The mortal fight against apartheid is usually cast in terms of good versus evil, a simple schism in which there are heroes and villains, or racially, in a white against black equation that blots out pretty much all else in between. But of course, this is hardly ever the case.

Apartheid – and the racial segregation it was based on – thoroughly tested ethical principles and stances, made unlikely heroes of some and improbable scoundrels of others. It besmirched moral lenses more often than not. And because the sight it proffered isn’t usually pretty – and to protect the collective sanity of South Africans – there had to be neat ethical resolutions for untidy political and moral dilemmas.

The result was that many individuals fell through the cracks in the unfolding story of apartheid’s collateral damage.

One such figure is Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, the formidable founder of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC). He is the subject of a May 2022 Robben Island Museum hosted exhibition titled, “Remember Africa, Remember Sobukwe”

Sobukwe, in very trying times, remains an unsung hero in the epic moral fight against the evil that was apartheid. He was a political leader, a social activist and genuine humanist who stood undaunted and undefeated by the deadly curveballs apartheid threw at him.

History written by the victors

Sobukwe casually subverts apartheid’s assumed ethical linearity by adding what is now unjustly viewed as a minority voice. Dubbed “Biko before Biko”, he was once perceived to possess more revolutionary potential than Nelson Mandela. Steve Biko was the charismatic leader of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) during apartheid. He rallied South African youth in collective rebellion while at the time lavishing them with much-needed hope.

In attempting to dismantle apartheid’s vice-grip, Sobukwe discountenanced suggestions and methods of integrationism, a stance that saw him part ways with the African National Congress (ANC). This led to the formation of his own still surviving movement, the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania in 1959.

There’s an African proverb that speaks directly to what many perceive to be Sobukwe’s undervalued status in South African political history. The proverb, popularised by author and poet Chinua Achebe, goes like this: that lions need to become historians in order to truthfully narrate their own history otherwise the tale of the hunt would always end up glorifying the hunter.

The ANC – and not the PAC – emerged victorious at a winner-takes-all contest that marked the end of apartheid. Due to this outcome, Sobukwe’s historical significance naturally receded.

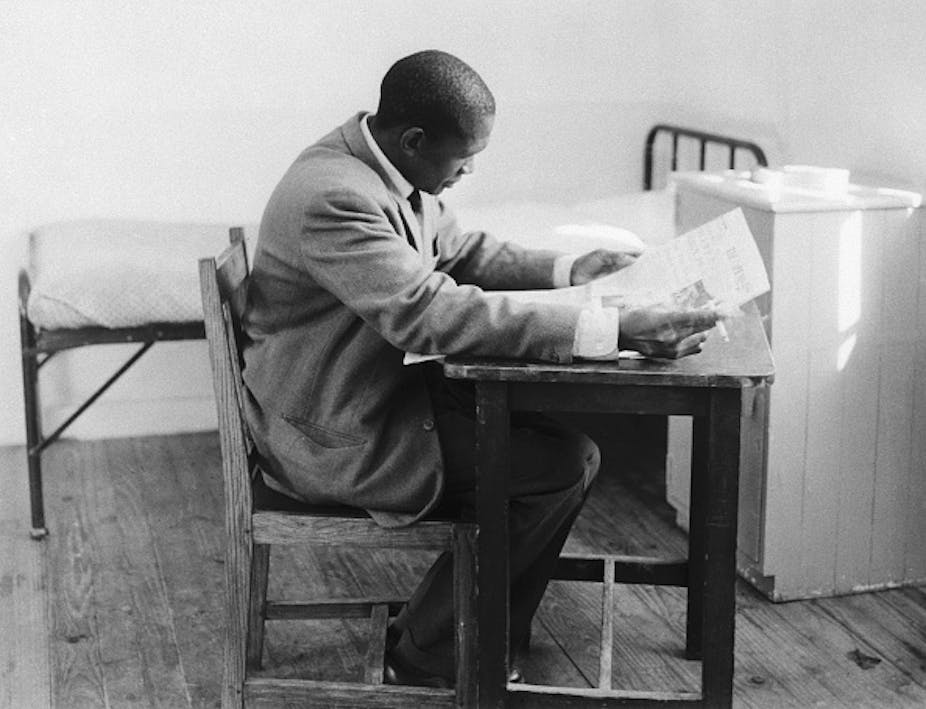

Even under apartheid, Sobukwe could have had a much easier life if he chose. In 1954, he was appointed as a lecturer in the Department of Bantu Languages at the historically white University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. The importance of education was instilled in him as a boy together with his siblings by his struggling parents. Even in imprisonment, Sobukwe would acquire a degree in economics and another in law after he was released. Understandably, he was called “Prof.” by his associates and well-wishers.

However, Sobukwe was not content to live within the comforts provided by academia. He had joined the radical wing of the Youth League of the African National Congress. He subsequently became the editor of the uncompromising periodical, The Africanist.

Within the ANC, an ideological crisis occurred between those who were deemed moderates and the radicals. The moderates favoured an integrationist and gradualist approach to the sociopolitical impasse created by apartheid. Radicals such as Sobukwe supported an African revolution driven by Africans and for Africans without any accommodationist overtones.

The unresolved crisis meant he had to abandon the ANC and form the PAC instead.

Incarceration and banishment

In 1960, Sobukwe launched the Positive Decisive Campaign to peacefully protest the apartheid pass laws. He had informed the apartheid authorities of his non-violent protest. Nonetheless, the authorities responded by massacring 69 individuals at Sharpville. Applying the Criminal Law Amendment Act with criminal intent, Sobukwe was sentenced to three years of incarceration with hard labour served at Pretoria Central and Witbank Prisons.

When the time for his release came, parliament promulgated the Sobukwe Clause which saw him serve another six years at the notorious Robben Island. But he refused to be broken. He studied, taught, exercised and kept up steady correspondence with family and friends.

After he was eventually released, he was banished to Kimberley where he had no family and friends which must have felt like another spell of solitary confinement. Indeed his life was never the same after his indictment and incarceration. From that time until his eventual death from lung cancer in 1978, he was severed from family, friends, medical care and economic opportunities.

The intention of the apartheid regime had been to annihilate him psychologically and physically. They humiliated and starved him and also denied him permission to take up opportunities offered to him in the US. Indeed the systematic torture and horror meted out to him by the apartheid authorities were simply mind-blowing. They created a concatenation of arid dungeons for which there was no escape specifically for him.

When he died, his burial was arranged by the Azanian People’s Organisation (Azapo) at Graaff-Reinet and was attended by 5,000 people. Evidently, Sobukwe, even under the most intolerable conditions, had been effective in inspiring an ever loyal corps of freedom fighters who continued his invaluable work.

Sobukwe was principled, uncompromising, dedicated and courageous. When hope faltered and died, he resurrected it, where the enervated cried out for help and succour, he provided them. And as many of his faithful followers at the Robben Island Museum exhibition testified, he was undoubtedly a man for all seasons.