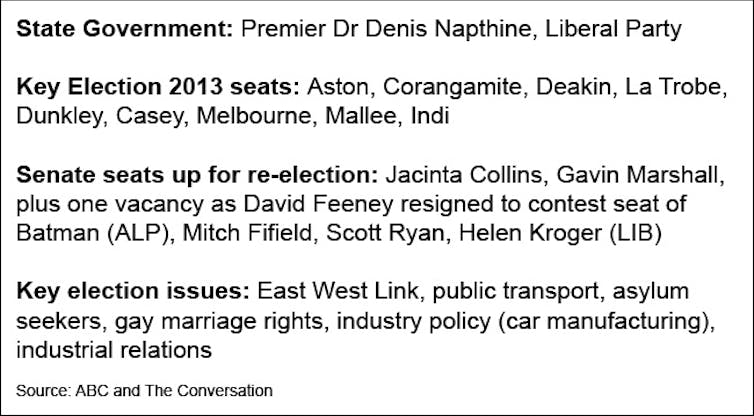

STATE OF THE STATES: a snapshot of the key issues affecting each state and territory in the lead up to Saturday’s election.

With a total of 37 seats, the state of Victoria should figure as a major battleground in federal elections. The reality, however, is that the second-largest state in the Commonwealth (in terms of population) tends to be bypassed in national election campaigns for the simple reason that, for all the divisions it has, Victoria has comparatively few marginal seats.

Ahead of the 2013 election, only three divisions are held with a margin of less than 1%: the Labor seats of Corangamite on 0.3%, Deakin on 0.6%, and the Liberal seat of Aston on 0.7%. Only another three seats have margins between 1% and 2%: the Labor seat of La Trobe, on 1.7%, and the Liberal divisions of Dunkley on 1.0% and Casey on 1.9%. That’s a total of six seats or 16% of the total number of Victorian seats.

Even if the benchmark for what constitutes an ultra-marginal seat is extended to 5% or less, only one other seat – the Liberal seat of McMillan on 4.2% – would come in to consideration. Few pundits consider McMillan to be winnable for Labor, however, as the polls indicate that no Liberal marginals are at risk.

Seats to watch

In amongst this two-party contest are three other interesting battles.

The first is in the previously safe Labor division of Melbourne, currently held by the sole Greens MP Adam Bandt, who created history by winning the seat in 2010. Given that his Labor competitor Cath Bowtell polled a slightly higher primary vote, being preferred ahead of Labor on the Liberal Party how-to-vote card was the critical element to the contest that got Bandt over the line in 2010.

However, the Liberal Party has indicated that in 2013 their preferences will be directed to Labor ahead of the Greens, which makes Bandt’s chance of being returned dependent on his ability to win a much larger share of the primary vote in this election. Pundit forecasts of what he would need vary between 42% to 45%, and Bandt’s state-based colleagues were unable to breach the 40% mark in the 2010 state election, nor in the 2012 by-election for the state seat of Melbourne.

The contest for the seat of Mallee in the far north-western rural corner of the state is the second interesting battle. Mallee has historically been a very safe National party seat, but the retirement of sitting National John Forrest has opened the seat to competition from both Labor and Liberal parties.

Despite the urgings of federal Liberal leader Tony Abbott for Nationals candidate and former Victorian Farmers Federation president Andrew Broad to contest this seat as the lone Coalition representative, the Victorian Liberals have nominated Chris Crewther. Labor has promised to direct preferences to the Liberal candidate, allegedly as part of a deal to secure Liberal preferences for Labor in Melbourne.

The anger of local Nationals is said to be so great that it is spilling over in to nearby Indi, the third interesting contest. Indi is currently held by Liberal Sophie Mirabella who does not have to worry about a National Party candidate, thanks to the Coalition agreement.

Mirabella’s problem, however, appears to be that an independent candidate (Cathy McGowan) enjoys quite strong local support. McGowan will also be assisted by promises of preferences directed by both Labor and the Greens. Indi is shaping up as an intriguing contest.

These three seats aside, the outcome of the two-party contest in Victoria will only be significant if the overall result is close. Opinion poll data is suggesting a two-party swing against Labor of 3% to 4% which would probably account for losing Corangamite, Deakin and La Trobe. The swing against Labor can be partly attributed to what happened in 2010, when Labor’s state-wide two-party vote of nearly 55% was an historic high.

The Senate, meanwhile, looms as a complicated battle field. Victoria is a strong state for the Greens, and the party should secure a Senate position at this election. Labor would definitely get at least one seat, but a second seat might be difficult to secure were the Labor primary vote to fall below 29%. The Liberal-National joint ticket can be assured of wining two seats, but a third seat might be out of the question with a primary vote in the low 30s.

The sheer number of minor parties running for the Senate is the problem for the major parties here, as each has the potential to take primary vote away from the major parties. The sixth seat in Victoria looks like being a battle between the Labor Party, the Liberal Party and a right-of-centre minor party (most likely Family First).

Snapshot of Victoria

Key issues

The peculiarities of the Victorian contribution to the national contest reflect the key features of the state’s human geography. Victoria is a state in which 75% of voters are in metropolitan seats. This leaves rural districts very safe for the non-Labor parties.

The metropolis, meanwhile, is a class-divided city, with partisan Labor voters clustered in the northern and western suburbs (spreading out to the provincial cities of Ballarat, Bendigo and Geelong and impacting on their voting alignments) and concentrated around Dandenong in the outer south-eastern suburbs.

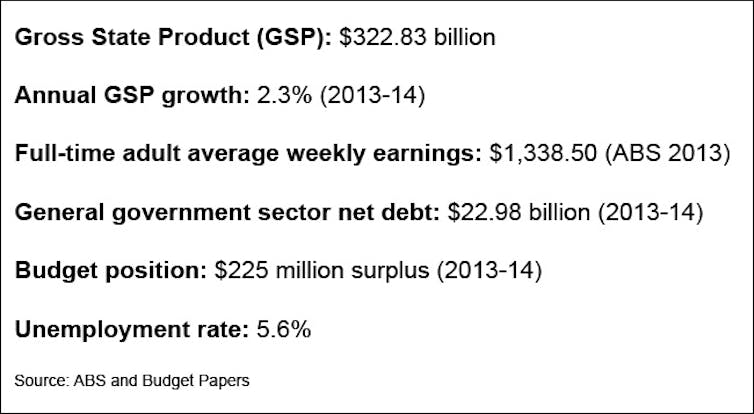

These districts are also where Melbourne’s light and heavy industry, food processing plants, freight transport hubs and Australia’s largest shipping port are to be found. Economic policy, industry policy and industrial relations are key issues in these seats and few voters are attracted to the Liberal party’s approach.

Partisan Liberal voters meanwhile are concentrated in the affluent suburbs along the eastern banks of the Yarra River and the inner south-eastern bay-side suburbs of Brighton and Sandringham. Voters in these seats would be as equally resistant to Labor’s message, although it is true that this electorate can display support for socially progressive ideas.

This is the sort of Liberal electorate that might be a bit uneasy with some of Tony Abbott’s reputed social conservatism. This unease is probably confined to the Liberal branches in these areas, however. Expect big swings to the Liberals in the party’s electoral heartland.

Meanwhile, at the very centre of the metropolis is a Green enclave, dominated by a concentration of younger, highly educated, single, professional voters. These voters place issues such as gender equality, gay marriage rights, accommodation of asylum seekers and other such social progressive issues ahead of more economic and wealth redistribution concerns that can be found in the other districts.

Although Tony Abbott and Kevin Rudd have visited the three ultra-marginal seats, the notion that the national campaign has bypassed Victoria is as strong as it was in previous federal elections. Victoria doesn’t offer the major party leaders a great deal. There are few swinging seats, and even the partisan voters can give their preferred parties and their leaders a hard time in the policy debate.

Victoria is a strident sort of place – the product, presumably, of an electorate in which 80% of the lower house seats are safe for the three main parties.

This is the fourth article in our State of the states series. Stay tuned for the other instalments in the lead up to Saturday’s election.

Part one: Tasmania

Part two: Northern Territory

Part three: Western Australia

Part five: South Australia

Part six: Australian Capital Territory

Part seven: Queensland

Part eight: New South Wales