The official count of Americans lost to COVID-19 has surpassed 1 million. It is the latest grim milestone that has marked the progression of deaths and infections since the virus took hold in the U.S. in March 2020.

Such numbers make it hard to memorialize individuals – a problem that has existed throughout the ages.

As a scholar who studies Greek myth and has written a book about psychology and Homer’s epic poem, the “Odyssey,” I keep trying to understand what we have experienced in the U.S. during the COVID-19 era through my research.

Greek texts cannot name all their countless fallen heroes, but they show how to honor the lives of those lost to war or plague, and the significance of doing so.

Moral tales and the countless dead

Some of the earliest texts about deaths in plagues and war from ancient Greece emphasize the difference between the individuals who lead their citizens into disasters and the masses of people who suffer and die because of them.

Homer’s other epic, the “Iliad,” set in the conflict between the Greeks and the city of Troy, starts out by lamenting the “myriad Greeks sent to their doom” not by the war itself but the superhuman rage of Achilles, son of the goddess Thetis, and the most powerful of the Greek warriors. Achilles’ rage during the war against his commanding officer, Agamemnon, leads to the deaths of his own people.

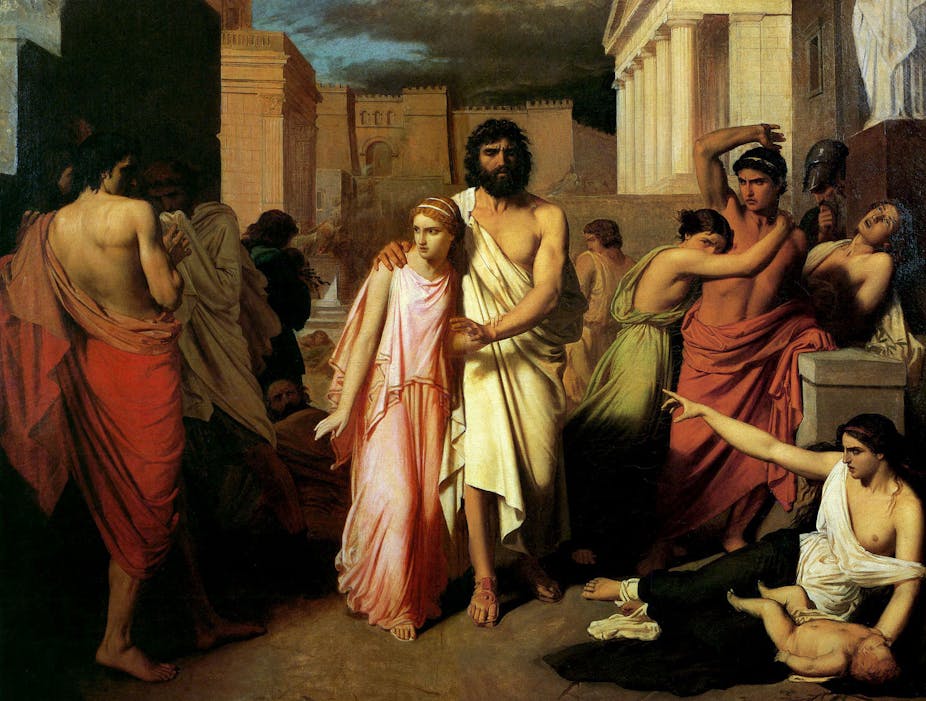

Nameless victims also haunt Sophocles’ Athenian tragedy, “Oedipus Tyrannus,” or “Oedipus the King,” when a plague afflicts the city of Thebes. An oracle says the plague will not end until the killer of Oedipus’ father Laius is brought to justice. Oedipus struggles to realize that he is the killer and cause of the plague, as the one who murdered his father and married his mother, not knowing who they are.

Probably the most famous account of a plague from ancient Greece comes from Thucydides’ “History of the Peloponnesian War,” a generation-long war between the city-states of Athens and Sparta from 432 to 404 B.C. Thucydides describes how a plague overtook Athens in 430 B.C.

Thucydides’ first-person account describes fevers and boils and frustrated doctors, but little sense of the individuals who suffered from it. Instead, he focuses on the breakdown of social order, how people abandoned their neighbors and loved ones, and how, shockingly, traditional burial rites were abandoned.

Modern estimates put the Athenian losses in this plague at 25% of the population, perhaps over 75,000 people.

Can we even conceive of the numbers?

Homer and Sophocles do not give names to individuals among the dead masses. As the narrator in the Iliad announces, someone would need “ten mouths and an inexhaustible voice” to name all those who fought at Troy. The contrast between the large numbers of undifferentiated dead and the heroes or leaders responsible for them helps the readers think about culpability. But this might also be a reflection of the limits of human cognition.

Our brains are not well suited to comprehending large numbers: We are good at comparing sums, but the larger a number gets, the harder it is for us to attach concrete meaning to it. This is in part why the milestone COVID-19 death tolls of 100,000 and 1,000,000 may mean as much to us as the “myriad deaths of Greeks” at the beginning of the “Iliad.”

Our ability to identify with and feel compassion for victims of violence decreases as the number lost increases, leaving us numb. We are also psychologically better suited at mourning our near and dear ones, or a handful of people, than a group. This is, lamentably, why mass killings and genocides are so difficult for many people to process emotionally.

Burial and rhetoric

Our inability to comprehend large numbers of the dead render them faceless and nameless. This can create a tension with practices for honoring those we have lost. Greek myth centers burial rites as the honor due to the dead. Their practices included caring for the body through cremation or burial, but also through lamentation and the creation of memory.

Indeed, the final two books of Homer’s “Iliad” are lessons in how to memorialize the dead. First, Achilles holds a funeral and games in honor of his friend Patroclus, and then the Trojans retrieve and mourn their fallen defender, Hektor.

The eulogies of modern funerals function in part to help create a shared memory of a lost loved one. COVID-19, however, has not only exhausted people’s capacity to grieve through sheer numbers, it has also disrupted memorial practices.

In ancient Athens, there was a practice of providing an annual funeral speech for those who had died in service to the city. The speech was a sacred occasion that provided honor to the dead as a group. These speeches connected their sacrifice to civic survival and the glory of the state, situating their deaths in a story that connected their survivors’ past with future endeavors.

One of the most famous examples of ancient rhetoric comes from this practice. Thucydides places the funeral speech of Pericles, the leader of Athens and architect of its war with Sparta, at the end of the first year of the conflict, right before the onset of the plague. Pericles rallies his people not to mourn their losses but to praise their sacrifice.

The politics of counting

Nations can choose to memorialize the dead through a monument or a holiday. Such memorialization arises from a public and political will. But the number of lives lost are subject to selection.

U.S. COVID-19 deaths, for example, may be undercounted by a third because of local and national decisions on record keeping and classification. The impact of these losses is impossible to estimate. Worldwide, COVID-19 has become a long-term disabling event for millions. In the United States alone, a quarter of a million children have lost a caregiver to the pandemic.

It is important to count the numbers and to tell their stories, because what countries officially count in part communicates who they think matters. Consider, for instance, that the the number of Iraqis and Afghans killed during America’s wars in those regions is not known. By contrast, the number of American servicemen killed is well known.

The contrast between what is countable and what is felt brings tension to the stories of the Iliad, Oedipus and Thucydides’ “History of the Peloponnesian War.” Poorly read, these narratives glorify their failed leaders, but careful consideration can help readers see how many were lost to preserve a handful of names.

Who our nations count today will go a long way in telling future generations the story of the COVID-19 era. And it will also help define those who lived through it.