Welcome to our State of the Nation series. These pieces will provide a clear-eyed health check on the coalition government’s progress over the past five years, across a range of vital policy areas. Today, David Bell, former chief inspector of schools and permanent secretary at the Department for Education, looks at the legacy of the coalition’s school and university reforms.

I have been often asked about the part I played, as the then-permanent secretary at the Department for Education, in the weekend after the 2010 general election, as the coalition negotiations began.

To which I can only answer truthfully: I went home and mowed the lawn.

It seems naïve now, but few in the civil service had thought a full Tory-Liberal Democrat coalition possible. Certainly nobody believed it would last for five years. This time Whitehall will be prepared for all eventualities. Our political system is fracturing. And that means party manifestos will be the starting points for negotiation, not necessarily agendas for government.

Five years ago, many thought the outcome of those “five days in May” would result in timid government. Yet the pace of legislation and changes in education, in particular, have disproved forever the warnings that coalition government leads to paralysis.

Fast-paced education reforms

But in trying to judge the long-term impact of the changes in schools and higher education, I am reminded of the oft-misquoted quip by the Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, when asked about the impact of the French Revolution: “It’s too early to say”.

For the biggest societal, political and economic reforms do not fit into neat five-year electoral cycles. They take decades. And what feels like a seismic shift in the short term, may merely be a footnote in the long run.

One widely held view is that the coalition has led radical change in education. You can see why. Thousands of new academies – more than 4,500 in March 2015. Hundreds of new free schools – 254 open with many more due to launch in September. A new inspection regime. A complete overhaul of qualifications, tests and the national curriculum. New targets and league tables. A restructured school building programme. A new funding system. Performance-related pay. Pensions reform.

And in universities, “shock therapy” to open up the student market. Tuition fees trebled. The funding system totally overhauled. Student number caps abolished. Public funding cut. Barriers to private sector provision removed.

More of the same

An alternative reading of the past five years, however, is that all these reforms are no more than a logical extension of existing policies.

In schools, one can draw a more or less straight line from the Conservatives’ “Great” Education Act of 1988 onwards. More and more power has been devolved to schools from local authorities, there has been a push for greater transparency and accountability through league tables and schools inspectorate Ofsted, and parents given a greater choice.

In higher education, “marketisation” could be said to build on the huge expansion in university numbers, when the old polytechnics were given degree-awarding powers in 1992. And the principle that students should share the financial burden of undertaking a university education was introduced in the late 1990s by Tony Blair’s first administration.

Set up to fail?

But yet another, third reading, is that the coalition’s urgency to reform has unwittingly set the system up to fail in the coming years.

In schools, overhauling exams at 16 and 18 in parallel might well end in tears – an experiment conducted with thousands of schools and hundreds of thousands of pupils, that we do not actually know will work. The lesson from the first year after GCSEs replaced the old O-levels in 1988, and the current model of A-levels were introduced in 2002, is that major reforms always have unexpected consequences.

Or in higher education, there is a huge concern that the current changes will risk the financial situation of at least some of our 150 universities. In a market not everyone can be a winner. Some in the university sector are worried that the result of creating a system based on student demand, at a time of ever tighter public finances, is that some institutions will start to wither and – who knows – eventually collapse.

Will all or any of these changes work? It is simply too early to say, despite the mudflinging at ministers this week from a succession of teacher union conferences. We are only just about able to assess the impact of the previous Labour government’s schools reforms, including the London Challenge, City Academies and Sure Start. This summer’s A-level cohort are the living embodiment of “Blair’s generation” having been born in 1997 – but it will take 20 to 30 years to properly understand whether they are truly socially mobile.

No evidence yet of impact

A more sensible approach then is to divorce policy analysis from electoral cycles.

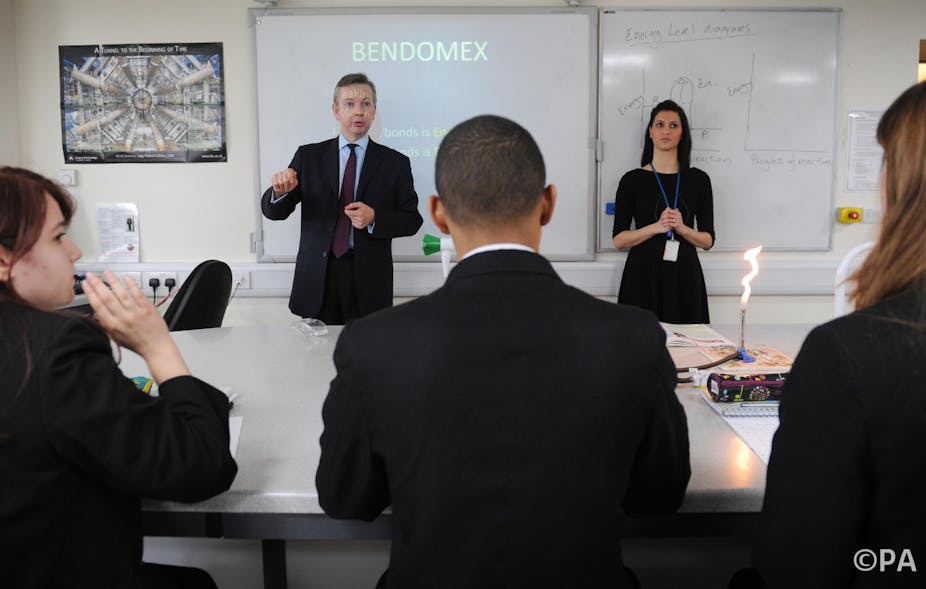

Love them or loathe them, former secretary of education Michael Gove and higher education minister David Willetts came into government with a clear vision and agenda for schools and universities respectively. And both, arguably, were jettisoned from their ministerial posts last year because their reforms had longer trajectories than the next polling day. Whatever you think of what they were trying to do, they were both focused on long-term legacy and delivery, not necessarily winning votes in the short term.

One can see the problem with this in how the current government is now presenting its education achievements to the electorate. For while ministers can reel off lists of new academies and free schools, they cannot yet point to clear evidence that any of it has had a tangible impact.

This leads to a slightly perverse situation where ministers simultaneously welcome a drop in national five A* to C GCSE results as a sign of tougher standards; hail 250,000 fewer children being taught in underperforming schools; and welcome more pupils studying history, geography and languages.

They have based all three of these boasts on children who took exams in an system they regard as flawed and not fit for purpose.

As Brian Lightman, the general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL) told his annual conference this month: “we do not know how well our system is performing … and may not for some years to come.” A bizarre situation to be in.

An end to ministerial tinkering

That is why I and others have been putting forward ideas to “depoliticise” education policy – keeping ministers accountable but giving the system long-term stability and consistency.

A moratorium for the next parliament on new legislation and major structural changes. Slimming down the DfE’s remit to focus on overall strategy, not day-to-day management of schools. A permanent, independent commission to steer curriculum and assessment, looking ahead ten to 20 years – not five. A cross-party backed review on university funding and structure, to create consensus on how to strengthen and sustain higher education in the long-term.

The new secretary of state for education, Nicky Morgan, told the same ASCL conference that:

What children learn in schools must be something that is decided by democratically elected representatives.

As permanent secretary, I might have agreed but my view now is that the way Whitehall “does” policy is outdated. How accountable can governments be, if constant change means the public is never a position to judge their performance fairly?

So it is time for the politicians to be brave. There is something in the air in Westminster which compels ministers to meddle, to act as commentators not leaders, to be driven by short-term political tactics not long-term strategy. It even makes some ministers feel the need to sit in their offices drafting curricula and syllabi. Teaching practice, knowledge and skills evolve faster and more organically than remote, monolithic government departments can possibly direct.

So my plea for the next set of ministers is not to go back to square one after the election. Education and skills are as much part of our national infrastructure as transport, energy, industry and urban regeneration – all requiring serious long-term planning. If we can set up an independent inquiry to look coolly and rationally at runway capacity in the south of England, then we can surely do likewise with our nation’s curriculum and examination system. We need to base policy decisions on clear, hard-headed evidence, data and analysis not ministerial whims.

An education system without the short-term politics: that would be a revolution worth waiting for.