In the run up to the World Cup, the scene depicted in Brazil by the international press was split between two simple narratives. On one hand: disaster, with protests against the tournament gaining much publicity. On the other: football lovers, semi-naked women on beaches and corrupt millionaire elites versus shanty town dwellers. This is despite Brazil’s three decades of a gradual democratisation and rise to the position of the world’s seventh wealthiest economy. Suffice to say, this has contributed to a more complex situation.

The Brazilian press also provided their share of “colonial” images of European foreigners dazzled by a tropical country and a friendly people: the German footballer Miroslav Klose for instance appeared dancing alongside 20 members of the indigenous tribe Pataxo de Coroa Vermelha, in the southern state of Bahia. Meanwhile, there was also an obsession with providing images of buses on fire and angry poor people screaming in foreign press.

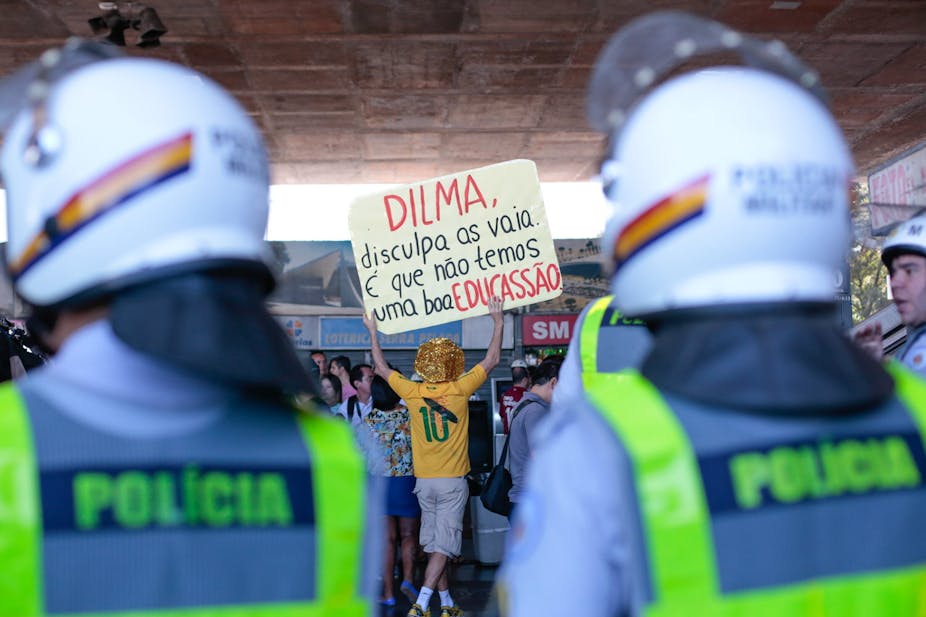

The negative coverage reflected to some extent the mood of disillusionment and anger of Brazilians at excessive government spending. The tournament cost US$11.3 billion to stage, dwarfing the amount invested in public transport, hospitals and schools in a country where citizens pay high taxes and money is badly spent by the state. But the black and white narratives are slowly making room for more sophisticated analyses of Brazilian society.

Democratisation and media expansion

Many Brazilians are trying to break free from both oppressive global structures (for example FIFA who are estimated to to make a profit of US$2.6 billion from the tournament) and local powers, among others the state police authorities who crack down on protesters. The growth of the internet as a political blogosphere and social media has facilitated their protests and a wider understanding of the roots of Brazil’s structural inequalities.

This started before the notorious June 2013 demonstrations and has very much been a consequence of both political democratisation and an ongoing diversification of the media since the 1990s. This has included online media, with sites from different under-represented groups, many of whom are slowly gaining a voice and debating various issues in the blogosphere, from balance in journalism, to public services and political reform of the party system.

Many citizens have taken advantage of the world stage to express anxiety for a better future with a “FIFA standard” of public services. This includes not just more political participation, but also demands for a more democratic and better quality media. Thus the world has seen the tube strikers in Sao Paulo and various other smaller but not less significant protests.

In the run up to the presidential elections in October 2014, where the re-election of Dilma Rousseff is cast in a shadow of doubt, the question that seems to be on everybody’s lips is less who will win the World Cup, but rather where will we go from here?

More nuanced views

In the last year, Brazil’s media coverage has shifted from condemning demonstrators on the basis of a law and order framework, to providing more balanced coverage that underlines the legitimacy of their demands. In doing so, the media is better serving its citizens. The success of online citizen journalism coverage and alternative media outlets such as Midia Ninja has played a large role in pressuring the mainstream to take this more balanced view.

Abroad, too, newspapers have correctly explored some of the roots of all the anxiety. Even tabloids like the Daily Star have pointed out the mix of security measures (57,000 military personnel were deployed), FIFA corruption and the lack of enthusiasm of many Brazilians, including the displacement of 200,000 from their homes due to construction work. Another highlight from The Guardian was the story on the reasons to root for the protesters. Thus a key legacy of the protests seems to have been their capacity to contribute to changes in perception, and a more (positive) sympathetic understanding of a whole people.

In spite of the progress it has made, the mainstream Brazilian media remains highly politicised and concentrated. It is represented by organisations such as Globo and Folha de Sao Paulo, which have shown some signs of improvement in terms of professionalism in the last decades.

Critics argue that they have been using the protests and the World Cup for political gain, being quick to point out the delays in airports and stadiums whilst ignoring FIFA’s impositions as well as their own profit with the event. Globo TV for instance has a monopoly over the transmission of events and it was at the centre of the July 2013 protests, which among others also saw protesters demand media democratisation alongside quality public services. They have also accused other media of trying to undermine President Rousseff’s government, and gain support for the opposition in the coming October elections.

Mixed blessings

The World Cup in all of this is proving to be a mixed blessing. On the one hand it has exposed the fragility of Brazil’s democracy, its levels of corruption and the lack of preparation before the World Cup, affecting its image and claims to “superpower” status. On a more positive note, it is contributing to changing perceptions, underlining the growing political and social consciousness of its people. After all, this is a country that has seen rapid advancements in recent years: a middle class now composed of 108 million people, with extreme levels of poverty falling down to 6% of the population.

Other changes include the approval of the internet draft bill, which safeguards net neutrality and freedom of expression – and which is being seen as a model for other countries. There have also been further discussions on media reform, anticipated to occur in the coming year.

Changes have been slow, making it evident that it is more deep-rooted problems that are a cause for concern. These include political corruption, police repression, concentrated mainstream media and a lack of a serious commitment to quality public services like education and healthcare, not to mention a better debate in the public sphere on these crucial needs.

These are the real tools for long-term development, and not just the minerals and other products that are currently being devoured by China. Only time will tell what the legacy of the World Cup will be. But what is emerging is a new Brazil, a more complex and fascinating one that is not passive and is pushing forward for more change and equality.