Sally Percival Wood’s new book, DISSENT: The student press in 1960s Australia, takes a look at the people, power and politics of student newspapers in that tumultuous decade. Tension between political conservatism and social unrest in post-war Australia played out on university campuses, turning them into sites of dissent. Percival Wood delves into the history of student newspapers, and their role in transforming Australia socially, culturally and politically.

In 2017, it’s hard to imagine a student newspaper creating any sort of political waves. Fifty years ago, in 1967, things were very different. Student newspapers were bristling with dissent and, increasingly, they agitated the authorities.

In 1967, the academic year began with student newspapers saturated in politics. At the National Union of Australian University Students (NUAUS) summer conference, concerns were expressed about the presence of ASIO agents on university campuses. ASIO, they had reason to suspect, had files on students they regarded as a potential security risk.

The University of Adelaide’s On Dit reported that it had evidence of ASIO activity on campus. Several students involved in the Student Representative Council (SRC) and NUAUS had experienced break-ins at their homes, and some of their files had gone missing.

On Dit also reported that a “prominent right-wing student politician” had been approached about becoming an undergraduate ASIO agent at the university, and a former SRC executive was approached to work for the intelligence agency. The NUAUS also decided at its 1967 conference that it was time it expressed an opinion on the Vietnam War. By then, the war was claiming an increasing number of Australian conscripts, many of whom had just started their university degrees.

In Victoria, the state was gripped with the hanging of Ronald Ryan only a few weeks before the university year commenced. The University of Melbourne’s Farrago took a strong position, calling for Victoria to “move into the 20th century.”

The editors ran a special four-page edition over the summer break — December 1966–January 1967 — fully devoted to the Ryan case. Typical of student newspapers of the day, both sides of the debate, for and against the death penalty, were given equal space to argue their position.

Over at Monash University, the year’s first edition of Lot’s Wife announced “WANTED d.o.a. [dead or alive]”, and featured six sketched portraits of politicians, including Victorian Premier Sir Henry Bolte, with the caption:

Wanted for the premeditated torture and murder of Ronald Ryan.

Prime Minister Harold Holt also appeared under the words:

Wanted for the murder of kidnapped Australian minors; also for complicity in the torture and murder of North Vietnamese citizens.

US president Lyndon B. Johnson was “wanted for the murder of thousands of American citizens; for the torture and murder of North Vietnamese citizens; for suspicion of murder in Dallas, U.S.A. in July 1963” — a contentious reference to the assassination of LBJ’s predecessor, president John F. Kennedy.

Beneath the six portraits were the ominous words “students beware of these men”.

In March 1967, The University of Sydney’s Honi Soit asked on its front page “Asian Commies: are they red or yellow?” The question did not, as it might appear, refer to racial colour. Rather, it questioned the intensity of ideological courage (communist = red) or cowardice (= yellow).

It related to a report on the Orientation Week Symposium “Does Asian Communism Pose a Threat to Us?”, at which every shade of political opinion in Australia was represented. Liberal MP W.C. Wentworth, the secretary of the Communist Party Laurie Aarons, Melbourne University’s ubiquitous Dr Frank Knopfelmacher, and Francis James, who had recently run as a Liberal reform candidate in the 1966 federal election. James was also well known in student press circles as the head of the Anglican Press, printer of Oz and Tharunka both of which were tried for obscenity in 1964.

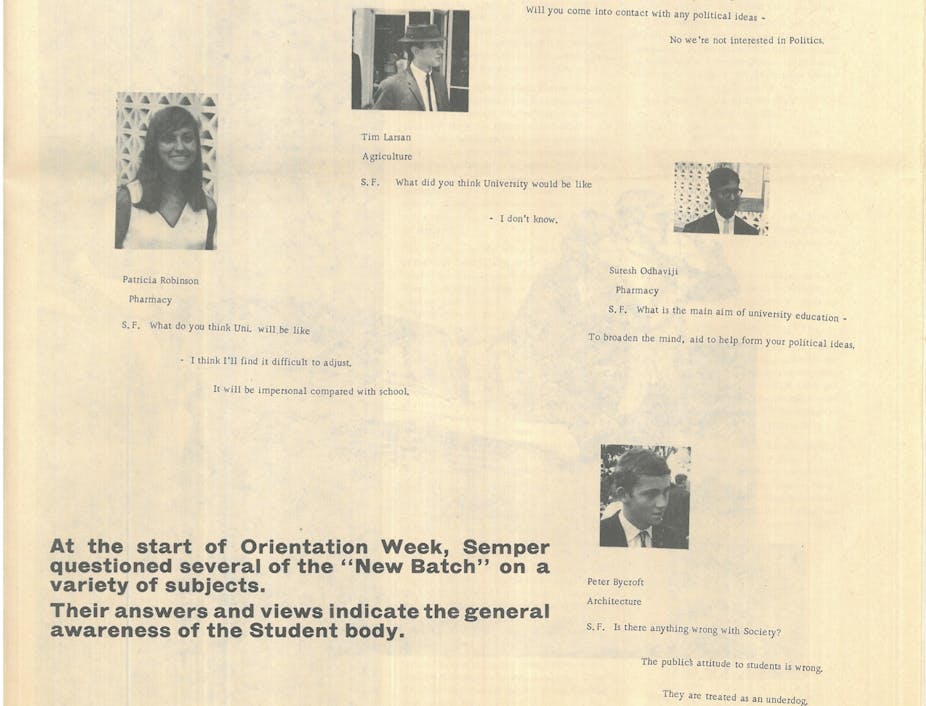

Orientation Week 1967 at The University of Queensland was equally provocative. The year’s first issue of Semper Floreat reprinted O-Week speeches given by two prominent lecturers, Peter Wertheim and Dan O’Neill. In preparing first-year students for university life, both made pessimistic statements about UQ that were reported in Brisbane’s mainstream press. Wertheim expressed despair over the apathy at the university, which was generally seen as “a factory, of well-trained professional cogs produced to keep the wheels of society going”.

But he had observed the sparks of renewal, of students questioning and becoming restive about political issues. He wanted to see this grow and gather cohesion. He said:

A genuine university would have to have a vital university community, composed of staff and students in communion with one another.

Meanwhile, in the nation’s capital, Woroni reported on the ANU’s obvious staff and student “communion” on display that January. It reported demonstrators had seen the behaviour of the NSW anti-demonstration squad for the first time in Canberra.

At the demonstration in question, several ANU students and staff were arrested. The demonstration was held in protest of the visit of South Vietnam’s prime minister Nguyen Cao Ky, who had taken over as prime minister after Ngo Dinh Diem’s assassination.

Over in Perth, UWA students shed some light relief on the 1967 academic year with Pelican’s annual spoof edition for Prosh week. The Prosh Peoples Daily announced: “Independence is Declared: W.A. breaks from east”.

Evoking the time-honoured dream of secession from the eastern states of Australia, it was reported that Western Australia’s “Premier Bland” had made a unilateral declaration on the state’s independence. He announced:

From this time henceforward, we, the government and people of Western Australia, are independent, separate, divorced and entirely disassociated from those filthy slugs in the east.

While students in Perth seemed to be in high spirits as their university year took off, in Tasmania there was gloom and despair over their Orientation Week “flop”. A Togatus observer reported:

Never again must freshers be subjected to the dreary round of speeches and cancelled meetings that were inflicted on them last week.

The front-page report ran through a series of sad sub-headings: “Farce”, “No Sex”, “In a Daze”, and “Boring”, before coming up with “Suggestions”. These included, first, shortening it as spreading it over a week made it tedious.

The second suggestion to brighten up O-Week was disarmingly modest.

Wouldn’t it be a marvellous idea if we could have a real Guided Tour of the University Campus.

Students at the University of New South Wales had a much better solution for brightening up the week for freshers, “bringing Bridget Bardot and Peter Sellers together in Orientation Week — a week of films included two 1960s classics, Bardot in A Very Private Affair and Sellers in The Wrong Arm of the Law.”

It was not all films and fun though. Tharunka also reported that the “most important and valuable” part of O-Week was the number of talks and seminars each day.

The year 1967 began with a healthy dose of political adrenalin, while O-Week 2017 was launched on Prozac. At the University of Sydney, students watched Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory and at Monash University a Summerfest of international food and family fun replaced the radical foment that made Monash the most politically dynamic campus in the country.

DISSENT explores the people, the politics and the power of the student press in 1960s Australia. It traces the birth of the women’s movement and gay rights, the opening up of university education to Aboriginal students, the fight against the Vietnam War and conscription, and the pitched battles over censorship, all of which were waged by the audacious student editors of the 1960s.