Darwin’s theory of evolution is a simple but powerful framework that explains how complexity can come from simplicity: how everything biological around us – from the microbial biofilms on your teeth to the majestic redwood trees – emerged from the very simplest of beginnings.

How exactly this happened is, of course, a matter of intense research. Each species is finely adapted to thrive in its environment, which in turn has shaped that species’ evolutionary history. But those environmental forces exerted on a species occurred over a very long period of time, in the often very distant past. How can we understand which environmental features were responsible for which adaptations we see today?

As an example, my research group recently got interested in what makes people dislike taking risks. Of course we can’t travel through time to go back and run a controlled experiment on our early human ancestors to see how that tendency might have evolved. But as scientists, we want to do more than just come up with an untestable hypothesis.

So we turned to computers to simulate the dynamics of ancient people for thousands of generations. By carefully choosing the starting parameters for our computer simulation, we were able to see how in small groups of about 150 people – the size common during the Stone Age – gambles that pay off big time (but only rarely) end up being genetically costly. We also found that risky behavior had no consequences as long as populations were large. I can’t think of another way an evolutionary study like this could have been carried out. Here’s why we can believe what these kinds of computer simulations tell us.

Passing on a constant flux of traits

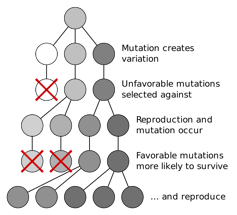

Darwin’s theory of evolution is simple in the sense that it requires only three necessary (and sufficient) components for the process to work: inheritance, variations and differential survival (sometimes called “selection”).

Inheritance guarantees that anything new discovered by the process is not lost. Variation ensures that new things are being tried out constantly. And differential survival implies that differences matter – variations that help rather than hurt have consequences for the descendants of the first individual that carried that beneficial change.

But even though these principles are straightforward, how they play out in a complex world is far from simple. We might be able to work out in our head how one beneficial change (say, a larger body size that allows an individual to withstand a predator’s assaults) can also have negative consequences (more time spent foraging to support the body weight exposes the individual to more predation). Such simple trade-offs can be captured by mathematical formulas, and their consequences can be worked out.

But in real biology, every single trait could conceivably affect every other. It’s not easy to work out the net benefit of a set of traits, either in your head or with mathematics. This is where computers come in.

Computers run through scenarios, fast

What computers really do within scientific research is often misrepresented or misunderstood. I frequently hear the phrase: “With a computer, you can get any result you want.” But this is not true. What a computer does is keep track of things for you.

To a large extent, this is what mathematics does too. I like to point out that mathematics is “the crutch of the feeble-minded”; it allows us to use symbols to embody complex relationships that we can then manipulate according to strict rules.

The computer is no different, except it allows us to keep track of vastly more variables, and to work out the consequences of the relationships over long periods of time. Since we set strict rules, of course, we can’t get “anything we want.” We get only what is allowed according to the rules.

But what are those rules?

In mathematics, you start with a set of assumptions, and you work out the consequences according to the rules of logic. This is still true inside a computer, but now we can also implement very specific rules – for example, the laws of chemistry, the effects of friction or the cost of finding a mate.

Researchers in a variety of fields turn to computer simulations to help them test ideas that they can’t investigate any other way. Astrophysicists use these kinds of models to simulate how stars form. Material scientists simulate the aging of nuclear weapons to predict if they will still work in the future.

In evolutionary biology, we might ask which factor shaped a particular trait or behavior. For instance, my colleague Kay Holekamp has been observing hyenas in Kenya for over 25 years, and she’s collected an enormous data set pertaining to the hunting habits (among other traits) of these animals. But even all those observations can’t tell us why she sees what she sees in the field. The reasons may lie in pressures that the population was under in the past, or maybe the pressures manifest themselves only over thousands of generations.

To answer questions such as “Why don’t the highest-ranking female hyenas participate in the hunt?,” we have to study the consequences of different assumptions on the long-term survival of the group.

Evolutionary theory says that only beneficial traits survive in the long run, but it can often be hard to understand how a certain trait might help. This is because of all those trade-offs I mentioned, and sometimes the benefit of a trait only becomes clear after a long time. After all, evolution has had millions of years of trials, failures and successes. Even 50 years of observation might not reveal to us the long-term consequences of a set of traits and how they interact and play out in a complex world.

But a computer might work this out in minutes, as a population of 1,000 gazelles and a group of, say, 150 hyenas can be followed over thousands of simulated generations.

Matching theory to observation

In evolutionary science, computers thus are prediction machines: they answer questions like “What would happen under these rules, given I started in this world with these starting conditions?”

In our study of the evolutionary origins of risk aversion, for example, we could ask what happens to risk aversion if the total population was large, but composed of small groups with migration between them. Running the scenario, we found that risk aversion still evolved unless the migration rate was exceedingly high.

Of course, if you start with the wrong rules, or inappropriate starting conditions, the results may not match what we observe in reality. But this is exactly what we require in the scientific process. If the predictions are wrong, then we must modify either the rules, or the initial conditions (or both).

Once we do obtain a match between the computer simulations and real-world observations, we can’t stop there and conclude we’ve discovered the rules that correctly reflect what is happening in nature. We must, instead, test whether these rules also predict other things that we didn’t set out to test in the first place. For example, do the same set of rules also explain the observation that the spoils of a kill are not distributed equally among the hyenas?

This kind of thinking is no different from the way theory and experiment have worked in unison to build the complex and powerful framework of theoretical physics. In that quest, theories were laid down, for the most part, mathematically. In evolutionary biology, though, this is usually not possible simply because biology is too complicated.

Evolutionary simulations allow us to test hypotheses, but they’re not asking or even answering questions. We ask “What if,” and the computer dutifully responds: “In this case, this is what you would get.” The computer helps us “think forward in time” with blazing speed, and in evolutionary science this is precisely what is required to generate understanding.