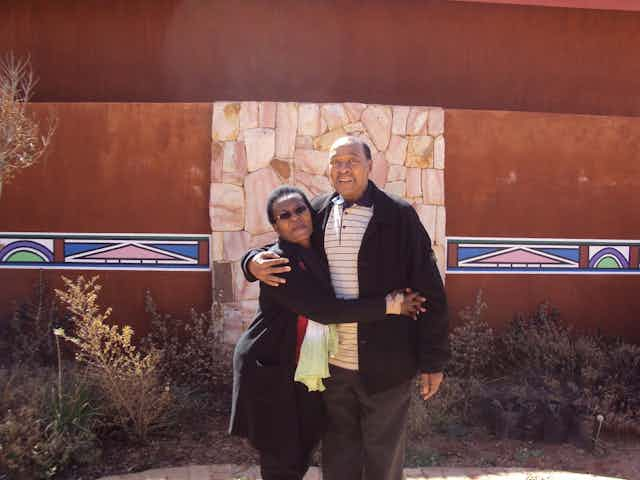

The pioneering South African artist Louis Khehla Maqhubela passed away on 6 November 2021 at St Thomas’ hospital in London, UK, a few days before his wife Tana Maqhubela also passed. He leaves behind an important and iconic legacy.

He created a bridge for South Africa’s urban, black ‘township artists’ of the 1950s, 60s and 70s. The move that he offered away from prescriptive expressionism and into internationalist styles and concerns can hardly be overestimated.

Early years

Maqhubela was born in Durban, South Africa, in 1939. His parents moved to Johannesburg in 1949, while he and his sisters were sent to live with their aunt in the rural town of Matatiele in the country’s Eastern Cape province, until they joined their parents three years later.

Maqhubela was a member of artist and teacher Durant Sihlali’s weekend artists group from 1955 to 1957. From 1957 to 1959, while still at school in Soweto, he studied under the direction of Cecil Skotnes – known for his painted and incised wooden panels, woodblock prints, tapestries and sculpture – and sculptor Sydney Kumalo at the Polly Street Art Centre. The centre was housed in a hall in Johannesburg and focused on black art students. It exhibited artists of all races, defying the racial segregation of the white minority government’s apartheid policy that saw black citizens moved into townships outside of cities.

Maqhubela started work as a commercial artist but from 1960 he was commissioned to create paintings and mosaics in hospitals, schools, halls and bar lounges in and around Soweto township. Skotnes facilitated a commission to create four large-scale oil paintings for public buildings. The only extant one is Township Scene (1961).

It demonstrates a vitality, rigorous draughtsmanship and the use of strong non-descriptive colour and expressionistic paint application that distinguishes it from the more stereotyped impressions of black, township life popular at the time.

Despite working in a hostile apartheid environment, Maqhubela excelled and had success early in his career.

A transformative trip

He won first prize at the Adler Fielding Gallery’s annual ‘Artists of Fame and Promise’ exhibition in 1966 with a monumental conté drawing called Peter’s Denial. Namibian-born artist Stanley Pinker was the runner-up and Maqhubela became the first to cross the divide between black and white South African artists. His work was much in demand.

Maqhubela’s prize included a return air ticket to Europe; he was already well informed and read, but the three months spent abroad transformed his life and work.

In the great museums and galleries, he encountered the masters of Modernism and abstraction. A major exhibition of Swiss-German artist Paul Klee’s work in Paris had a profound impact on him.

Passing over a chance to meet the famous painter Francis Bacon, Maqhubela went to St Ives in Cornwall to see South African-born artist Douglas Portway. In Portway he found not only a mature and exceptional painter, but also a kindred spirit, someone in search of creativity and expression beyond observed reality, someone who explored the spiritual and metaphysical realms of making art. In an interview appearing in The Star newspaper in 1968, shortly after his return, Maqhubela said: “I learned a lot from him. We spent many hours discussing art and techniques.” His own path to a divine source was as a student of the Rosicrucian Order.

Maqhubela’s break with the past and his new direction meant the end of figurative expressionism, with its emphasis on the human figure, and the beginning of a personal engagement with modernist abstraction, referencing forms and shapes. This was accompanied by the development of an artistic language and iconography inspired by his quest for spiritual growth. His paintings in oil on canvas or paper of the 1970s are characterised by thinly applied layers of paint articulated by means of scraffito, sometimes completely abstract, at other times with figures, birds and animals emerging from the wiry lines, colour and floating shapes.

An abstract artist emerges

Maqhubela was successful, but the obstacles he and his family faced in apartheid South Africa proved too great for them. They moved to the Spanish island of Ibiza in 1973 and settled in London in 1978.

He studied at Goldsmiths College (1984-85) and the Slade School of Art (1985-88). At the Slade, Maqhubela was exposed to printmaking and in 1986 he produced a series of etchings that count among the most significant in his oeuvre. He continued to exhibit extensively in South Africa, in group as well as solo shows and featured prominently in Esmé Berman’s book, The Story of South African Painting (1975).

Stimulated by his new environment, and artists such as Wilhelmina Barns-Graham and John McLean, Maqhubela’s work became increasingly abstract.

A trip to South Africa in 1994 to experience first hand the euphoria of freedom that followed the country’s first democratic elections, and again in 2001 to receive medical treatment, had a powerful impact on Maqhubela. This gave renewed impetus to his work, bringing thematic and technical changes.

Major collections

In 1998, Maqhubela’s gouache on paper, Tyilo-Tyilo (1997), was purchased by the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, in the USA. The painting celebrates the music of the 1960s from the South African townships. The year before, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, UK, acquired an untitled Maqhubela oil painting with etching on paper. It depicts etched figures, lines and shapes with a dreamy, child-like quality, yet the careful composition reveals the hand of a master draughtsman.

The artist is represented in all the major public collections in South Africa. The exhibition A Vigil of Departure – Louis Khehla Maqhubela, a retrospective 1960-2010 first opened at the Standard Bank Gallery, Johannesburg in 2010 and travelled to the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town and the Durban Art Gallery.

The exhibition, together with the extensive catalogue, offered South Africans the opportunity to welcome and embrace a significant artist who, for too long, had been absent from the national consciousness and art history books.

Maqhubela had no immediate successors in the stylistic sense: his art was perhaps too personal and private, too enigmatic to emulate, but – understanding that there was a world beyond the immediate and visible and that it could be revealed through art – he served as a source of inspiration for his compatriots and artists everywhere.