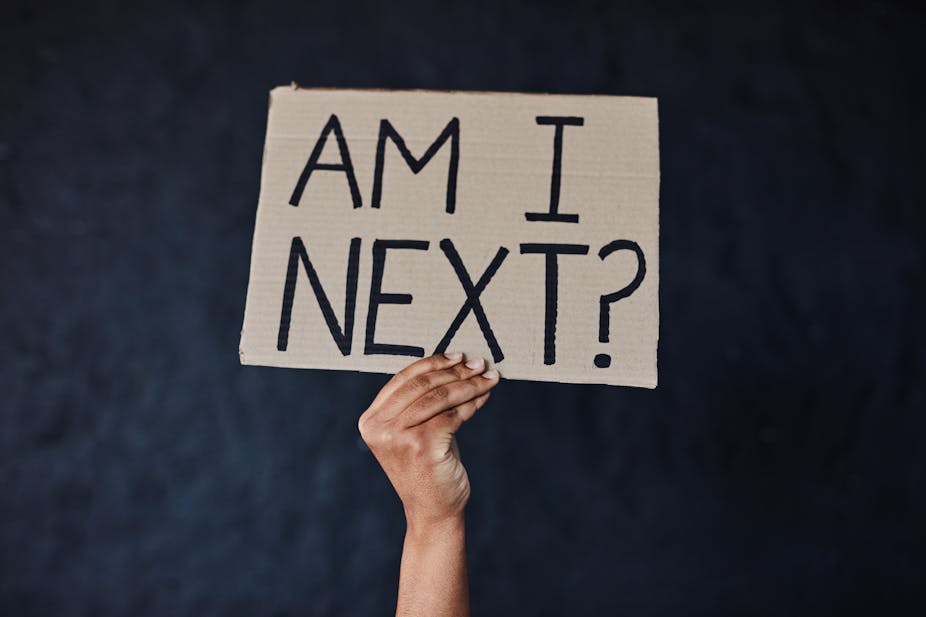

Rape in South Africa is systemic and endemic. The country’s annual police crime statistics confirm this. There were 42,289 rapes reported in 2019/2020, as well as 7,749 sexual assaults. This translates into about 115 rapes a day.

South Africa has one of the highest rape statistics in the world, even higher than some countries at war.

The picture has been more or less the same every year since the early 2000s, with the numbers going slightly up or down.

But policies to deal with the urgency of these very high levels of sexual violence tend to individualise rape in a way that creates the impression that only some men rape. And that they are the “rotten apples” or the “monsters”.

The response from the police – as well as the governing African National Congress (ANC) – underscores the failure to appreciate the systemic nature of the problem.

This was evident again recently at an ANC policy conference where it was clear that ministers and the ANC Women’s League continue to individualise rape. The conference agreed to a draft policy calling for chemical castration for rapists.

Read more: Gender-based violence in South Africa: what's missing and how to fix it

In my view, this is misplaced and shows a lack of understanding of rape as a social problem. Firstly, chemical castration does not work. Research has shown that chemical castration does not really contribute to reducing levels of rape. The reason for this is that chemical castration does not change attitudes – or the underlying violent behaviour of rapists. It merely acts as a punishment.

Secondly, the fact that the idea has been backed by the ANC shows that it continues to miss the point as to why men rape women.

Extensive research has been done on the motives of rape. The overwhelming conclusion is that rape is not about sexual desire. It is about power and an entitlement to women’s bodies.

This was horrifically illustrated in South Africa at the end of June when eight young women were brutally gang raped in West Village outside Krugersdorp, west of Johannesburg, while filming a music video on a mine dump. The crew was also robbed.

The perpetrators were brazen and felt entitled to inflict this brutal violation on young bodies. What happened in Krugersdorp clearly displays this type of entitlement by violating women’s bodies at gunpoint.

Missing the point

The state’s response to the attack was to round up 80 illegal miners, called Zama Zamas. Police statements suggested that they were foreigners who lived near the crime scene.

Very quickly the focus shifted from the brutal rapes and eight seriously violated women to illegal mining. The women became a footnote.

It is the same display of hasty work by the police to show that they are doing something. This has happened before such as in the case of the rape and killing of Uyinene Mrwetyana, a University of Cape Town student in August 2019. She was brutally raped and killed in a post-office when she went to collect a parcel. Action after the outcry from citizens about her senseless killing and protests quickly died down.

The latest attack also exposes police incompetence to deal with illegal mine workers who have been terrorising West Village for years. Illegal miners allegedly regularly rape women from West Village, and despite women reporting the rapes, the police were reluctant to investigate.

Read more: Artisanal gold mining in South Africa is out of control. Mistakes that got it here

But the “foreigners are responsible for rape” narrative is the same as men being singled out as “bad apples”. It ignores the systemic nature of rape in South Africa. And it creates the impression that South African men do not rape. The high statistics, however, show that many South African men rape.

Understanding rape

Intimacy and injury, a recent book on #MeToo and how it was experienced in the Global South, makes it clear in the introduction that women in post-colonial societies bear the brunt of government intransigence to deal with violence. They write:

newly independent nation states and local elites failed to take account of this {sexual violence}, in spite of elaborate rhetorical commitments, leaving feminists to push for state and law to redress long histories of sexual violence. Political leaders and state functionaries – the police and the army – participated in an overall culture of normalising sexual violence and promoting a high tolerance for such violence over other crimes. Sexual violence has been at the heart of feminist concerns in India and South Africa … (p5-6).

What this suggests is that when rape is normalised, dealing with rape after it has occurred is too late. Preventative measures need to be put in place, such as addressing high levels of crime, including rape with impunity.

And the attitudes of men about women’s bodies and toxic masculinity need to be addressed through state level interventions, especially in schools to change the socialisation of boys.

The state should also prioritise the upgrading and resourcing of laboratories where forensic DNA evidence is analysed. The huge backlog in South Africa means that victims wait for justice for years, and may never get it.

In 2017 the government was forced to take decisive action on gender based violence following a series of marches and protests by activists who mobilised under the banner #TotalShutDown. They demanded action against gender-based violence. In the wake of this activism a National Strategic Plan on Gender Based Violence and Femicide was developed, and is now being rolled out.

This plan rests on six pillars:

accountability and leadership;

prevention and rebuilding social cohesion,

justice, safety and protection;

care, support and healing;

economic empowerment; and

research and information management.

The plan speaks to the systemic nature of gender based violence. But it also clearly shows that it will need long term efforts, with success only being determined over time.

Read more: Change what South African men think of women to combat their violent behaviour

The truth is that there are no easy and quick fixes, such as the ANC’s recent castration idea which falls short on a range of scores. Firstly, because rape is about power. This is evident from the fact that many rapes are committed with objects such as sticks, brooms and glass bottles. So, those who are chemically impotent will find other ways to violate women.

Secondly, such a policy would violate the human rights of perpetrators, such as bodily integrity. Rapists still have human rights even when convicted of rape. Such a law would therefore, also be unconstitutional.

What rape does

University of Stellenbosch philosopher Louise du Toit, in her book The Philosophical Investigation of Rape, clearly explains the damage of rape – as an injury of the spirit. It destroys the victim’s sense of self, her trust in others and her trust in the world.

These are things that cannot be regained. As she states on p85

The horizon of this new, shrunken world is the victim’s physical pain, fear of death and actual reduction to the less-than-human… {she} is reduced to her body, lived as a thing, object, inanimate, finite, mortal…

This is the trauma, which the eight women raped in Krugersdorp, now have to live with. As well as the tens of thousands of South Africa’s other rape victims.