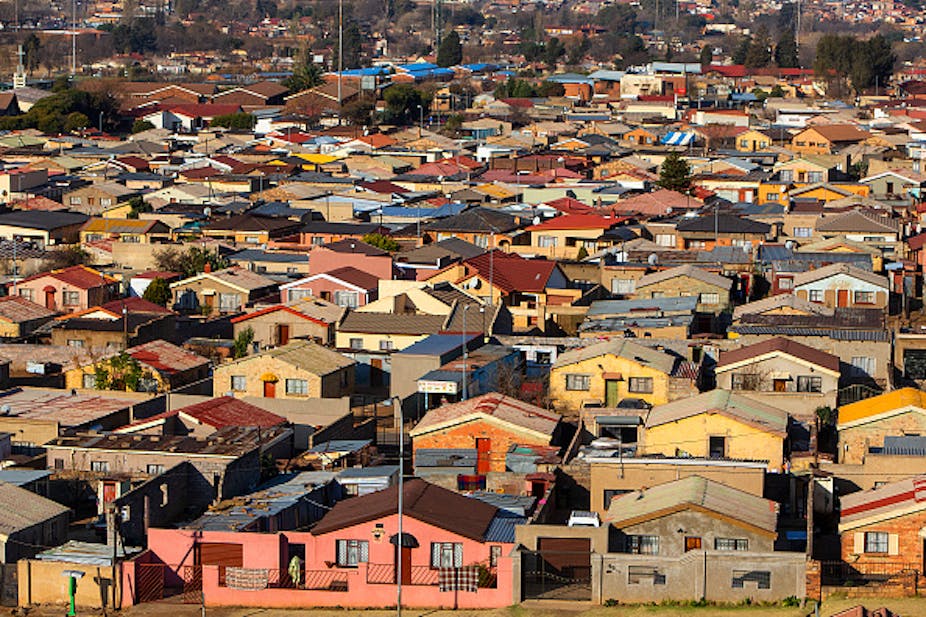

During apartheid, black South Africans could not own land – and therefore their homes – in what were classified as “white” cities. In racially segregated townships, living in “family houses” and passing them on depended officially on a range of permits. These were usually to rent from state authorities, but in some cases confusingly to build or buy a house without owning the plot underneath it, which was owned by the state.

A crucial measure in undoing apartheid was transferring ownership of township houses to their long-term residents. In 1986, a few years before apartheid’s end, the law changed to enable outright ownership for black people in urban areas. Subsequently, processes for transfer on a large scale were established.

This massive redistribution of public housing stock, alongside legal change, involved hundreds of thousands of homes. Township houses were now assets. The promise was improved security, rights, and inclusion in the property market.

But change did not necessarily give families greater security. Some family members benefited while others were left vulnerable. That is because the transfers – and the legal definitions of property and inheritance – do not account for how many people understand their homes: collective and cross-generational, available to an extended lineage.

This has led to confusion and heartache for hundreds of thousands of people. That confusion, I showed in a paper in 2021, extended to encounters with state administration, which can become the stage on which family disputes are played out.

As I argued in another paper, with Tshenolo Masha, these understandings of home and kinship warrant legal recognition – indeed, constitutional recognition – as urban custom. Various state officials have taken seriously the collective ownership of family houses, as a matter of customary norms and practice, through administration and court judgments. But they face the rigid limits of existing law.

The family house is central but effectively legally invisible, leaving many people uncertain about what it even means to own or inherit.

Collective home but individual property

For many residents, family houses belong collectively to multi-generational lineages. Often, a group of siblings is at the core – the children of an earlier, typically male, household head. Family members might build extra structures on the site to live in. Or they might come and go, but the home is a place to return to. The family house is defended as customary, drawing parallels with the rural homestead.

By the end of apartheid in 1994, regulation was patchy at best, but the occupancy permits were understood to affirm group entitlement because they listed family members, not just the householder.

In statutory law, at stake is an asset with one or more named owners – an indivisible plot or “erf” of land that includes its built structures. Owners can sell, or they can evict; other occupants have no legal right to stop them. When family houses were transferred, one person was generally registered as owner.

In some cases, the allocation to the registered householder was automatic. In others, there were hearings, but even here residents found their ideas of home and ownership marginalised. A family member would come forward as family “representative” and “custodian” of the collective home. But that representative would typically become the sole titleholder.

In many cases, relatives were unaware that this had happened, or even that an application for title had been made.

Inheritance: an added layer of complexity

Inheritance has added another layer to the problem.

Under apartheid there were separate inheritance rules for black people without wills. These were finally struck down by the Constitutional Court in 2000 and 2004. Magistrates’ courts were replaced by the dedicated inheritance office, the Master of the High Court. Inheritance by the eldest son was replaced by rules for all South Africans, prioritising spouses and children in nuclear families.

Once again, essential redress had the effect of narrowing which relationships would be recognised. When a custodian died, wider family members first discovered that they were not collective owners; then they realised they would not even inherit.

The family house is not a static idea in fights over the home. Warring parties may draw on both customary and legal concepts, sometimes at the same time. Among families that approach the state – and many do not – some subsequently drop out of official process.

There is no simple consensus about who gets what or about how this should be decided.

Efforts to resolve the issue

The family house is contested, yet it is key to arguments about what is fair – based not just on who owns, but on the nature of ownership.

State officials have repeatedly tried to make the system more responsive. In Gauteng province, where Johannesburg is located, housing tribunals were set up in the late 1990s to decide ownership and to broker family house rights agreements. They were intended to prevent custodians from selling houses or evicting relatives. But it turned out that they held no legal water: from the point of view of deeds registration, custodians’ ownership was unrestricted.

In the Master’s Office, where inheritance is administered, kin complain that their family home somehow became the property of one relative. In Johannesburg, officials try to explain the law, while where appropriate querying how title came to be acquired.

What they cannot do, though, is change the rules.

The courts, too, have highlighted problems with rigid law and procedure. In a 2004 Constitutional Court decision on inheritance, a dissenting judge warned that customary understandings of home and custodianship risked being sidelined by standardisation.

More recently in 2018, automatically upgrading householders to owners was declared unconstitutional. Men were usually documented as householders under apartheid, and gender discrimination was extended by giving them exclusive property rights.

Other judgments recognise the spirit of collective belonging and access, and they stop individuals from taking the house out of the families’ hands by inheritance or sale. But they cannot make legislation, so they send the question of who owns the house back to a tribunal.

Once again, solutions are restricted to workarounds.

Towards legal recognition

In 2022, the Shomang judgment in the North Gauteng High Court called for legally recognising the family house.

A sufficiently flexible notion of family title would be challenging to work out, and doubtless the basis for countless disputes. Surviving spouses need as much protection as the siblings in a lineage. But it would enable administrators and judges to mediate disputes in terms recognisable to the families involved. And to offer more than ad hoc workarounds.