CHOGM: As the leaders of Commonwealth nations prepare to meet in Perth this week, The Conversation is examining the role of the biennial Commonwealth Heads of Government (CHOGM) Meeting.

In our second piece, Keely Boom and Aleta Lederwasch from the University of Technology ask whether CHOGM’s smaller nation members’ concerns about climate change will be drowned out.

Climate change promises to be a hot topic at this year’s Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in Perth, Australia.

The biennial gathering brings together the heads of government of all 54 Commonwealth countries.

CHOGM 2011 will be the largest gathering of world leaders ever hosted by Australia. Prime Minister Julia Gillard will chair the event.

The meeting comes just weeks before the 17th Conference of the Parties (COP17) when world leaders will meet in Durban, South Africa, to negotiate global action on climate change as part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) process.

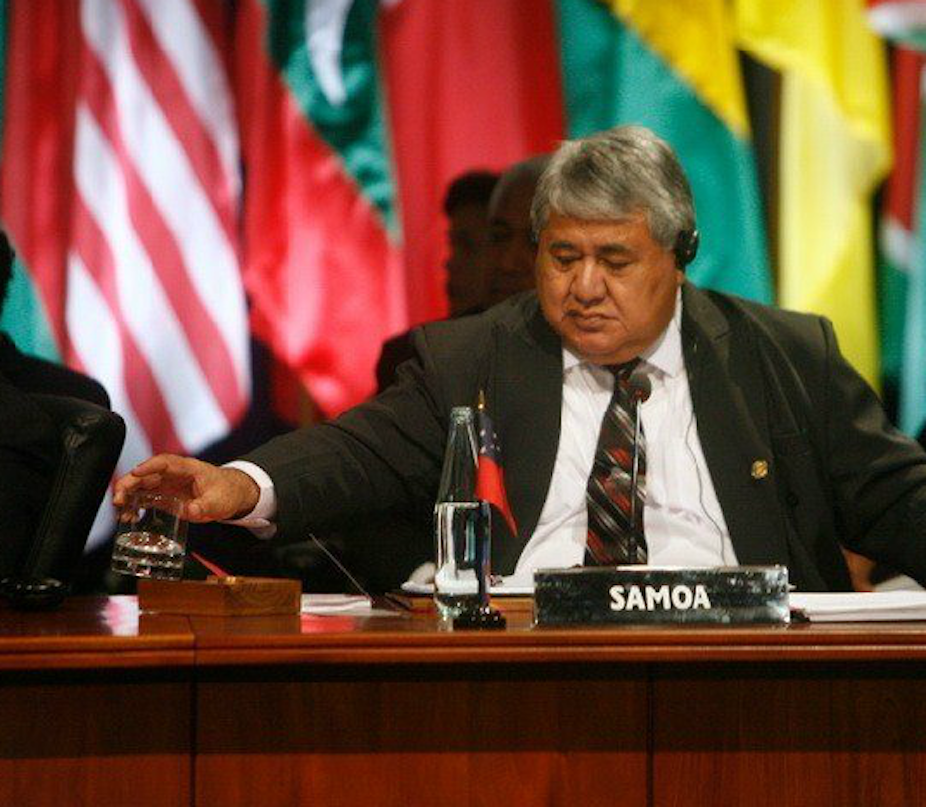

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in the Pacific including Tuvalu, Kiribati and Samoa are seeking urgent action on climate change, including binding emission targets and faster adaptation funding.

These countries are extremely vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including sea level rise and ocean acidication. More than 75 million Pacific Islanders may be displaced due to climate change by 2050.

Will Pacific voices be drowned out by the concerns of larger members at CHOGM?

Mitigation and CHOGM’s 2007 Action Plan

In 2007, CHOGM agreed to the Lake Victoria Commonwealth Climate Action Plan. The Action Plan is both a statement of political will and a program of work.

The program of work includes helping vulnerable member countries build their negotiating capacities, supporting research and debate, and developing skills (such as modelling climate change impacts).

The Action Plan recognised that climate change is a “direct threat to the very survival” of some member countries.

Australia and New Zealand: big brothers or big bullies?

Pacific Island countries actually tried to achieve binding mitigation targets at CHOGM 2007. Yet Australia ran a campaign against the proposal and was supported by Canada.

The Action Plan did not include any binding targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions – Australia had succeeded.

Instead the Action Plan called for a post-2012 UNFCCC deal that included a “long-term aspirational global goal for emissions reduction to which all countries would contribute”.

New Zealand even tried to prevent discussions about climate change at CHOGM 2009. New Zealand’s argument was that CHOGM should not be taken over by issues covered by the UNFCCC process.

Although CHOGM 2009 agreed to the Commonwealth Climate Change Declaration, the document failed to include any emissions targets or commitments.

Australia and New Zealand are sometimes described as the “big brothers” of SIDS in the Pacific. Yet this sort of activity may be more akin to school-yard bullying.

Adaptation funding: does the offer meet the call?

To adapt and strategically respond to the changing climate, the SIDS will need several tens of billions of dollars of financial support annually.

According to estimates made by the UNFCCC, World Bank and the European Union Commission, poor countries will need between $20 billion and $100 billion in support annually by 2020.

At the CHOGM 2009, Britain and France proposed an annual US$10 billion fast-track adaptation fund for developing nations. Australia said it would contribute a “fair share” to the fund.

Commitments were made at Copenhagen to launch the fund in 2010. Unfortunately, the commitments were non-binding.

Efforts were made at Cancun to get the fund on track by asking the “transition committee” to recommend a governing structure for the fund.

The draft recommendations report will be considered at Durban this year and voting rights over the fund are likely to cause debate.

While developing countries comprise a large majority of the fund’s general membership, developed countries dominate the Funds Board.

So have developing nations had enough financial support to date?

Quite simply: no.

A World Bank report estimates that money reaching developed countries for managing climate change damage and threats covers less than 5% of what is needed.

As the Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina, has stated: “the amounts are meagre in comparison to the needs”.

Why isn’t the Pacific being heard?

Although almost half of CHOGM are SIDS – many of which are in the Pacific their voices are often overruled at CHOGM.

As a consensus organisation, CHOGM requires all member countries to support any of its decisions.

This makes it very difficult for the Pacific Islands countries to achieve anything beyond non-binding statements of political will. This is particularly true when countries such as New Zealand and Australia undermine their efforts.

On the other hand, the fact that the new UNFCCC fund currently being developed came out of CHOGM 2009 suggests this year’s CHOGM could provide a opportunity.

Acting in the interests of the Commonwealth

All Commonwealth member states will feel the impacts of a changing climate on SIDS, from answering state of emergency calls such as the current water crisis in Tuvalu to dealing with longer-term challenges such as displacement.

An opportunity exists at CHOGM 2011 to demonstrate the Commonwealth’s capacity for compassionate and creative collaborations on both adaptation funding and mitigation.

Such collaboration would feed constructively into the UNFCCC meeting at Durban and would be in the interests of the “common wealth” of all member nations.

Read more:

Our complex relationship with India

Can CHOGM take the reins in the face of NCD disaster?

A long line of discrimination, but should the succession to the throne be changed?

Why the Commonwealth must take action against Sri Lankan war crimes