Paid to play, travelling internationally and enjoying celebrity status: the lifestyle of a modern elite professional sportsperson, but also that of some elite sportsmen in ancient Greece and Rome.

Ancient Greeks lived in perhaps 1,000 autonomous communities stretching, in modern terms, from Spain in the west to Afghanistan in the east, from Ukraine in the north to Egypt in the south. Many of these settlements held regular festivals which combined religious celebration with athletic events, especially discus and javelin throwing, running, wrestling and chariot racing.

There were hundreds of festivals, sufficient for circuits to develop in which athletes could participate in local festivals as well as one of the more significant events, such as those held at Olympia. The athletes travelled to participate because they made money. There was no word for amateur in the Ancient Greek sporting lexicon and virtually all elite performers were professionals.

Some were full time athletes, but all competed for prizes. The victor in the footrace at the Panathenaic Games won 100 amphoras of olive oil, the sale of which could have bought half a dozen slaves.

Talented athletes were sponsored by civic benefactors and city authorities and the more successful – who brought renown to their city – gained public pensions after they retired from competitive sport.

So keen were some cities to gain victories, that they persuaded star performers to change their citizenship. The most successful athletes (like Theagenes of Thasos who allegedly won over 1,000 times) had odes commissioned and statues erected to commemorate their feats.

Winning athletes also “unionised”, forming an international association to defend their interests in regard to rights and rewards.

Ancient chariot racers

Roman chariot racing was an organised international business, with charioteers drawn from across the empire. Horses were bred in private and imperial studs in Spain, Sicily, Thessaly, North Africa and Turkey.

By the fourth century, Rome itself held 63 race days a year, each with 24 races, often with crowds of over 100,000 spectators. Staging chariot races was the responsibility of four racing factions which were business entities from at least the first century BC.

Initially the faction managers were private entrepreneurs, but from the late third century, they were run by professional managers. Promoters of a race meeting would provide substantial prize money and pay the factions for supplying entries and drivers.

Charioteers received fees and – even for those who were slaves – a percentage of any prize money. At the extreme end of the earnings spectrum was Spanish charioteer, Gaius Appuleius Diocles, who won 1,462 of his 4,257 races over a 24-year career. Like some star Greek athletes, he went where the money was and over his career raced for all four factions. Others ventured out of Rome to race at the dozens of circuses throughout the empire.

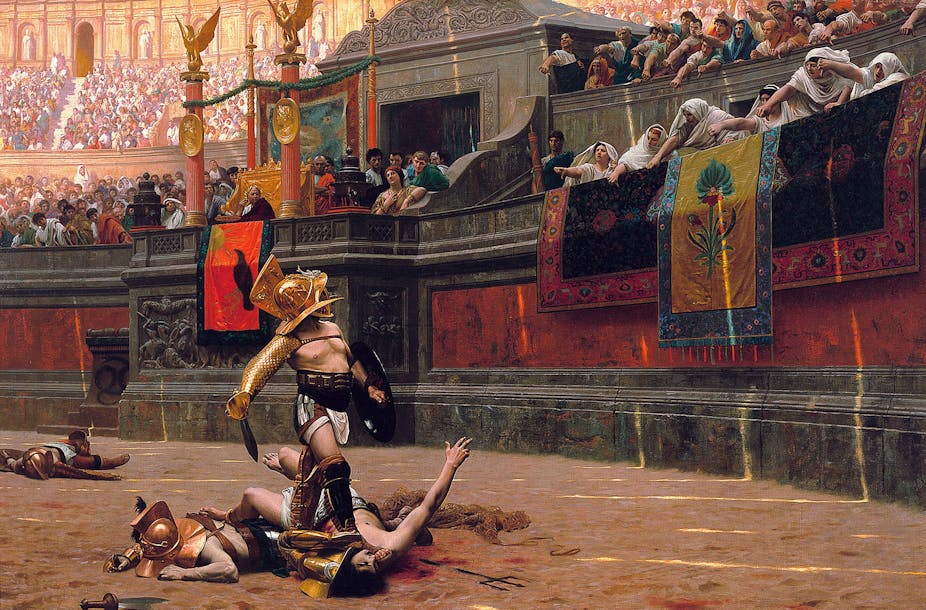

Ancient Roman gladiators

Roman gladiators were highly trained, skilled, professional sportsmen, though generally, they were not free citizens, but condemned criminals, prisoners of war, or slaves. Their career structure was based on a ranking system.

The sportsmen used stage names and practised overt showmanship, gaining followers who identified them in gladiatorial graffiti. Gladiators belonged to establishments of fighters whose managers hired them out to promoters who organised combats. These promoters paid a hiring fee which was between 10% and 20% of the gladiator’s value, but had to pay the full cost if he was killed or seriously wounded.

As well as being housed and fed by the stable manager, win or lose all gladiators were entitled to 20% of their hiring fee and often obtained a share of prize money awarded. They could also receive presents from fans or gamblers.

At least 300 amphitheatres around the Mediterranean area hosted gladiatorial fights. Until the first century, these combats were usually small scale affairs but by the second century some of the contests involved hundreds of pairs of gladiators fighting over several days or even weeks.

Read more: Were there gladiators in Roman Britain? An expert reviews the evidence

Combats did not take the form of sacrifices or executions, but dramatic contests, usually lasting 10 to 15 minutes. They appealed to audiences in part because they were carefully thought out contests that demanded skill and training.

Death was always a possibility, but combat was controlled by referees. Fighters were able to submit and ask for mercy. As fatalities would prove expensive for promoters, fewer gladiators were killed than “thumbs down” mythology suggests.

A few exceptional characters fought over 50 times, though most top-ranked gladiators participated in less than 20 combats. For this latter group career earnings were less than two year’s wages for an unskilled worker, scant reward for risking life and limb, but sufficient perhaps to buy freedom.