Planning a trip to the tropics? You might end up bringing home more than just a tan and a towel.

Our latest research looked at mosquitoes that travel as secret stowaways on flights returning to Australia and New Zealand from popular holiday destinations.

We found mosquito stowaways mostly enter Australia from Southeast Asia, and enter New Zealand from the Pacific Islands. Worse still, most of these stowaways are resistant to a wide range of insecticides, and could spread disease and be difficult to control in their new homes.

Read more: Why naming all our mozzies is important for fighting disease

Secret stowaways

Undetected insects and other small creatures are transported by accident when people travel, and can cause enormous damage when they invade new locations.

Of all stowaway species, few have been as destructive as mosquitoes. Over the past 500 years, mosquitoes such as the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti) and Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) have spread throughout the world’s tropical and subtropical regions.

Dengue spread by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes now affects tens to hundreds of millions of people every year.

Read more: Explainer: what is dengue fever?

Mosquitoes first travelled onboard wooden sailing ships, and now move atop container ships and within aircraft.

Adults in your luggage

You probably won’t see Aedes mosquitoes buzzing about the cabin on your next inbound flight from the tropics. They are usually transported with cargo, either as adults or occasionally as eggs (that can hatch once in contact with water).

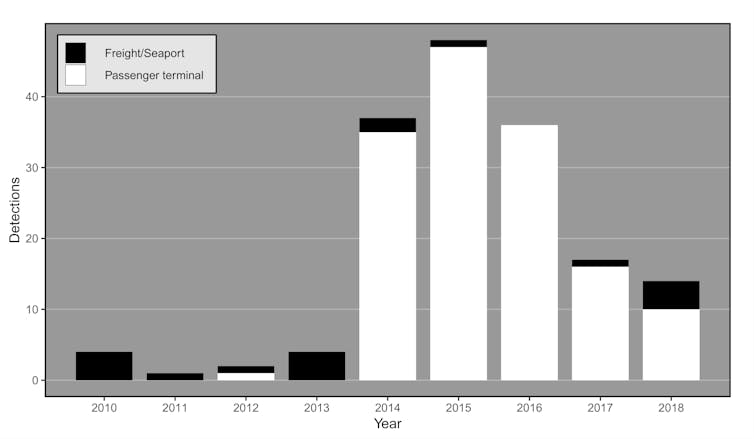

It only takes a few Aedes stowaways to start a new invasion. In Australia, they’ve been caught at international airports and seaports, and in recent years there has been a large increase in detections.

Read more: Curious Kids: When we get bitten by a mosquito, why does it itch so much?

In our new paper, we set out to determine where stowaway Aedes aegypti collected in Australia and New Zealand were coming from. This hasn’t previously been possible.

Usually, mosquitoes are only collected after they have “disembarked” from their boat or plane. Government authorities monitor these stowaways by setting traps around airports or seaports that can capture adult mosquitoes. Using this method alone, they’re not able to tell which plane they came on.

But our approach added another layer: we looked at the DNA of collected mosquitoes. We knew from our previous work that the DNA from any two mosquitoes from the same location (such as Vietnam, for example) would be more similar than the DNA from two mosquitoes from different locations (such as Vietnam and Brazil).

So we built a DNA reference databank of Aedes aegypti collected from around the world, and compared the DNA of the Aedes aegypti stowaways to this reference databank. We could then work out whether a stowaway mosquito came from a particular location.

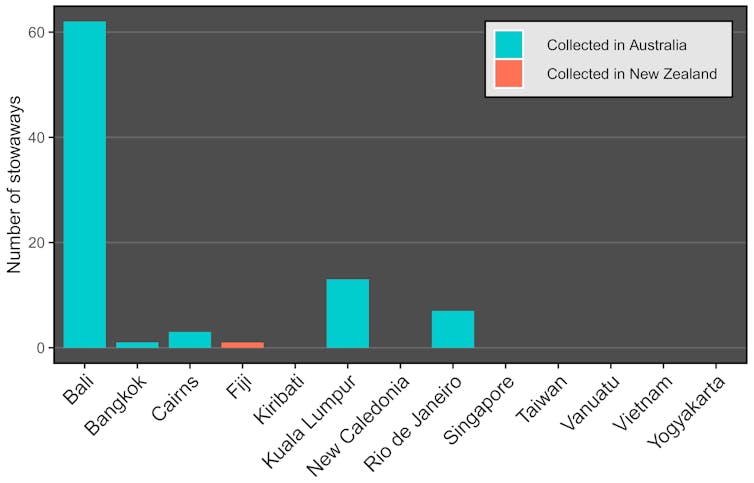

We identified the country of origin of most of the Aedes aegypti stowaways. The majority of these mosquitoes detected in Australia are likely to have come from flights originating in Bali.

Now we can work with these countries to build smarter systems for stopping the movement of stowaways.

As the project continues, we will keep adding new collections of Aedes aegypti to our reference databank. This will make it easier to identify the origin of future stowaways.

New mosquitoes are a problem

As Aedes aegypti has existed in Australia since the 19th century, the value of this research may seem hard to grasp. Why worry about invasions by a species that’s already here? There are two key reasons.

Currently, Aedes aegypti is only found in northern Australia. It is not found in any of Australia’s capital cities where the majority of Australians live. If Aedes aegypti established a population in a capital city, such as Brisbane, there would be more chance of the dengue virus being spread in Australia.

The other key reason is because of insecticide resistance. In places where people use lots of insecticide to control Aedes aegypti, the mosquitoes develop resistance to these chemicals. This resistance generally comes from one or more DNA mutations, which are passed from parents to their offspring.

Read more: The battle against bugs: it's time to end chemical warfare

Importantly, none of these mutations are currently found in Australian Aedes aegpyti. The danger is that mosquitoes from overseas could introduce these resistance mutations into Australian Aedes aegpyti populations. This would make it harder to control them with insecticides if there is a dengue outbreak in the future.

In our study, we found that every Aedes aegpyti stowaway that had come from overseas had at least one insecticide resistance mutation. Most mosquitoes had multiple mutations, which should make them resistant to multiple types of insecticides. Ironically, these include the same types of insecticides used on planes to stop the movement of stowaways.

Other species to watch

We can now start tracking other stowaway species using the same methods. The Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) hasn’t been found on mainland Australia, but has invaded the Torres Strait Islands and may reach the Cape York Peninsula soon.

Worse still, it is even better than Aedes aegypti at stowing away, as Aedes albopictus eggs can handle a wider range of temperatures.

A future invasion of Aedes albopictus could take place through an airport or seaport in any major Australian city. Although it is not as effective as Aedes aegypti at spreading dengue, this mosquito is aggressive and has a painful bite. This has given it the nickname “the barbecue stopper”.

Beyond mosquitoes, our DNA-based approach can also be applied to other pests. This should be particularly important for protecting Australia’s A$45 billion dollar agricultural export market as international movement of people and goods continues to increase.

Read more: Explainer: what is Murray Valley encephalitis virus?