Soon after it became a British colony, New Zealand began shipping the worst of its offenders across the Tasman Sea. Between 1843 and 1853, an eclectic mix of more than 110 soldiers, sailors, Māori, civilians and convict absconders from the Australian penal colonies were transported from New Zealand to Van Diemen’s Land.

This little-known chapter of history happened for several reasons. The colonists wanted to cleanse their land of thieves, vagrants and murderers and deal with Māori opposition to colonisation. Transporting fighting men like Hōhepa Te Umuroa, Te Kūmete, Te Waretiti, Matiu Tikiahi and Te Rāhui for life to Van Diemen’s Land was meant to subdue Māori resistance.

Transportation was also used to punish redcoats (the British soldiers sent to guard the colony and fight opposing Māori), who deserted their regiments or otherwise misbehaved. Some soldiers were so terrified of Māori warriors that they took off when faced with the enemy.

Early colonial New Zealand had no room for reprobates. Idealised as a new sort of colony for gentlefolk and free labourers, New Zealanders aspired towards creating a utopia by brutally suppressing challenges to that dream. On 4 November 1841, the colony’s first governor, William Hobson, named Van Diemen’s Land as the site to which its prisoners would be sent. The first boatload arrived in Hobart in 1843 and included William Phelps Pickering, one of the few white-collar criminals transported across the Tasman. Pickering later lived as a gentleman after returning home.

In 1840s Van Diemen’s Land, convict labourers were sent to probation stations before being hired out. Many men transported from New Zealand were sent down the Tasman Peninsula, where labourers were needed at the time.

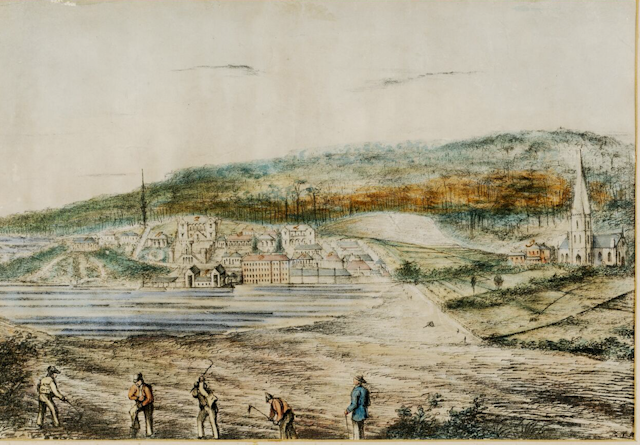

Ironically, those eventually allocated to masters or mistresses in larger centres like Hobart or Launceston would have enjoyed more developed living conditions than New Zealand’s fledgling townships. In those days, Auckland’s main street was rather muddy. Early colonial buildings were often constructed by Māori from local materials.

At least 51 redcoats were shipped to the penal island. Some committed crimes after being discharged from the military. But many faced charges related to desertion. Four of the six soldier convicts who arrived Van Diemen’s Land in June 1847 were court-martialled in Auckland the previous winter for “deserting in the vicinity of hostile natives”.

As Irish soldier convict Michael Tobin explained, the deserters had been returned to the colonists by “friendly natives”; that is, Māori who were loyal to the Crown during the New Zealand Wars. Perhaps as a form of insurance, Tobin had also struck Captain Armstrong, his superior. Several other soldiers also used violence against a superior - it was bound to ensure a sentence of transportation, removing them from the theatre of war.

Irish Catholic soldier Richard Shea, for instance, was a private in the 99th Regiment who used his firelock to strike his lieutenant while on parade. This earned him a passage on the Castor to Van Diemen’s Land. His three military companions on the vessel, William Lane, George Morris and John Bailey, all claimed to have been taken by Maori north of Auckland and kept prisoner for four months. But surviving records reveal that their military overlords thought that the three had instead deserted to join the ranks of a rebel chief.

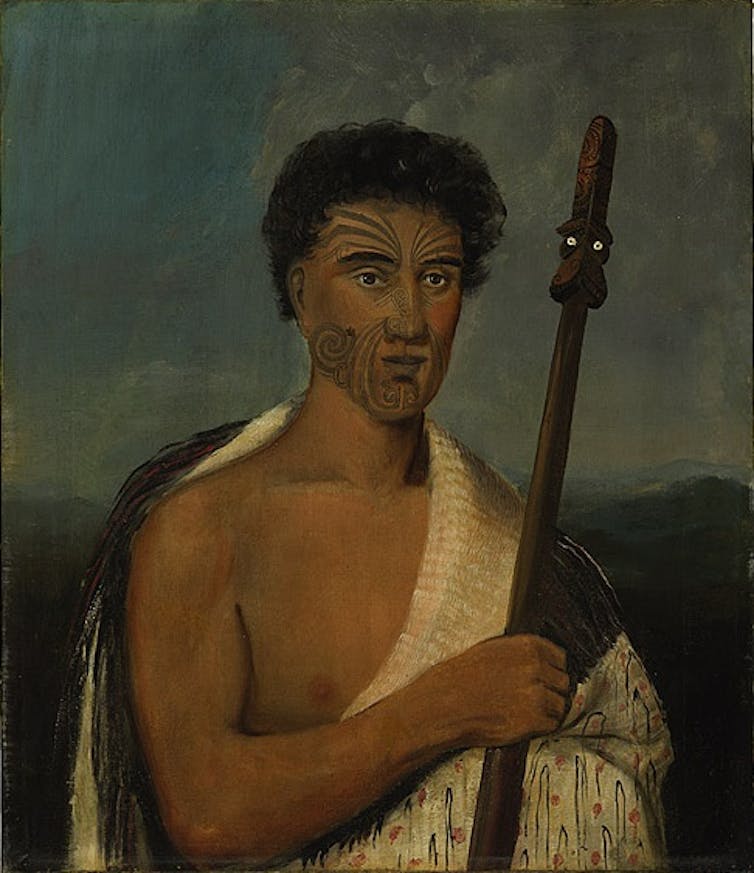

Maori fighters

In 1846, NZ governor George Grey proclaimed martial law across the Wellington region. When several Māori fighters were eventually captured and handed over to colonists by the Crown’s Indigenous allies, they were tried by court martial at Porirua, north of Wellington.

After being found guilty of charges that included being in open rebellion against Queen and country, five were sentenced to transportation for life in Van Diemen’s Land. The traditionally-clothed Māori attracted a lot of attention in Hobart, where colonists loudly disapproved of their New Zealand neighbours’ treatment of Indigenous people. This is ironic given the Tasmanians’ own near-genocidal war against Aboriginal people.

Grey had wanted the Māori warriors sent to Norfolk Island or Port Arthur and hoped they would write letters to their allies at home describing how harshly they were being treated. Instead, they were initially held in Hobart, where they were visited by media and other well-wishers. Colonial artist John Skinner Prout painted translucent watercolour portraits of them. Each of the fighters used pencil to sign his name to his likeness. William Duke created a portrait of Te Umuroa in oils.

Hobartians were worried that the Māori could become contaminated through contact with other convicts. Arrangements were made to send them to Maria Island off the island’s east coast, where they could live separately from the other convicts.

John Jennings Imrie, a man who previously lived in New Zealand and knew some Māori language, became their overseer. Their lives in captivity were as gentle as possible and involved Bible study, vegetable gardening, nature walks and hunting.

Following lobbying from Tasmanian colonists and a pardon from Britain, four of the men, Te Kūmete, Te Waretiti, Matiu Tikiahi, Te Rāhui, were sent home in 1848. Te Umuroa died in custody at the Maria Island probation station in July 1847. It was not until 1988 that his remains were repatriated to New Zealand.

Reducing crime through imposing exemplary sentences saw dozens of working-class men transported to Van Diemen’s Land. One such fellow was James Beckett, a sausage-seller transported for theft for seven years. The only woman sent from New Zealand, Margaret Reardon, was sentenced to seven years’ transportation for perjuring herself trying to protect her partner (and possibly herself) from murder charges. After being found guilty of murdering Lieutenant Robert Snow on Auckland’s North Shore in 1847, the following year Reardon’s former lover Joseph Burns became the first white man judicially executed in New Zealand.

At one stage, Reardon was sent to the Female Factory at Cascades on Hobart’s outskirts to be punished for a transgression. Eventually, she remarried and moved to Victoria where she died in old age.

In 1853, transportation to Van Diemen’s Land formally ended. New Zealand then had to upgrade its flimsy gaols so criminals could be punished within its own borders.