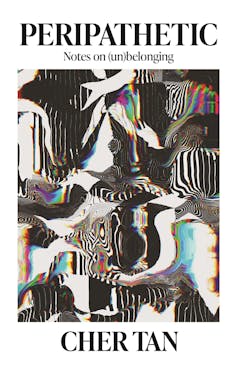

In her debut essay collection, Peripathetic: Notes on (un)belonging, Cher Tan turns her maverick attention to the possibility and power of resistance. Tan’s essays rise out of a defiant, DIY sensibility and sustain a dissident energy. They examine how meaning, purpose and change can be wrought within – and in opposition to – our digitally networked, late-capitalist world.

The nine essays interlink around identity, technology and counterculture. They investigate topics such as internet culture (“Speed Tests”), precarious work (“Shit Jobs”), weirdness (“Who’s Your Normie?”), punk and DIY cultures (“The Lifestyle Church”) and the work of writing (“This Unskilled Life”).

But to list them this way feels reductive. They are essays of great breadth and ambition, equally about migration, inequality, subversion, survival, how we come to know the things we know, and what we do with that knowledge. As their titles suggest, they also carry a sharp wit and ready humour.

Review: Peripathetic: Notes on (un)belonging – Cher Tan (New South)

Tan is one of a new generation of Australian essayists, including Eda Gunaydin (Root and Branch: Essays on Inheritance, 2022), Sally Olds (People Who Lunch: Essays on Work, Leisure & Loose Living, 2022) and Gemma Nisbet (The Things We Live With: Essays on Uncertainty 2023).

These essay collections investigate a central concept in associative and digressive ways. In each, the sequence of essays might not form a linear narrative, but the writer’s sensibility, voice and life experiences unites them into a whole.

Unbelonging, restlessness and digital life

Peripathetic is subtitled “Notes on (un)belonging”. “Notes” suggests direct communication: thoughts and ideas captured in the moment. It also suggests a more physical or tactile text, and Tan uses techniques such as fragmentation, footnotes and blacked-out, redacted text to subtly distinguish each essay.

Thematically, “(un)belonging” suggests restlessness. Belonging is a slippery concept, always in dialogue with its opposite. In the opening essay, “Is this Real?”, Tan tracks the ideal of a cohesive self across physical and virtual realms. There is no longer a stark divide between what’s considered real and digital life, as Tan describes:

You can now be anyone and anything and yet still be yourself. IRL feeds into URL into IRL and over and over again. A GIF of a snake eating its own tail.

Like the endlessly cycling motion of a GIF, the essays in Peripathetic move deftly between life writing and critique. They wield incisive humour and references that span from high theory to niche DIY publications. In a 2018 piece published by Meanjin, On Writing, Tan expressed her commitment to putting her ideas in conversation with other thinkers. With characteristic directness, she explained: “I write to cite”.

Tan makes connections across literature, film, music, cultural theory, philosophy and internet culture. Each reference appears for just long enough for the relevance to spark, before the essay accelerates onwards. It’s a style that challenges the reader to follow extensive maps of influence and resonance.

From Peripathetic, you could compile excellent reading lists for anyone seeking to investigate contemporary cultural theory (Lauren Berlant, author of Cruel Optimism, Sianne Ngai, who specialises in aesthetics and affect theory, philosopher Byung-Chul Han, time activist Jenny Odell), or punk and underground literature (Virginie Despentes, Lisa Carver, Ian Svenenious), or any other of the many genres the essays connect to.

This is especially notable for the fact Tan has not, as she points out, had a tertiary education. Instead, she has wrought her knowledge by DIY methods, driven by her intense critical curiosity.

References zig-zag between high and low, canonical and ephemeral. In “Shit Jobs”, for example, Tan profiles a selection of low-pay, high-precarity jobs she has worked, ascribing them tongue-in-cheek aspirational titles (victualler’s assistant, information input specialist).

In the first few pages, she cites sources as various as radical anthropologist David Graeber (author of Bullshit Jobs), activist texts published by the anarchist CrimethInc. collective, and Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s influential investigation of globalisation, capitalism, and the matsutake mushroom, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins.

‘I learnt I could do anything’

In the central essay of the collection, “The Lifestyle Church”, Tan traces her upbringing through DIY music scenes, first in Singapore, and then to Australia (Kaurna country/Adelaide, then Naarm/Melbourne), where she has lived since 2012. The essay is structured as a series of vignettes that loosely follow the chronology of Tan’s “protracted adolescence”, as she embraces, and is embraced by, the punk and extreme music scene in 2000s Singapore.

Underground music was a method of escape from the repressions of an illiberal democracy which, as Tan describes metaphorically, “prided itself on manufacturing drones”. As she became more involved in the scene, she observed how the stakes were higher in Asia than for equivalent bands in Western countries.

Some of us really wanted to smash imperialism. It wasn’t just a slogan. Writing and singing songs about it was our way of wanting to actualise it, scream it into existence.

Involvement in this scene was an outlet for anger and an expression of rebellion, but it was also an education. “It was where I learnt I could do anything,” Tan writes. She lists some of these skills:

critical thinking, hand-sewing my own rips, being comfortable performing on a stage, navigating cultural differences, dealing with conflict, self-publishing, consent, standing up for my rights, sharing within your means, changing my own bicycle tire, abolitionist politics, planning a timeline, organising events, making things work with little to no money.

This subcultural path and the skills it enabled was a revelatory experience and a life-defining one. Although it was so formative, Tan is careful not to slip into an uncritical nostalgia. “I read punk memoirs and think, am I going to sound like this, a wet rag continually bemoaning the underground’s recurring demise?” She doesn’t – far from it.

Tan’s experiences of racism and sexism, and her observations of the scene’s gradual commodification, gentrification and dispersal work against any suggestion of it being a utopian space. It is testament to Tan’s skill as a writer that she holds these contradictions while ultimately honouring the power of DIY culture.

As much as Tan can be thought of as part of a new generation of essayists, she is also one of a growing number of authors who have developed and continue to pursue their craft through zines and subversive publishing. Australian writers such as Anwen Crawford, Max Easton, Bastian Fox Phelan, and Safdar Ahmed all publish in both traditional literary and DIY formats. It is heartening to see local publishers recognising the power of literature that has been forged through alternative and subcultural pathways.

As a writer who also discovered my voice through punk, DIY and zine culture, there is much in Peripathetic I recognise and admire. Tan’s collection is an important document of DIY sensibility, generous and rigorous in its sharing of life experience, critical thought and networks of influence. Tan’s distinct, direct voice conveys to us the insight that can come about through the powers of dissent and a curious, restless creative mind.