The sudden announcement by the Canadian Women’s Hockey League (CWHL) that it was ceasing operations has generated controversy and confusion. But as an academic who researches sport organizations, I have a different take — the CWHL closure opens the door for new and innovative women’s professional hockey opportunities.

On the surface, this ordeal reads as a tale of two leagues – one non-profit, the CWHL, and one for-profit, the National Women’s Hockey League (NWHL).

When the CWHL announced it was shutting down, the league’s board of directors stated “the business model has proven to be economically unsustainable.” Many fans and media took this to mean the non-profit model won’t work and the only option is the NWHL’s for-profit approach.

But this is a shortsighted view.

Closure is a catalyst for change

The closure of the CWHL is a catalyst for other key stakeholders to enter the scene — which has happened many times in the past for men’s professional hockey, where leagues have come and gone.

As my early doctoral research shows, many different stakeholders — including players, hockey federations, government and industry officials — have influenced the development of hockey over time.

The Canadian Amateur Hockey Association, created in 1914, initially resisted popular pressure to allow pay-to-play leagues to emerge. But as players opted for independent leagues that paid them, the CAHA loosened its regulations and accommodated a degree of professionalism while at the same time overseeing the development of hockey in the country.

This shift opened the market to hockey boosters and entrepreneurs, some of whom owned rinks and needed to have an attractive product in order to entice customers.

Money-making activity was fast and furious. Leagues came (the National Hockey League started in 1917) and went (the professional National Hockey Association lasted from 1909-18).

Rivalry between leagues

In his account of the emergence of the NHL, academic John Wong says separate camps jockeyed for position and profit as commercial hockey gained public interest. This is no different than the interplay — or as some note, the business rivalry — between the CWHL and NWHL that has unfolded since 2015, when the U.S.-based NWHL formed.

Women’s hockey also attracted economic interests during the early part of the 20th century. In his review of American women’s hockey in the First World War era, Andrew Holman notes that sports entrepreneurs sought new ways to sell the game, and as a result, women’s hockey was positioned as a commercial venture. The key point Holman makes about this historic time, though, is the rise and fall of the women’s game, including its professional form. It is important to note the CWHL story has happened before.

In his examination of hockey capital and the sports industry, historian Andrew Ross notes the complex men’s professional hockey landscape has included single-ownership leagues. He points out the NHL was once an unincorporated, non-profit organization.

Not a new model

The key lesson, then, is to recognize the CWHL model was not new and that this approach, as well as others, has existed and failed in the past. More importantly, these models, and the individuals that spearheaded them, pave the way for new and viable professional women’s hockey approaches to emerge.

Which brings us to the next phase of the story.

In my work on the global development of women’s hockey, I note there is no one “best” model, and that each country must develop at its own pace through a method that best suits its unique hockey system. The same is true for a professional women’s hockey league.

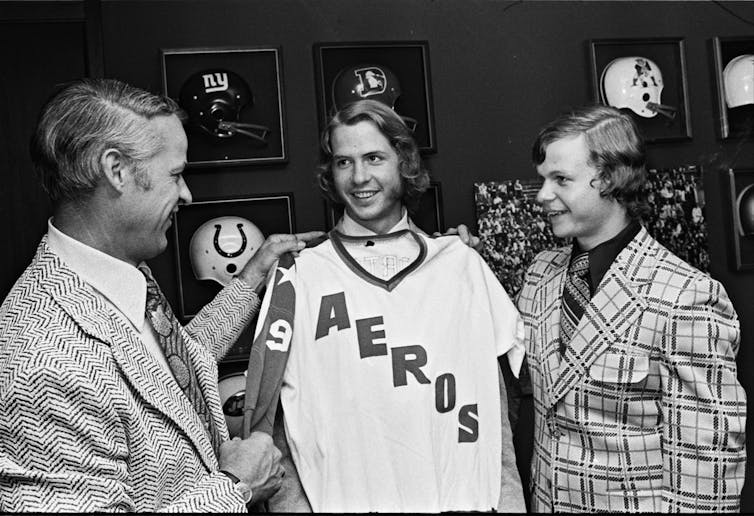

However, the CWHL’s shutdown created a vacuum. Just over 48 hours after the CWHL released news of its decision to close, the NWHL’s board announced an investment plan to establish two teams in Canada, and that it received a financial sponsor commitment from the NHL. And so, in a similar fashion to how the NHL and World Hockey Association, a rival men’s professional hockey league that existed from 1972-79, merged, one league shuts down while the others acquires some of its franchises and moves on as the lone commercial player in the female game.

Looking back to 2015 when the NWHL was formed, it’s interesting to reflect upon the CWHL’s response. The CWHL commissioner at the time, Brenda Andress, commented that the NWHL model was wrong and “that for us, it’s about sound operational and financial foundations first because we want to ensure the viability of the long term.”

During its 12 years of operation, the CWHL took this approach and in so doing, shaped the professional women’s hockey landscape. It’s now time for the next stage.