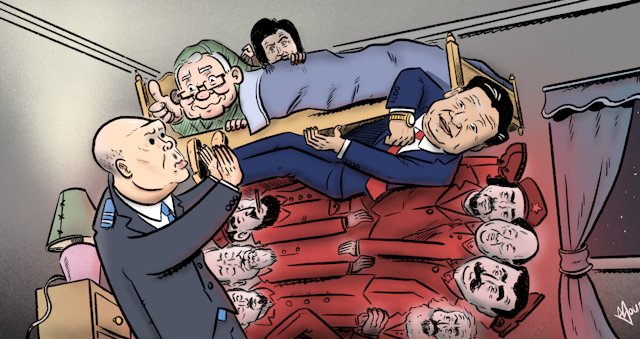

The Reds are back. Scott Morrison’s Liberal-National government has recently launched an offensive of “red-baiting”, a practice long thought consigned to the history books, in preparation for an anticipated May 2022 election.

Last November, Defence Minister Peter Dutton hounded Shadow Foreign Affairs Minister Penny Wong, charging her with “not standing up for [Australian] values” in comments on the China-Taiwan dispute.

This week, News Corp has targeted Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese after the Chinese Global Times offered him some backhanded compliments. A video also emerged of Albanese speaking Mandarin at an economic summit, and he was found to have participated in a forum for Tribune, newspaper of the defunct Communist Party of Australia. (This interview, it should be noted, was 31 years ago.)

Such claims have long plagued the progressive side of politics. Since the first news of the Bolshevik victory in the 1917 Russian Revolution reached our shores, fears of Australia following Vladimir Lenin’s lead have been used and abused by conservative politicians for electoral gain.

But, how successful have these “moral panics” been? And do they still pass muster with today’s electorate?

Read more: 'National security' once meant more than just conjuring up threats beyond our borders

A canker that must be cut out of our national life

The Communist Party of Australia was founded in October 1920 by a mix of Marxists, anarchists, feminists and trade unionists. Inspired by events in Russia, where the working class had seized power, they wanted world revolution. But, following Lenin’s theories, they also saw parliamentary representation as a way to politicise the working class.

Aside from Fred Paterson, an Oxford-educated communist lawyer who represented the seat of Bowen in the Queensland Parliament from 1944 to 1950, the party’s threat was not at the ballot box. Instead, the Australian Labor Party faced accusations of insufficient loyalty, or being knowing dupes of Moscow.

In 1925, when the Communist Party had only a few hundred members, the prime minister, Stanley Bruce, first used the communist bogey to electoral effect. A wave of industrial unrest was blamed on the work of “a few extremists” in the trade unions, and “political labor”, Bruce argued, was “afraid of the strength and power of those who control those organisations”. He declared:

“[T]he only manner in which citizens of Australia can declare their attitude is at the poll. […] the canker of these men advocating Communistic doctrines must be cut out of our national life”.

Bruce, a staunch defender of White Australia, used the communists’ internationalism against Labor. Communist officials in the recently founded Australian Council of Trade Unions had affiliated it to the Soviet-aligned Pan Pacific Trade Union, which included organisations in China and Japan.

The pro-Bruce Daily Telegraph presented this as evidence the Labor Party, by extension, was soft on immigration restriction. The mud stuck and Labor lost six seats in the 1925 election.

The Labor Party did not take these attacks lying down. The New South Wales branch had banned “dual membership” in 1924. But such actions proved insufficient. Historians credit this “leftist bogey” with keeping Labor out of government – bar a brief spell during the Great Depression – until 1940.

An alien and destructive pest

The 1940s were the heyday of Australian Communism. A wave of popular enthusiasm for the Soviet Union’s wartime accomplishments saw the party grow from 4,000 members in 1941 to over 20,000 three years later. Communists gained control of trade unions representing over half of Australian workers, and formed an alliance with the wartime Labor government of John Curtin.

A directive from Moscow that communists should launch an industrial offensive quickly made this wartime relationship an electoral liability for Labor. In 1946, at the helm of the recently formed Liberal Party, Robert Menzies blamed everything from fuel shortages to housewives’ difficulties finding essential items and trade relations with Malaya on

“the Government’s supine surrender to a minority of Communists and agitators”.

While Curtin’s successor, Ben Chifley, used wartime clout to win that contest, the 1949 election occurred only two months after Mao’s communists proclaimed the People’s Republic of China. This mixture of the “yellow peril” with communism, along with major disruption caused by a communist strike in the coal industry, delivered Menzies a handsome win. The Liberals received a 5% swing and a stunning 48 seats. He declared communism “an alien and destructive pest” and promised: “If elected, we shall outlaw it.”

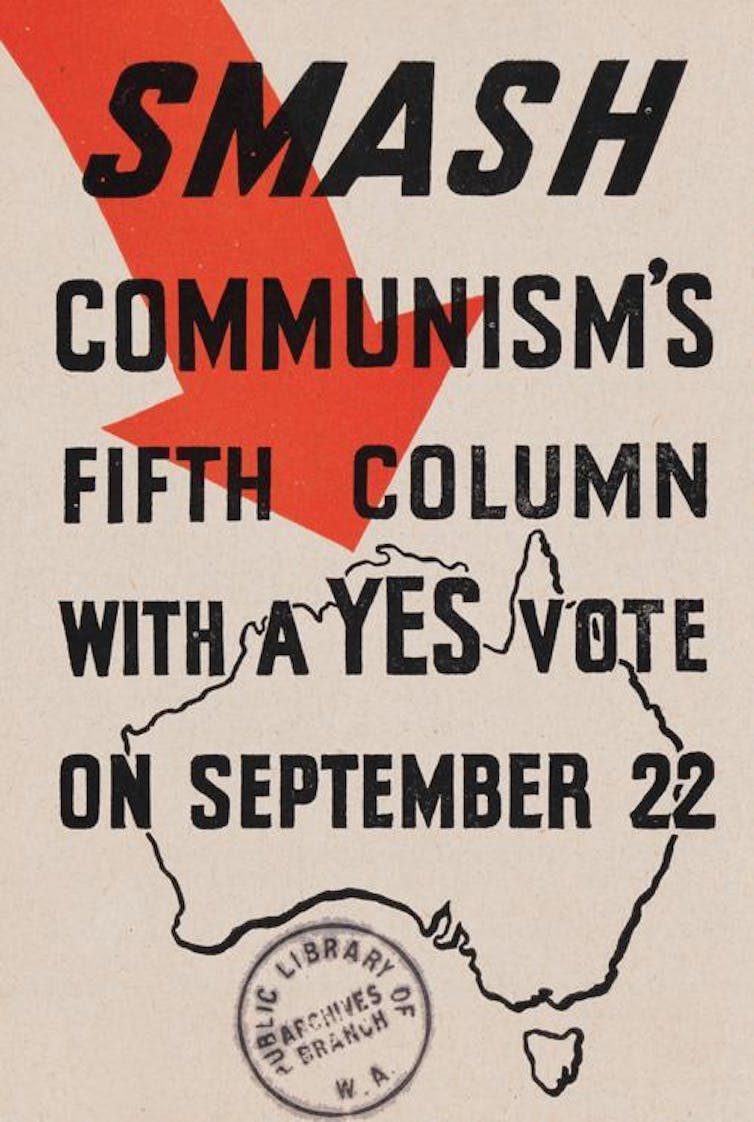

Communist ranks were decimated in these years, but with the support of Labor leader H.V. Evatt, the Communist Party was able to narrowly defeat Menzies’ attempt to ban it. This result owed more to fears of what such a ban might mean for democracy than the electorate’s support for communist ideals.

Where do you draw the line?

This was seen as collusion by by some in Evatt’s own ranks. Labor had established trade union “industrial groups” to undermine communist control in the late 1940s and these hosted a right-wing, Catholic opposition. Headed by B.A. Santamaria, this opposition used revelations at the Royal Commmission on Espionage, sparked by the defection of Soviet diplomat Vladimir Petrov, as ammunition to split the Labor Party.

Originally called the Labor Party (Anti-Communist), the Democratic Labor Party’s raison d'etre was red-baiting, and it kept Labor out of office for a decade and a half.

Conservatives found one tool particularly useful in these years: stoking fears of national liberation movements in Asia, presented as an extension of the communist menace. A prominent Liberal party campaign poster from the 1966 election pictured arrows menacingly pointing through South-East Asia towards Australia, asking voters: “Where do you draw the line against Communist aggression?”

In the late 1960s, however, the local communist party had broken with the Soviet Union, and the Cold War entered a period of detente. Labor Opposition Leader Gough Whitlam visited China in 1971, and Liberal Prime Minister William McMahon’s anti-communist fulminations fell flat when US President Richard Nixon announced similar plans only weeks later.

In 1983, prime ministerial aspirant Bob Hawke memorably saw off Malcolm Fraser’s suggestion voters should hide their money under the bed in the event of a Labor win by declaring:

You can’t keep your money under the bed – that’s where the commies are!

What had once been a tragedy for Labor seemed now only farce.

McCarthyism, 21st-century style

The hiatus of red-baiting as an effective tactic in the 1980s – arguably replaced by fears of refugees and terrorists – begs the question: why is it back today?

The rise of China from Cold War isolation to global superpower is one answer. Another can be found in the weaponising of far-right language about “cultural Marxism” from the United States.

Read more: Is 'cultural Marxism' really taking over universities? I crunched some numbers to find out

But will it be effective? A 2007 campaign to tar Julia Gillard as a communist failed to keep Labor out of office, and it is unclear who the market for this rhetoric is today.

Australians under 40 have no living memory of the Cold War and are more open to socialist ideas after the Global Financial Crisis.

Furthermore: there is no dangerous “fifth column” on which to hang fears. The Communist Party of Australia wound up in 1991. And Chinese-Australians – whom government members have targeted in a McCarthyist fashion over imagined Communist Party links – tend to skew conservative.

Lastly, given there is no notable difference between Labor and Liberal on foreign policy towards China, the chances of mud sticking seem limited. We can only hope that 2022 – almost a century after its first usage – marks the end of red-baiting in Australian politics.

Correction: this article originally read “In 1925, when the Labor Party had only a few hundred members …”. It has been corrected to read “In 1925, when the Communist Party had only a few hundred members …”