This year’s cultural debates about the constitution of the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards judging panels are now giving way to consideration of the shortlists and their relative worth.

Even as these debates wane, I have to declare, factually, that no contemporary academics in literature and history are represented among the judges.

To make this point clearly, have a look at the make-up of the Man Booker prize judging panel for 2014. On the panel, chaired by philosopher A.C. Grayling there is a depth of current literary critical academic expertise which should make the Australian panel-makers blush deeply.

What are the panel-makers scared of?

In Australia, this almost total lack of academic expertise is true of the Prime Minister’s Awards panel and the Miles Franklin Award. Last year’s Miles judging panel was made up of journalists, arts administrators, booksellers and one Emeritus Professor.

Of course there is expertise in that line-up, but hey, where, oh where, is the expertise of our top academic thinkers in literary studies and history? What are the panel-makers scared of?

It’s true that the phenomenon of these Australian awards – media and market-hyped as they are – are not the central interest of scholarly researchers. But the fact academic professional expertise is almost completely sidelined in Australia must be an indication of something – ignorance of who our scholars are – on the part of those who constitute such panels?

Fear that academic assessments (for “academic” read “informed, careful, large-view, contextual modes of reading”) might make public pundits look silly? Is it embarrassment about the depth of reading and debate academics generate?

These are fighting words, of course, and they’re coming from an academic. But the larger cultural point still stands: there is a deeply impoverishing divide between academic knowledge and media/ market-driven instrumentalist interests in literature.

After the dust settles, and the winners receive their moment of fame, and a deserved pay-cheque, academics who write national and international research papers and books about literature and history, who set curricula and teach students with different abilities, from multiple class, age and ethnic sectors, continue their task of selecting and teaching texts they see to be speaking into already dynamic, international debates.

Surely this expertise is being wasted in Australia, when it comes to the public valuing of literature.

The fiction shortlist

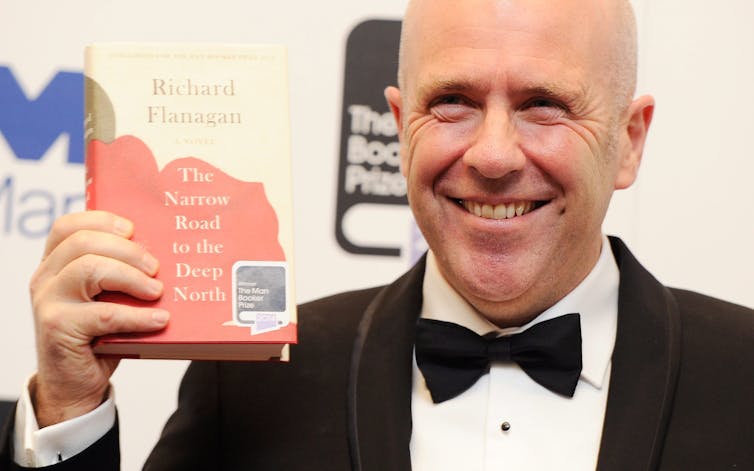

So what do the shortlists for the PM’s Awards look like? The fiction list contains the already prize-winning novelists Richard Flanagan, Fiona McFarlane, Alex Miller and Steven Carroll, plus a collection of essays by Nicholas Rothwell, described in the Guardian review by Alex Clarke in this way:

This sort of global psychogeography encourages a certain grandiose mysticism; filled with coincidences and convergences, symbols and auguries, its attempts to reach what is out of sight or already disappeared make it by definition unsuccessful, unable to achieve anything beyond a kind of yearning provisionality. To some extent, susceptibility to this way of seeing the world is a matter of personal taste. But the attempts to forge connections also make for a magpie brilliance …

As is often true of newspaper reviews, there’s a bit both ways in this one. Ouch to “grandiose mysticism”; and outrider pride, or another grimace, for “magpie brilliance”, depending on what you want, I suppose.

The works by the four novelists are sustained, imaginative, daring and enthralling, each one. Both Flanagan and Carroll revisit and reimagine the second world war, the first in Burma and POW camps along the death railway, the second in the London blitz. I am persuaded by Susan Lever’s balanced, informed review of The Narrow Road to the Deep North when she concludes that:

This novel, then, does not make its suffering characters virtuous, but it does uphold a more social and communal notion of virtue. Ultimately, it is a work of filial and national piety …

I would add, though, that there is a more pervasive sense of forgetting, meaninglessness and ontological scepticism permeating this novel, perhaps despite its humanist themes and seeming intent. Yes, there are the low-key heroes who stand up for conscience and justice, as much as they can among the horrors of the POW camps. But Flanagan does work hard to convince us that many Japanese too had a strong “social and communal notion of virtue”.

Such virtue is not just “ours”. There is a sense of alienation and human impotence that also seeps through the novel’s exposure of literature and its failure to make any difference. Or rather, literature is seen to bolster individual equanimity, but also relentless violence, equally.

Humans, in this novel, are just and corrupt, humble and narcissistic, lovers of beauty and violence, selfish and selfless. In a strange way, the novel writes of human intimacy and love, but finally casts a net of estrangement, forgetting and pointlessness across history and relationships. It’s indicative that the novel’s most riveting scenes are those of violence and the continual reduction of human bodies to maggot-infested corpses.

There is no space here to discuss all the novels on the fiction list, but commanding and substantive reviews of Carroll’s A World of Other People, McFarlane’s The Night Guest and Miller’s Coal Creek make clear arguments.

Eyrie by Tim Winton, The Swan Book by Alexis Wright, and All the Birds, Singing by Evie Wyld, all shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Award (with Wyld the winner), are not shortlisted by this judging panel. The Narrow Road and The Night Guest are on both shortlists.

The non-fiction shortlist

In the non-fiction list, war is again a theme in Rendezvous with Destiny by Michael Fullilove. Despite the clichéd (or is that “media savvy”) title and cover of this volume, readers may be interested in what the New York Times described as “an entertaining, if truncated history”.

The reviewer, David Nasaw wrote:

Regrettably, in this, as in other histories written as collective biographies, the whole ends up being less than the sum of its parts.

In a wonderfully coruscating, sardonic and hardly objective Monthly review of The Lucky Culture by Nick Cater, Mark Latham argues that most of Cater’s arguments “… are imported from neo-con journals in the US and applied crudely to Australian circumstances”.

Latham writes:

I had great expectations for the intellectual firepower mustered in The Lucky Culture. In the book’s acknowledgements, it is clear Cater has collaborated closely with the best and brightest of Australian conservatism, most notably his News Ltd colleagues Paul Kelly, Christopher Pearson, Henry Ergas and Rebecca Weisser, plus fellow travellers Peter Coleman and Gerard Henderson. This was to be their magnum opus.

But the results are feeble.

Gerard Henderson, Peter Coleman, Nick Cater … the links in another would-be ruling class? Does Cater’s work amount to any more than another attack on Australian intellectuals? Readers will decide, despite (or perhaps because of) the PM’s Award winners.

The three other shortlisted works are biographies: Phillip Dwyer’s Citizen Emperor being the second volume of the biography of Napoleon; Helen Trinca’s Madeleine: A Life of Madeleine St John, the tightly written life-story of a little known Australian novelist; and Gabrielle Carey’s Moving Among Strangers, an intimate memoir of expatriate Australian novelist Randolph Stow and his connections with Carey’s family.

Bernadette Brennan has written a marvellous, comprehensive and positive review of Carey’s work, concluding:

By a literary homecoming I mean that Moving Among Strangers, while traversing new territory, also returns to the pain and loss articulated in [Carey’s earlier works] In My Father’s House, So Many Selves and Waiting Room. At the conclusion of this new work, however, there is a notable sense of peace, healing and love.

So, who will win the Prime Minister’s Awards for 2014? And more importantly, how is the community of readers, teachers, students, booksellers, librarians and other involved members to be more productively constructed?