The centenary of the birth of Charmian Clift takes place on August 30. It comes at a time when the renowned Australian writer is, as they say, having a moment.

Clift’s typewriter has been still for over half a century, but the fascination with her life and writing shows little signs of abating. Recent years have seen new Australian editions of her work in its various genres: fiction, memoir and journalistic essays. There has been a play about her in the theatres. A documentary is in the making and a feature film is in pre-production.

Next year we will see “new” writing from Clift, with the first publication of The End of the Morning, the autobiographical novel she was working on at the time of her death.

Interest in Clift’s legacy has also been evident overseas, where her two memoirs of Greek island living – Mermaid Singing (1956) and Peel Me a Lotus (1959) – have been republished in the UK after more than six decades, to often rapturous reviews. These books have appeared in translation for the first time in Greek, Spanish and Catalan – a measure of an international readership that was elusive during Clift’s lifetime.

And if this cake needed further icing, it comes in the form of Clift and her writer husband George Johnston emerging as “characters” in international novels and films. They have come to exemplify the experience of artistic expatriation, solidarity and dissolution that transpired on the island of Hydra in the 1950s and 1960s.

Read more: Friday essay: a fresh perspective on Leonard Cohen and the island that inspired him

A riveting portrait

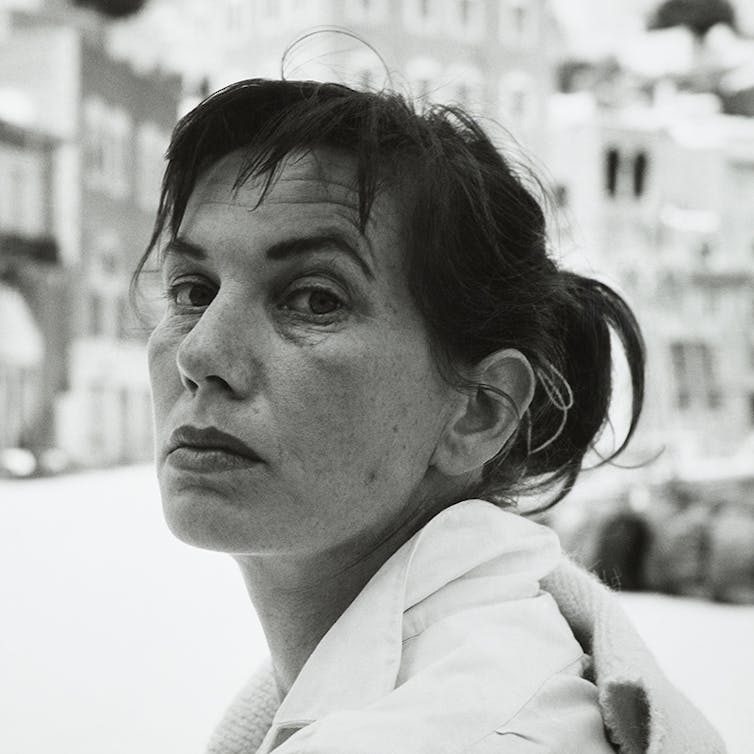

Exactly why Clift enjoys this prolonged afterlife when once far-better-known mid-century writers struggle to sustain reputations is a matter for another time. But there is a hint to be found in a fragment of her extraordinary life – a photographic moment that condenses her charismatic and enigmatic essence into a single, riveting image. It is a photograph that is remarkable in itself, but made extraordinary by the use to which it would be put.

Intrinsic to the photo’s quality is its creator. It was the work of Liselotte Strelow (1909-1981), a significant German portrait photographer. Her powerful and intensely focused black-and-white images identified her as an Autorenphotographie – an artist-photographer – capable of extracting from the human face a deep reflection of character and interiority.

Strelow built her stellar reputation with memorable portraits of the artistic, intellectual and political greats of postwar Europe, including Jean Cocteau, Salvador Dali, Marlene Dietrich, Henry Moore, Thomas Mann and Maria Callas. Her portrait of Clift is as well realised as anything in her body of work.

Also critical to the photo’s success is that Strelow found in Clift a subject who was prepared to match her ambition. Clift exposed herself in a starkly unadorned and unguarded manner. Her hair is thrown about and seemingly tied with string; her skin flaws are clearly visible. She has what appears to be a bruised left eye.

Devoid of coquetry or coyness, Clift’s direct gaze penetrates the camera lens with uncommon intensity. She appears both assertive and vulnerable.

Clift wasn’t new to working with photographers. She first attracted attention by winning a beach-girl photo competition in 1941 with a image taken by her sister, Margaret. She then undertook part-time photographic modelling in wartime Sydney. As her biographer Nadia Wheatley noted, Clift was blessed with “that indefinable thing which makes a certain face photogenic. It is clear that the camera loved Charmian – and that the feeling was mutual.”

This much is true, but what is on show in Strelow’s image is something more than a straightforward representation of a photogenic subject. Working in tandem, Strelow and Clift have created an image that reaches beyond the superficial appeal of an attractively structured face to reveal a scintillating intellect, and expose layers of anguish and self-doubt. The result is a masterwork of “Australian” photographic portraiture.

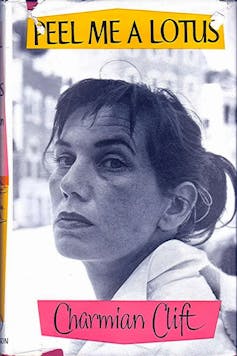

Little is known of the context in which the photo was taken, or even when Strelow travelled to Hydra, which is demonstrably where it was taken. It is almost certain, however, that the image was specifically required (by author and publisher) for use with Clift’s forthcoming book, Peel Me a Lotus, a highly personal account of her Hydra life.

Existential yin and yang

In some ways, the dust jacket designed for the first British edition of Peel Me a Lotus is entirely of its time. The stylised chevrons are highlighted by “of-the-moment” saturated colours and fonts that are typical of postwar design. What is unexpected is the use of an author photograph to adorn a travel memoir in the 1950s.

The 1950s continued the pre-war preference of British publishers for illustrated or graphically designed dust jackets, usually based on watercolours, woodcuts or pencil drawings, and adapted for two or three-colour offset printing. Clift’s previous travel memoir, Mermaid Singing, was typical. Both the front and back covers featured drawings by her friend, Australian artist Cedric Flower.

Author photos, if used, were relegated to the back cover or the internal cover flaps. It was extremely rare to find an author pictured on the front of a dust jacket, and particularly with a photo presenting the author as anything other than a confident and reassuring presence.

There were few precedents for a dust jacket portrait that challenged the reader in the manner of Strelow’s photo of Clift, which is far more likely to unsettle or provoke potential readers rather than offer reassurance. But somebody – very likely Clift herself – selected this image and promoted its use on the front cover.

And it was done with good reason, in that Clift’s achievement in Peel Me a Lotus is the literary equivalent of Strelow’s photo. The book’s success – and a key to its lasting appeal – is found in Clift’s willingness to go beyond the benign expectations of Mediterranean exoticism and take the reader into a darker personal experience of expatriation.

Peel Me a Lotus is made memorable because of its evocation of Clift’s existential yin and yang of exhilaration and despair, belonging and deracination. The book commences amid a blossom of optimism that accompanies the birth of a child, the buying of a house, and the embrace of the sun-drenched Hydra lifestyle. But it soon pitches headlong into the anxieties brought on by Clift’s recognition that she and Johnston are “marooned” in poverty.

The growing numbers of expats and tourists attracted to the island provide an irresistible link to the outside world and relief from growing tedium, while posing a threat to the personal dreams the couple were seeking to fulfil.

Clift describes how work and family suffer amid the dockside sociability. She and Johnston would “go home a little drunker than we ought to be, feeling vaguely worsted, jangling with some unspecified resentment, indefinably tainted”.

Her growing anguish in response to her increasingly complex reality is momentarily frozen by Strelow’s camera. The image exposes Clift’s realisation that the very circumstances that fed her creativity were also capable of depleting it. This compatibility between image and text transforms a great photo into the basis for one of the most compelling dust jackets produced for an Australian writer.

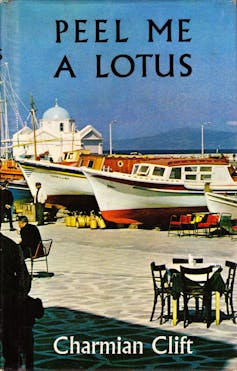

Peel Me a Lotus did not have its first Australian publication until a decade later, when it was occasioned by Clift’s suicide. For this edition, the dust jacket consisted of a stock photo of cliched “Greekness” used as a stand-in for Hydra. Specifically, the photo depicted the blue-domed dockside church of Agios Nikolaos on Mykonos.

It was the first of a series of Australian editions to feature covers of generic domed churches unaffiliated with Hydra – an island with its own remarkable architecture, but notably devoid of these classic painted domes. One can confidently assume that Clift would have been appalled to see such photos deceptively embellishing a book that was emphatically about the beloved and very singular island that shaped her expatriation for a decade.

It is easy to understand the marketing appeal of these images, which speak, however inaccurately, to an audience of sun-seeking holiday makers dreaming of a Greek island summer. They are, however, an inadequate representation not only of Hydra, but Clift’s intentions in marshalling her writerly genius to expose the fractures in her own psyche.

It is a pity that Australian readers of Peel Me a Lotus were denied the opportunity to look into the eyes and soul of the woman who was both living the dream and confronting its consequences.