This week, two of the original members of Australia’s 1971 “ping-pong diplomacy” team are returning to Beijing to mark the 50th anniversary of diplomatic relations between the two nations.

Half a century ago, few could foresee that a spur-of-the-moment, unscheduled visit by a young Australian sports team would lead to one of Australia’s most important – and sometimes turbulent – bilateral relations.

Only weeks after the team’s headline-making tour, Australia’s then opposition leader, Gough Whitlam, led a delegation to Beijing promising to open diplomatic relations “when elected”.

Whitlam delivered on that promise in 1972. Three weeks after taking office as Australia’s 21st prime minister, his government reached an agreement with the People’s Republic of China on the establishment of diplomatic relations. The following year, Australia’s first embassy in Beijing opened with the appointment of Stephen FitzGerald as the first ambassador.

As FitzGerald recounted on my podcast, The Ticket, this week:

The Chinese have a big love of sport, as do Australians. At one stage they used to talk about the three great balls. One was table tennis, one was basketball and one was volleyball.

‘A crowd of 8,000 people’

The 1971 ping-pong tour wasn’t the first time sport was used as a diplomatic tool, but it was perhaps one of the most successful of the Cold War period, with long-term benefits.

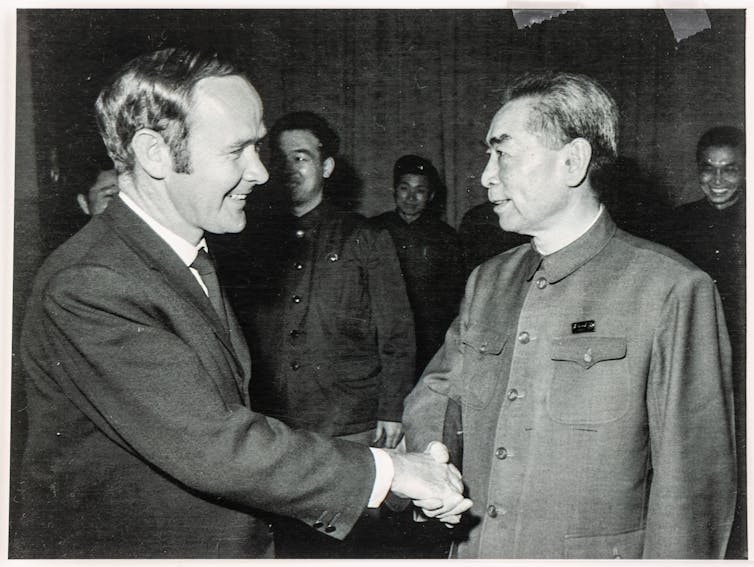

After competing in the Table Tennis World Championships in Japan in late March 1971, Australian and American table tennis players were invited to travel to China by the country’s first premier, Zhou Enlai. A revolutionary who became one of China’s most revered statesmen, he advocated peaceful co-existence with the West and other nations.

The American team embarked on their tour first – setting the stage for then-President Richard Nixon’s famous visit to Beijing in 1972. The Australians made their trip to China a couple weeks later.

Read more: 50 years after Gough Whitlam established diplomatic relations with China, what has changed?

Paul Pinkewich had just turned 20 at the time of the visit, teammate Steve Knapp was only 18. Now in their 70s, they will return to Beijing for a function at the Australian embassy today and share a meal with some of the Chinese players they competed against.

Pinkewich is taking his table tennis paddle with him in case he can get in a few matches with his old rivals.

“We had three great matches in China. You know, we’re used to 20 to 50 people in Australia watching tournaments. Our first match in Canton, now Guangzhou, I think it was a crowd of 8,000 people,” he recalls.

“There’s this one table in the stadium and we went out there, we actually had a win. We won 5-4. It was fantastic.

"I think friendship was more important than competition.”

The Australians suffered a narrow defeat in the second match in Shanghai. The third and final match was played in the Chinese capital. At the May Day celebrations that followed, the team was invited to the Great Hall of the People to meet Zhou.

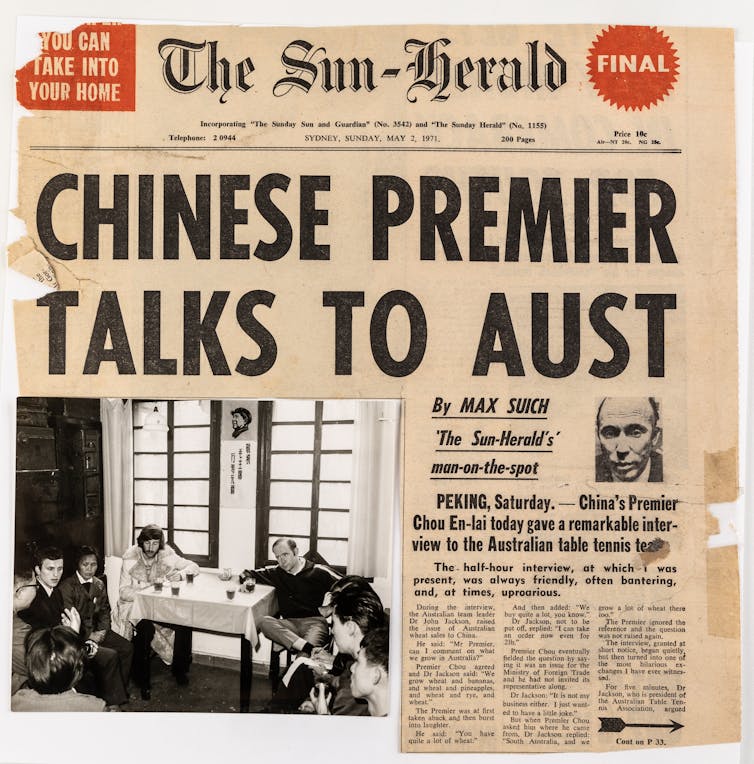

According to the Sun-Herald report from the journalist travelling with the team, the premier asked Knapp about his long hair and sideburns.

“Do you wear this hair because of your disagreement with society or because it is a style?”

Knapp replied, “It is the fashion.”

Pinkewich says he will never forget the sound of the crowds during the tour.

“Can you believe, one table in the middle of the Capital Stadium [in Beijing] with 18,000 spectators, and that was just an amazing experience. We got trounced 8-1 that night. But they always let the woman win.”

That woman was Anne Middleton, the other player on the 1971 tour, who has since passed away.

Leading the delegation were the then-president of Table Tennis Australia, John Jackson, who is now deceased, and coach Noel Shorter, who at 85 is not making this week’s commemorative trip.

Shorter remembers getting everything packed up from their coaching clinic in Tokyo with only four hours’ notice after being told there had been a change of plans and the team was heading later that day to China.

“At that time the [Australian] government was quite racial, as far as the Chinese were concerned, and they didn’t show any interest at all,” Shorter recalls.

“It’s funny. After the trip we were labelled as communists […] but we were interested in friendship first, competition second.”

Why sport diplomacy matters

Beijing has continued to use sport as a diplomatic tool, including becoming the first city in the world to host both a summer and winter Olympic Games (Beijing in 2008 and 2022).

French educator Baron Pierre de Coubertin founded the International Olympic Committee in 1894, believing Olympics were a global event. “All people must be allowed in, without debate,” he said.

That ethos is facing major challenges today as a new global rift emerges between the West and autocratic regimes like Russia, China and others. A new term has also emerged in recent years – almost always applied by researchers in democratic nations – to describe undemocratic nations’ forays into global sport: sportswashing.

Viewed through today’s lens, China’s invitation to the Australian team five decades ago would most likely be reported as an attempt by the Communist Party to use sport to wash its image.

But without that young Australian sports team breaking down barriers by travelling to China, who knows how different Australia’s current economic and cultural landscape would be?

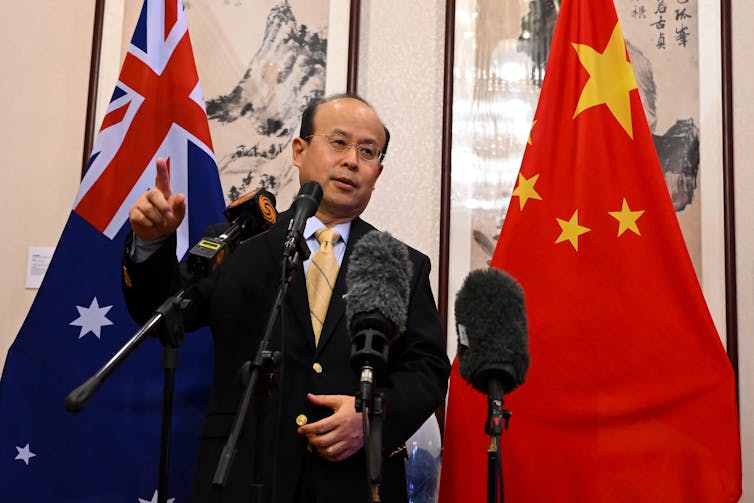

China’s current ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, has described the relationship between the two nations as “half a century of storms and sunshine”.

His comments are included in a book published by the Chinese embassy, titled Fifty People Fifty Stories. It details the experiences of dozens of Australians who have at one time lived and worked in Beijing.

“The relationship between China and Australia has become more mature, stable and resilient,” Xiao writes. “Amity between people holds the key to sound relations between countries.”

At the heart of such amity, sport continues to play a significant role.