As late as 1976, in what must have been one of the last things he wrote, the poet and controversialist James McAuley asserted, in a foreword to a volume of cartoons by George Molnar entitled Moral Tales:

Satire is essentially a conservative art. Making fun of aberration from an eccentric point of view isn’t very rewarding. Good satire measures the angle of divergence of human thought from the norm – that is, from commonsense realism.

Why does this sound so wide of the mark as an account of modern Australian political cartoons? Why do we now tend to assume that cartoons and cartoonists are anything but conservative? It sounds like a world we have lost, if it ever existed at all.

The Australian newspaper is currently celebrating 50 years in print. Paradoxical as it now seems – and has seemed since a point in 1975 (October 15 by my reading) when the paper’s editorial line definitively turned – the early Australian provides a large part of the answer to these questions.

The 1950s were a quiet time for political cartooning in Australia. Smith’s Weekly had died of natural causes in 1950 and The Bulletin was long past its best, increasingly confined to a rural rump or readers and a reactionary politics.

Daily newspapers often lacked editorial cartoons entirely, making do with sporting caricatures and apolitical “funnies” for comic relief. Only George Molnar at the Sydney Morning Herald commanded a prominent place for visual satire, and his focus was often more on social than political critique.

Cartoons make a comeback

In the 1960s Australian political cartoons were transformed by three major events.

First was the arrival of cartoonist Les Tanner at the Bulletin in 1961, after editor Donald Horne was given the job of reviving or killing it by Frank Packer.

Horne took “Australia for the White Man” from the banner, injected life into the weekly, and employed Tanner, a communist though not a vocal one, to take the visual tradition away from the paths trod by Cold Warriors such as Norman Lindsay and Ted Scorfield.

The Bulletin was the home publication for the Australian black and white art tradition, and Tanner used his tenure as cartoon editor there to work a transformation both in style and content for cartoons.

To cut a long story short, the cartoons Tanner drew and sponsored were more visually and politically radical than the house style of the 1950s, especially in a departure from the caricatures and topoi of the laconic bush tradition.

Tanner was also integral to the third major event – when he left the Bulletin in 1967 to go to the Melbourne Age and usher in the visual and critical aspects of the great era of that paper under Graham Perkin and his successors. But the numerate among you will note that I have leapt from first to third.

It is the second part of this story that I will now focus on.

Bruce Petty at The Australian

One of the artists Tanner published a lot at the Bulletin in the early 1960s was Bruce Petty, whose nervous line and busy images stressed the extent to which cartoons are political commentary rather than illustration.

After travel to London where he worked on Punch, his first regular gig as a first political cartoonist at Rupert Murdoch’s Daily Mirror in Sydney in 1963. He then went to Canberra in 1964 for the start of The Australian:

We all went to Canberra like a big wagon train. We were there to enlighten the world. I was pretty much allowed to choose what to draw, but it would be the story of the day or yesterday’s story.

And in those years the stories were the most powerful that I have known. Australia joined the rest of the world. Asia was joining, but not on our terms. We each had to invent politics based on fairly random inputs and experience.

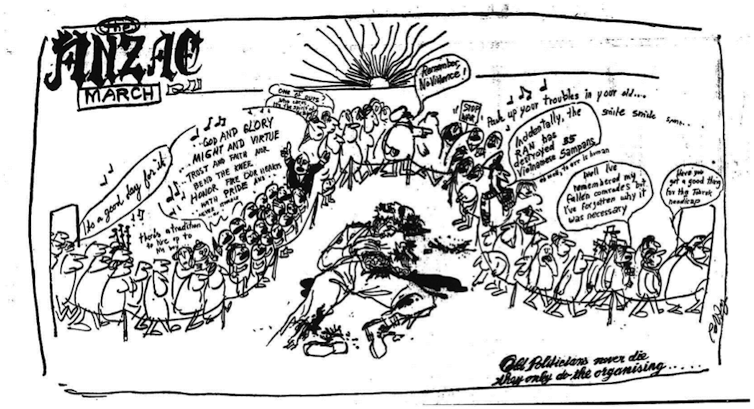

Petty’s cartooning was one of the material ways in which the early Australian shook up a fairly stagnant broadsheet market. Consider the cartoon below, published the day after Anzac Day 1969.

By then, the moratorium movement had substantially turned public opinion against the war. How would one bid up the anti-war pressure on the holiest day of Australian nationalism? Since Alan Seymour’s play The One Day of the Year, some resistance to Anzac Day jingoism had been growing.

This is an affront to social and artistic convention.

The scale of the dismembered corpse – as much of Long Tan as of Gallipoli, as much a Viet Cong as an Anzac – is shocking. A parade of chattering and hymn-singing spectators is detouring around an emblem of the horror of war worthy of Goya.

They are ignorant and almost brutally complacent. Their parade has nothing to do with the reality of war and everything to do with the deceptive schemes of politicians.

Would any newspaper print this cartoon today, let alone anywhere near Anzac Day?

The attack on Anzac for Petty and his colleagues was an attack on the old, insular, white Australia of the mid-20th century. The Australian was part of that socially progressive movement that wanted to disrupt the complacency of “the Lucky Country”.

It has always been a vanguard newspaper, wanting to shift the nation’s sense of itself, not merely to reflect it. Now its view of Anzac is part of a patriotic movement that mourns the passing of White Australia and supports the expansive view of US cultural and military power; yet the paper still campaigns for many sorts of economic and social reform.

The remystification of Anzac that is breaking over us in a tsunami of sentiment as the centenary arrives is a wide-spread phenomenon.

The Oz’s part in this is very different from its part in the anti-militarism of the Vietnam War, but it is part of a continued ambition not merely to express but to shape and influence public opinion.