In the Edinburgh World Heritage website’s story about Scotland’s bard, it notes that when Robert Burns “the ploughman poet” came to the city in 1787, he was “a new boy in town and a great looking heart throb”. It’s a familiar description, dating back to the writer Henry Mackenzie’s review of the iconic Kilmarnock edition of Burns’ poetry in The Lounger for December 1786, describing him as “the heaven-taught ploughman”.

The comparison Mackenzie intends is one with Shakespeare as portrayed by Milton in L’Allegro, whose “wood-notes wild” derive not from education but from inspiration: Burns is to be for Scotland what Shakespeare was for England.

But it was the ploughman label that stuck. Burns is often seen as a “peasant poet”, aligned with the likes of English writer John Clare – and he probably wouldn’t have had it any other way.

Farmer glories

During his lifetime, Burns presented himself as “nature’s bard”, ignorant and free of the “rules of Art”. He walked round Edinburgh in farmer’s boots, portraying a deliberately rustic air.

Yet Burns was well read and reasonably educated: he knew the work of Dryden, Fielding, Goldsmith, Milton, Pope, Sterne and many others. He appears to have been influenced both by French bawdy poetry and the troubadour tradition of Provence. In the preface to his Poems (1786), Burns identifies himself as “obscure” and “nameless”, yet cites Virgil and Theocritus.

And Burns certainly wasn’t living in deprivation. He earned much the same from his Edinburgh edition of Poems in 1787 as Adam Smith did from The Wealth of Nations, and in the 1790s his income was as high or higher than Jane Austen’s. It was similar, in fact, to those ministers of the Kirk he liked to bait so much.

He was supported by many wealthy Freemasons. He was the regular correspondent of gentlemen in a strongly class-segregated era, and dined with them. Yet Burns is still often remembered as if he was living on the margins.

This image absolutely suited him: his greatness appeared to be a mystery – and mystery is a lasting source of power. He seemed to have sprung from the soil with no visible means of support. A “celebrity” in the modern sense of a famous person is a 19th-century word: Burns was arguably the first poet to think of himself as a brand.

Brand Burns

This self-creation helped to bring him both national and international recognition. In Germany, he came to be seen as both representing the progressive universalism of the radical Enlightenment and a one-stop shop for the folk tradition.

In America he was perceived as the good European, the man of “independent mind” who was a foe to tyrants and an adoptive son of the United States. In the British Empire, he represented the sentiment, communitarianism, egalitarianism and humanitarianism on which many Scots liked to congratulate themselves.

In the USSR, he came to be the “good kulak” (peasant) who would have understood the benefits of collective farming, and the Soviets became the first to issue a commemorative stamp for the poet in 1956.

In China during the Cultural Revolution, he represented the lack of contradiction between the agricultural and intellectual; for Kofi Annan in an United Nations address in 2004, he was the supreme internationalist, the advocate of harmonious neighbourliness worldwide.

Much of this affection stems from the fact that Burns is in many respects the supreme poet of sentiment, certainly in the Anglophone world. We overlook that his paeans to the routine life of rural poverty are distanced by education: in The Cottar’s Saturday Night, he quotes Alexander Pope’s Windsor Forest; in Tam o’ Shanter, he knowingly celebrates sex, drink and dancing in the narrative voice of the Romantic collector of tradition, in a story he invents and sends to such a Romantic collector.

When Burns is knowingly sophisticated, he sometimes appears transparently simple: in Auld Lang Syne the praise of a vanished past, the persisting nature of relationships despite the transience of life, the sugaring of nostalgia, all deflect us from the lack of any promised future. Again we see what we want to see: from It’s A Wonderful Life to When Harry Met Sally and beyond, Hollywood has recognised the song’s extraordinary evocation of sentimental intensity.

Similarly, people often project a political agenda onto Burns that is hard to justify. In To a Mouse, for example, the ploughman does nothing to help the mouse.

Nor is the nature of “Man’s dominion” changed really, despite the ploughman being “sorry” for it. Sorry doesn’t cut the mustard, but the sentiment buttered Burns’s bread and still does worldwide. Most of his supposed politics turns out to be more feeling.

Supper man

The other element that has done much for the poet’s reputation is the Burns Supper. The first was in Alloway in Ayrshire on July 21, 1801 – celebrations switched from his date of death to his birth later, possibly influenced by the adjacent date of dinners on January 24 for the great British Whig Charles James Fox.

The custom of the Burns dinner or supper spread rapidly. We see it in London in 1804, India in 1812, New York in 1836, and Copenhagen, Paris and Madrid by 1859.

Today, some nine million people attend official Burns Suppers each year alone, and 100,000 Immortal Memories are given. Scotland’s Year of Homecoming was built around Burns in 2009, and in 2018, Scottish Nationalist MSP Joan McAlpine’s parliamentary motion on Burns’ importance to the Scottish economy gained cross-party support.

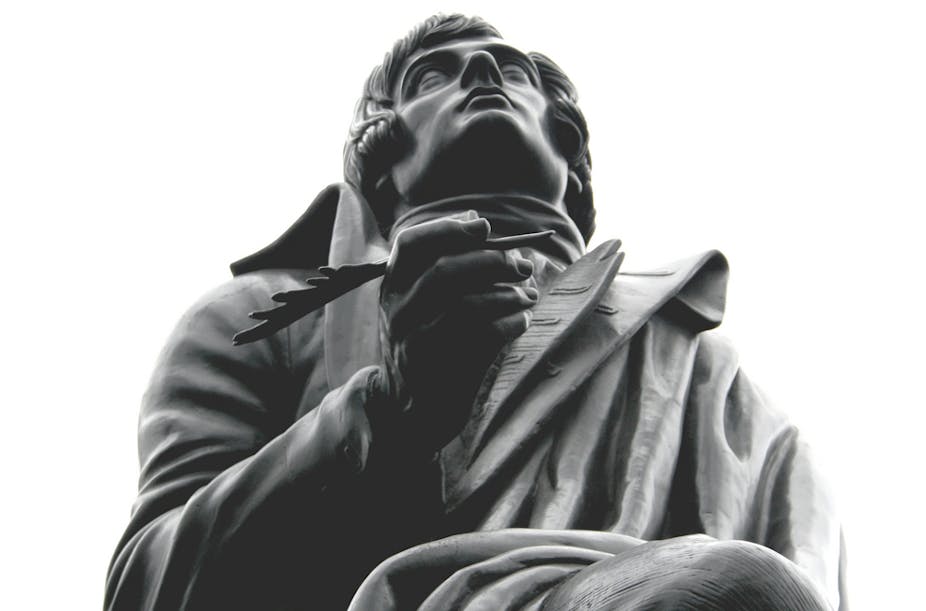

Burns has been translated several times as often as Byron; he has more statues than any secular figure except Queen Victoria and Christopher Columbus; and is the only person to have appeared on a Coca Cola bottle. He’s a synecdoche of the way Scotland wants to be perceived: humane, egalitarian, caring, international.

“O wad some Pow'r the giftie gie us/ To see oursels as ithers see us!” The memory of Robert Burns is indeed immortal. And he knew what he was doing all along.