Public anxiety over immigration was a key factor in the Brexit referendum result. The government’s recent proposals for a new post-Brexit immigration system, which will put an end to the free movement of people from the EU, are intended to ease this same anxiety.

Yet, the emphasis of the new proposals is on meeting the future skills requirements of the domestic labour market. Commentators quickly pointed out that concerns over immigration are not always strictly economic in nature, and perceived threats to British culture and identity may be equally important.

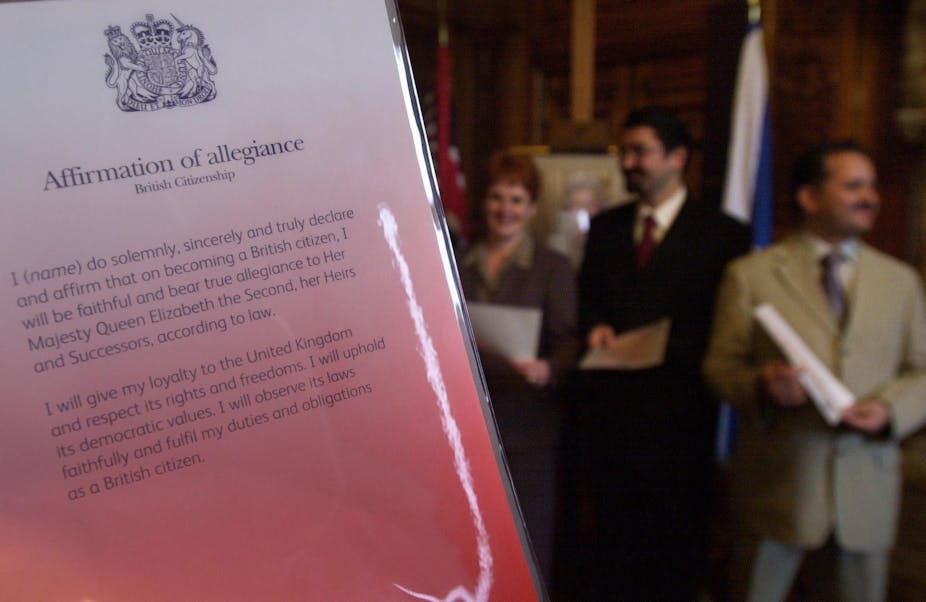

The perception that people in some minority groups lack a sense of belonging in the UK has led successive governments to introduce policies explicitly promoting British values. Unease around these issues has arguably also increased opposition to the admission of refugees and family migrants, who tend to arrive from countries that are culturally quite distinct from the UK.

Official nervousness around refugee arrivals was apparent during the refugee crisis in the summer of 2015, and again in recent weeks, as the government declared a “major incident” over the small number of people trying to reach the UK in boats across the English Channel.

Feelings of Britishness

My recent research suggests that people who came to the UK as refugees or family migrants are much more likely than economic migrants to feel that they have a British national identity. A family migrant is anyone who said they originally migrated to accompany other family members, or to join family members who are already here. My analysis was based on data from the UK Labour Force Survey, which contained interviews with more than 76,000 migrants between 2010 and 2017. While 25% of economic migrants reported feeling British, this rose to 53% for refugees and 62% for family migrants.

Even when comparing only migrants who came to the UK from the same countries of origin, and accounting for differences in their age at arrival, time since migration, ethnicity, and educational background, refugees and family migrants still stood out as the most likely to say they felt British.

This type of descriptive research only attempts to analyse patterns of British national identity over the relevant time period. It cannot be used to establish definitive explanations for these patterns, or to make predictions about what would happen in different future immigration scenarios.

Yet, the most simple and general explanation for my finding is that refugees and family migrants are more likely than economic migrants to plan to stay in the UK long term. The defining characteristic of an economic migrant is their pursuit of employment, which may or may not be viewed as a long-term arrangement. In contrast, a family migrant is defined by their attachment to family members in the country, and a refugee is defined by their having arrived in the country after fleeing war or persecution. In both these cases, a migrant’s anticipated length of stay in the UK is likely to be longer term.

It’s possible to more or less eliminate some other possible explanations for this finding. For example, I show in additional analysis that the result is not driven purely by a higher uptake of legal citizenship among refugees and family migrants, or by a higher proportion of family migrants arriving from countries in the British Commonwealth. Although citizenship and Commonwealth origins do seem to matter for identity, among people who are not British citizens, refugees and family migrants are still more likely to report a British identity. The same is true among migrants who come from countries outside the Commonwealth.

Longer stays

A large body of previous research suggests that other important aspects of migrant life – such as language learning or completing new qualifications – are shaped by how long a person intends to stay in their new country. This makes sense: learning the language to an advanced level or completing a qualification that is only recognised in the new county may simply not be worthwhile if one intends to leave before long.

The same logic could apply in the case of adopting a new national identity: for many who intend to stay for the foreseeable future, it is natural to develop a sense of feeling “British”, while for others it isn’t. A change in national identity may be more difficult than physically crossing an international border.

There’s no need for the UK to wish all migrants to feel British. All sorts of people migrate to the UK for different reasons, hopefully improving their own lives in the process, as well as contributing to the domestic economy and culture in different ways. It would be strange to suggest that a short-term migrant should or could adopt a British national identity, though it would perhaps be a sign of a healthy, inclusive national culture if a proportion of longer-term migrants did so. These matters of culture and identity are worth considering alongside strictly economic criteria in response to public anxiety over immigration.