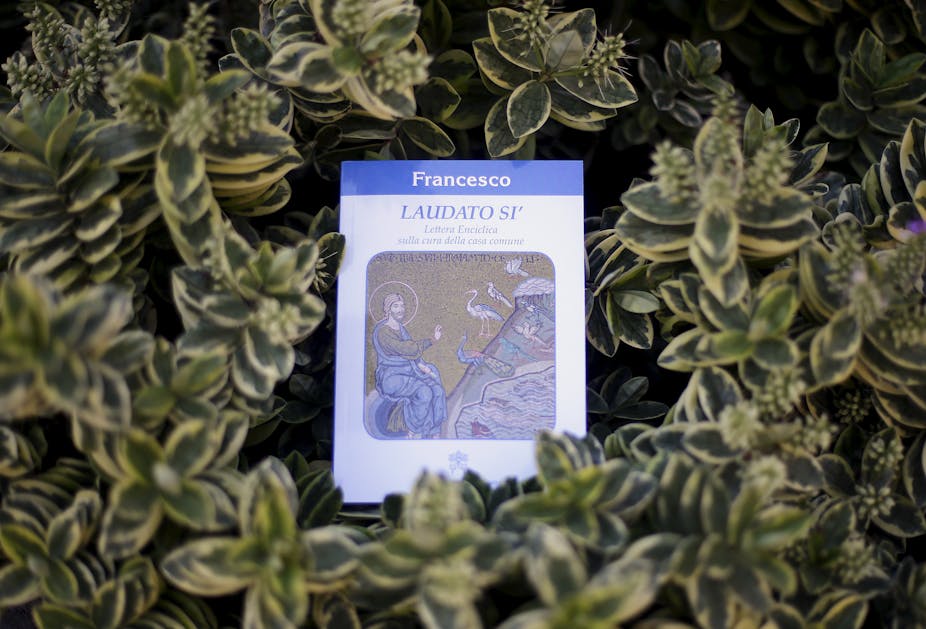

One of the problems in communicating about climate change is that it has been ghettoized as a strictly environmental message promoted by liberal messengers. This makes it easy for some to dismiss it. But the pope’s encyclical letter “Laudato Si’,” or “Praise Be To You,” kinks the arc of this conversation in some important and long-needed ways.

Whether it causes the profound changes that are necessary to fully address the “unprecedented destruction of ecosystems, with serious consequence for all of us” that he calls out is now up to us. Our challenge is nothing short of changing our values and beliefs.

In 1949, conservationist Aldo Leopold wrote that no important change in our ethical appreciation of nature could ever be accomplished “without an internal change in our intellectual emphasis, loyalties, affections and convictions. The proof that conservation has not yet touched these foundations of conduct lies in the fact that philosophy and religion have not yet heard of it.”

Today in 2015, the pope is taking concern for the environment and climate change to the level of our relationship with our God, our neighbor and our environment of which we are a part. If this truly takes hold, it will make the issue personally salient in ways that go far deeper than other attempts to stir attention and action. If people hear the message to address climate change and protect the environment from the church, mosque, synagogue or temple, it will have far more power to motivate action than a regulatory or economic message ever will.

Efforts to connect climate change to concerns for national security, economic competitiveness or human health are critically important, yet none can carry the weight and influence that the world’s religions can in motivating attention and action. These other messages can convince people to protect nature through self-interest, financial incentives and pragmatic reasons. Religious beliefs will compel us to act for reasons that go far beyond our narrow personal interests and evoke words like sacred, divine, reverence and love.

Root causes

And that seems to be a core element of the pope’s message. We protect and devote ourselves to what we love. In fact, I might add that if we don’t do this, we are doomed, both as individuals and as a species. The pope is calling that out, reminding us of the gravity of the situation and the deep connections between religious morality, social equity and environmental care.

This is about putting nature in its proper place within our deepest statements of faith and reexamining those statements that may have led us astray. This has been a much-debated and contested issue, one that exploded in 1967 when Lynn White wrote that our ecological problems derive from “Christian attitudes towards man’s relation to nature,” which lead us to think of ourselves as “superior to nature, contemptuous of it, willing to use it for our slightest whim.” He doubted that changes in those attitudes could occur unless, first, “orthodox Christian arrogance towards nature” were somehow dispelled and, secondly, we move beyond that idea that science and technology alone can solve our “ecological crisis.”

Pope Francis is calling us to dispel that arrogance. And where Lynn White’s essay caused an uproar of resistance, resentment and controversy, the pope’s message must, by definition, do the same. No “internal change in our intellectual emphasis, loyalties, affections and convictions” can occur without some discomfort and pain.

Indeed, if it did not, it would not be addressing the root causes of the issues to their fullest extent. Here Francis blames rampant consumerism, unrestrained faith in technology, blind pursuit of profits, political shortsightedness and the economic inequalities that force the world’s poor to bear the brunt of an imbalanced system.

This last point is at the center of his message. We live in a world where the richest 20% of the world’s population (namely us) consume 86% of all goods and services, while the poorest 20% consume just 1.3%. Even more startling is the fact that the three richest people in the world have assets that exceed the combined gross domestic product of the 48 least developed countries.

At the same time, it is these poor people that will bear the brunt of the environmental impacts of climate change. It is not a giant leap to connect these injustices with a call to act on climate change to fulfill and enact our religious beliefs.

Man’s domination of nature

Pope Francis calls for a reexamination of the meaning of “stewardship” within the book of Genesis and what it means to have dominion over nature. In the letter, he writes that our interpretation of dominion “is not a correct interpretation of the Bible as understood by the Church.”

Instead, he writes that the Bible teaches human beings to “till and keep” the garden of the world, where “‘tilling’ refers to cultivating, plowing or working, while ‘keeping’ means caring, protecting, overseeing and preserving.” This is a profound and unsettling challenge, one that will not go down easily. The fact that an encyclical letter could actually be leaked to the media and cause a media sensation speaks to the importance of its challenging message.

But in many ways, Pope Francis’ message may be the right message at the right time, though not necessarily a new one, even for a pope. In 1991, Pope John Paul II offered a similarly provocative counterpoint to the too widely accepted view of man’s domination of nature in his encyclical letter “Centesimus Annus” or “Hundredth Year”:

Man thinks he can make arbitrary use of the earth, subjecting it without restraint to his will, as though it did not have its own requisites and a prior God-given purpose, which man can indeed develop but must not betray.

But unlike his predecessor, Pope Francis has elevated concern for the environment in an encyclical letter all its own. This is unprecedented and reflects the unprecedented challenge before us. Aldo Leopold would be pleased.

Francis challenges us to turn our minds, hearts and actions toward nature and respect the value God created in it. Given our relatively newfound ability to alter the environment in globally catastrophic ways through climate change, we must protect nature for a reason greater and higher than our own personal self-interest – namely, that God wants and expects us to do so. That has the power to motivate a transformation of our world in ways that are urgently needed.

Adding a bright conclusion to this dark realization, Pope Francis writes that “Human beings, while capable of the worst, are also capable of rising above themselves, choosing again what is good, and making a new start.” Let’s hope, for all our sake, that he is right.