A new monument of political activist and leader of the Indian independence movement Mahatma Gandhi has been unveiled in London’s Parliament Square. Gandhi’s statue will join that of his famous adversary in the independence campaign, Winston Churchill, as well as others, among them Nelson Mandela and Abraham Lincoln. He is the only person never to have been in public office to be honoured with a statue in the square, and the first Indian.

The memorial’s inauguration coincides with a season of commemorations that mark the 100th anniversary of Gandhi’s return to India from South Africa to begin the struggle for self-rule. Yet the statue in London is also testament to Gandhi’s profound relationship with Britain: of both the considerable influence and impact Gandhi had in Britain itself, but also the influence Britain had on Gandhi.

Shaping Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi first arrived in Britain at the age of 19 on September 29 1888 to study law. He initially found lodgings in West Kensington. His ambition then was to transform himself into an English gentleman – and pictures from the time show him in contemporary Victorian court dress.

He trained as a lawyer at London’s Inner Temple. While in London, Gandhi discovered the Vegetarian Society, a lively London-based reformist movement that originated in the late 19th century. This shaped his own views on vegetarianism and formed part of his political awakening. Non-violence and vegetarianism soon became aligned in Gandhi’s thinking on politics and ethics.

His involvement in the society provided Gandhi with access to some of the notable thinkers of the time. While in London, Gandhi attended meetings of the London Indian Society as well as other organisations that campaigned for greater self-rule. He also got involved with the Theosophical Society.

Gandhi’s three years in London profoundly shaped him and his thinking. After he was called to the Bar in 1891, he returned to India, before moving to South Africa.

The home front

In 1906 Gandhi returned to the UK, travelling to London to campaign for the rights of the Indian community in South Africa as the spokesman for Natal and Transvaal. He again represented the cause in London in 1909.

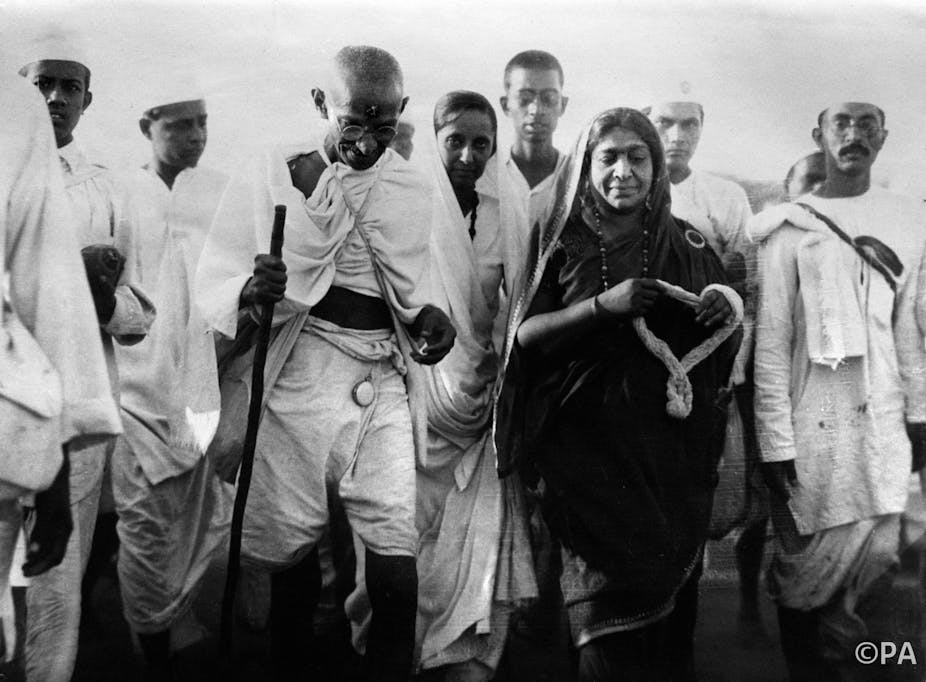

In August 1914, a longer four-month stay coincided with the outbreak of World War I. While in the city he reconnected with many activists for Indian self-government, including the poet Sarojini Naidu. Gandhi galvanised the local Indian community to support Britain’s war effort. He was a driving force behind the creation of the Indian Ambulance Volunteer Corps and also contributed to the recruitment of Indian medical staff for the hospitals along Britain’s south coast. These hospitals were set up to care for Indian soldiers wounded on the Western Front.

The British working class

Gandhi visited Britain for the last time in September 1931 to attend the Second Round Table Conference on the future of India. By this point, his reputation as a campaigner had grown exponentially and so his visit elicited much interest in the press.

However, his activism and humility also connected him to the British working classes, as archival footage reveals. Rather than staying with other delegates in central London hotels, Gandhi instead resided in lodgings in the humbler area of Poplar, East London.

During this visit the East End doctor Chuni Lal Katial, who acted as Gandhi’s chaperone, arranged for Gandhi to meet with Charlie Chaplin. Gandhi also visited mill workers in Darwen, Lancashire at the invitation of the mill-owning Davies family.

The intention was to alert Gandhi to the impact the Indian boycott of British goods had in north-west England, and in particular the hardship being suffered by the local textile industry and its workers. Though the circumstances of his visit were potentially contentious, he was accorded a warm reception. Gandhi expressed his sympathies with the workers’ plight, though not necessarily the mill owners’. His prominent visit helped to explain the issues of poverty and oppression India and her people faced. It became clear that unless an agreement for Indian self-government could be reached the campaign for independence would continue.

Gandhi’s influence has left a lasting legacy on non-violent resistance struggles across the world. The new London statue is testament to his work, and the ongoing, manifold connections between India and Britain. More than this though, the unveiling of the first statue of an Indian in Parliament Square is a tribute to the broader and complex underrepresented contributions South Asians have made to Britain across the decades.