocational and applied routes into higher education for students with non-traditional entry qualifications – have dropped by 18%.

All this as applications for full-time higher education are buoyant, recovering from a dip in 2012.

The fall in the Celtic nations is less pronounced, although Wales has experienced a 24% drop in the last five years despite a commitment from the Welsh Assembly to widen access for those with “protected characteristics”. Scotland also saw a 7% drop from 2013-14 while numbers in Northern Ireland have dropped by 5% in the same period.

Barriers for part-time students

My research for the Higher Education Academy looked at the experiences of part-time higher education learners across the UK, based on 3,000 survey responses and 50 phone interviews.

This is a very diverse, heterogeneous group, studying part-time due to a wide range of personal circumstances and competing work commitments. Most are women, often juggling caring responsibilities alongside studying. Many were the first in their families to embark on higher education, and 22% reported disabilities or long-term health impairments. Many respondents managing mental health problems, medication, hospital visits and declining mobility viewed part-time study as a lifeline.

Only 15% reported getting support from their employers for their studies. Almost all admitted they would prefer to be studying full-time, feeling they had missed out. But they could not imagine being able to afford to study without working. They needed flexibility to meet their learning circumstances, they were debt-averse, and they made calculations that the investment of time and money would translate into some personal transformation, whether in aspirations for a better job or the kind of lifestyle they desired.

Side-lined and shoe-horned

Any notion of students “choosing” to study part-time were seen as a meaningless illusion. Learners were faced with a Hobson’s choice in which there is only really one option: it was either part-time or nothing, since the costs associated with full-time were too great, and students feared the perceived inflexibility of full-time higher education. Two key motivations for studying part-time emerged from the research – improving employment prospects, followed closely by those who identified themselves as grabbing a second chance, having missed out at age 18.

Individual students were desperate for greater flexibility to enable them to cope with their studies. Over a third reported missing a formal element of their course due to personal and work demands. They bemoaned feeling part-timers were an “inconvenience” in their institutions, “side-lined” and “shoe-horned” into existing full-time structures.

They took employability seriously, but on their own terms. They wanted to develop skills and confidence to get a job or improve their job prospects, but in a highly personalised way, not represented by diktats aimed at 21-year-olds aspiring for graduate careers. They often did not identify themselves as “students”, nor did they feel part of a student community, and felt isolated from institutional support structures provided for full-timers.

They did not engage with the plethora of information, advice and guidance aimed at 18 year olds, and as a consequence they were often ignorant of qualification pathways, course workload or even sources of financial support. All this varied by disciplines, with some courses appearing to offer very different part-time student experiences.

Not all students are the same

Part-time higher education has a crucial role to play in social mobility. Opportunities to study part-time are at the forefront of widening access to the most disadvantaged adults, those vulnerable non-traditional students attempting a tentative first step into higher education. Part-time study has a positive affect on the economy, with mature students (the vast majority of whom are in full-time employment) seeking better careers in a global economy.

So any diminution of part-time opportunity affects precisely those groups that policies aimed at increasing social mobility are meant to address. But by their very nature, part-time students are a hard-to-reach group, and their needs are drowned out by a policy myopia which is ideologically infatuated with full-time higher education for 18 year olds paying high fees.

If the part-time sector is not to be inadvertently left to wither away, politicians need to create incentives for universities and colleges to prioritise part-time higher education as an attractive choice to meet the needs of the most disadvantaged students.

In order to create a flourishing education culture, universities and colleges need to listen more to part-timers. They should offer them the flexibility they need, recognise their learning priorities will be different, and celebrate their contribution to a more diverse student body.