It was a time of political uncertainty, cultural conflict and social change. Private ventures exploited technological advances and natural resources, generating unprecedented fortunes while wreaking havoc on local communities and environments. The working poor crowded cities, spurring property-holders to develop increased surveillance and incarceration regimes. Rural areas lay desolate, buildings vacant, churches empty — the stuff of moralistic elegies.

Epidemics raged, forcing quarantines in the ports and lockdowns in the streets. Mortality data was the stuff of weekly news and commentary.

Depending on the perspective, mobility — chosen or compelled — was either the cause or the consequence of general disorder. Uncontrolled mobility was associated with political instability, moral degeneracy and social breakdown. However, one form of planned mobility promised to solve these problems: colonization.

Europe and its former empires have changed a lot since the 17th century. But the persistence of colonialism as a supposed panacea suggests we are not as far from the early modern period as we think.

Colonial promise of limitless growth

Seventeenth-century colonial schemes involved plantations around the Atlantic, and motivations that now sound archaic. Advocates of expansion such as the English writer Richard Hakluyt, whose Discourse of Western Planting (1584) outlined the benefits of empire for Queen Elizabeth: the colonization of the New World would prevent Spanish Catholic hegemony and provide a chance to claim Indigenous souls for Protestantism.

But a key promise was the economic and social renewal of the mother country through new commodities, trades and territory. Above all, planned mobility would cure the ills of apparent overpopulation. Sending the poor overseas to cut timber, mine gold or farm cane would, according to Hakluyt, turn the “multitudes of loiterers and idle vagabonds” that “swarm(ed)” England’s streets and “pestered and stuffed” its prisons into industrious workers, providing raw materials and a reason to multiply. Colonization would fuel limitless growth.

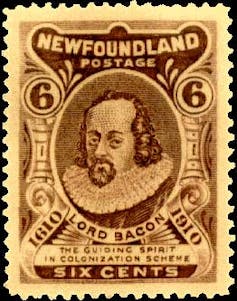

As English plantations took shape in Ulster, Virginia, New England and the Caribbean, “projectors” — individuals (nearly always men) who promised to use new kinds of knowledge to radically and profitably transform society — tied mobility to new sciences and technologies. They were inspired as much by English philosopher Francis Bacon’s vision of a tech-centred state in The New Atlantis as by his advocacy of observation and experiment.

Discovery and invention

The English agriculturalist Gabriel Plattes cautioned in 1639 that “the finding of new worlds is not like to be a perpetual trade.” But many more saw a supposedly vacant America as an invitation to transplant people, plants and machinery.

The inventor Cressy Dymock (from Lincolnshire, where fen-drainage schemes were turning wetlands dry) sought support for a “perpetual motion engine” that would plough fields in England, clear forest in Virginia and drive sugar mills in Barbados. Dymock identified private profit and the public good by speeding plantation and replacing costly draught animals with cheaper enslaved labour. Projects across the empire would employ the idle, create “elbow-room,” heal “unnatural divisions” and make England “the garden of the world.”

Extraterrestrial exploration

Today, the moon and Mars are in projectors’ sights. And the promises billionaires Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos make for colonization are similar in ambition to those of four centuries ago.

As Bezos told an audience at the International Space Development Conference in 2018: “We will have to leave this planet, and we’re going to leave it, and it’s going to make this planet better.”

Bezos traces his thinking to Princeton physicist Gerald O’Neill, whose 1974 article “The Colonization of Space” (and 1977 book, The High Frontier) presented orbiting settlements as solutions to nearly every major problem facing the Earth. Bezos echoes O’Neill’s proposal to move heavy industry — and industrial labour — off the planet, rezoning Earth as a mostly residential, green space. A garden, as it were.

Musk’s plans for Mars are at once more cynical and more grandiose, in timeline and technical requirements if not in ultimate extent. They center on the dubious possibility of “terraforming” Mars using resources and technologies that don’t yet exist.

Musk planned to send the first humans to Mars in 2024, and by 2030, he envisioned breaking ground on a city, launching as many as 100,000 voyages from Earth to Mars within a century.

As of 2020, the timeline had been pushed back slightly, in part because terraforming may require bombarding Mars with 10,000 nuclear missiles to start. But the vision – a Mars of thriving crops, pizza joints and “entrepreneurial opportunities,” preserving life and paying dividends while Earth becomes increasingly uninhabitable — remains. Like the colonial company-states of the 17th and 18th centuries, Musk’s SpaceX leans heavily on government backing but will make its own laws on its newly settled planet.

A failure of the imagination

The techno-utopian visions of Musk and Bezos betray some of the same assumptions as their early modern forebears. They offer colonialism as a panacea for complex social, political and economic ills, rather than attempting to work towards a better world within the constraints of our environment.

And rather than facing the palpably devastating consequences of an ideology of limitless growth on our planet, they seek to export it, unaltered, into space. They imagine themselves capable of creating liveable environments where none exist.

But for all their futuristic imagery, they have failed to imagine a different world. And they have ignored the history of colonialism on this one. Empire never recreated Eden, but it did fuel centuries of growth based on expropriation, enslavement and environmental transformation in defiance of all limits. We are struggling with these consequences today.