Current discussions on the history of prohibition and drug laws in Canada have explored the narrative that Canada’s drug laws were fuelled by racism.

The story goes like this: A 1907 anti-immigration attack on Chinese establishments in Vancouver’s Chinatown brought the deputy minister of labour, William Lyon Mackenzie King, to the city to allocate reparations to businesses damaged in the riots. Some of the submissions came from opium “factories,” small businesses in which raw opium was refined for smoking.

King investigated the issue further, the story goes. In his initial report to Parliament, King noted that opium’s “baneful influences are too well-known to require comment”

and urged a law to ban opium for non-medicinal use. In July 1908, King’s boss, Rodolphe Lemieux, presented a one-page Opium Act to Parliament. It passed through the House of Commons with no notable commentary and through Senate with little more than a minor amendment.

Scholars have interpreted King’s initiative as anti-Chinese. The speed at which the Opium Act sailed through Parliament is also seen as evidence of a racist reaction to what may have been conceived to be a predominantly Chinese activity. As well, since restrictions on Chinese immigration to Canada were increasing, this is considered by many scholars to be a further attempt to restrict Chinese immigration.

Read more: How pot-smoking became illegal in Canada

But this narrative of our drug laws doesn’t tell the whole story: Further historical investigation reveals it to be even more complex and nuanced.

Understanding the history of our drug laws requires considering events well before 1908.

Opium restrictions began years earlier

Soon after Confederation, provincial governments began restricting access to specific medicines, including opium. Pharmacists and doctors argued that these medicines were poisons and could lead to death. The resulting pharmacy laws included “poisons schedules” of medicines that could be obtained only from a pharmacist or physician.

Opium was an important medicine at the time. It treated common illness symptoms, including coughs, pain and diarrhea. People who were prescribed opiates often developed a habit, much as they do today.

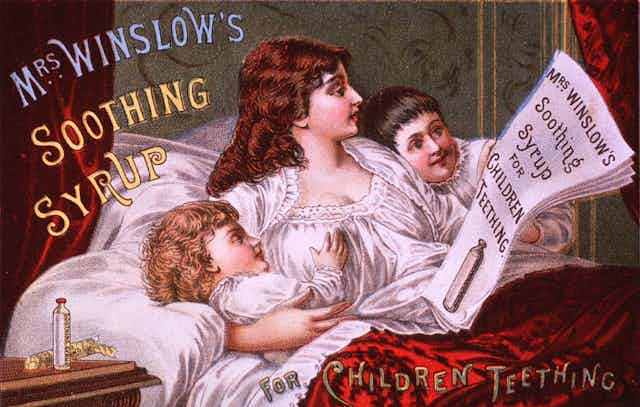

Restricted access meant they might turn to the patent medicine marketplace, buying painkillers, cough syrups and other products such as the popular Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, containing morphine and later nicknamed the “baby killer,” from grocers and general merchants. Those not addicted through prescription could easily develop a habit via these over-the-counter products.

By the late 1800s, cocaine, a topical anaesthetic, tonic and treatment for sneezing and runny noses, became a popular non-medical stimulant and appeared in many patent medicines. Not surprisingly, such self-prescribing caused doctors concern.

Canada’s provincial and federal governments began wrestling with the best way to deal with these products. Banning them was contrary to the laissez-faire economic rationale of the time. The result was a series of attempts to restrict access to patent medicines at the provincial level, and to mandate labelling and inspection of them at the federal level.

Debates about opium and cocaine

Legislation to regulate patent medicines was debated in Ottawa in 1906, 1907 and 1908. In these debates, the problems of opium were well-aired.

In June 1908, the Proprietary or Patent Medicine Act (PPMA) passed third reading. It required manufacturers to list on the label the proportion of alcohol, opium and morphine included in the product. It also banned cocaine from such remedies. Although it did not limit public access to these products, it did help wary consumers avoid taking opiates by mistake.

So by 1908, most habit-forming medicines were under some form of control. What remained uncontrolled, however, were drugs intended for specifically non-medical use.

The Opium Act attempted to fill this gap. Recall that the law targeted opium “for non-medical uses.” It was aimed at what we now call recreational drug users.

King himself was actually not unfamiliar with opium in its medical, recreational and habit-forming states. As a law student, he attended police court, where he encountered addicted criminals. In the 1890s, he purchased opium for his sick brother; he also had an opium-addicted friend who ended up in a Toronto asylum.

These are all indications that King had a wide knowledge of opium’s baneful influences. But the focus on King fails to recognize that change comes through a convergence of forces.

At the same time that King was heading to Vancouver to issue reparations, prominent Methodist minister Samuel Dwight Chown was already there, on the encouragement of Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, to investigate opium smoking.

Among other things, Chown described in correspondence with Laurier the concerns expressed by members of what he called the “better class” of the Canadian Chinese community about opium smoking among their compatriots living in Canada.

Was lack of debate on the Opium Act also evidence that the measure solely targeted Chinese in Canada? Not necessarily considering the broader parliamentary process and the fact that MPs were highly familiar with the issue of opium use.

Since the PPMA had been discussed repeatedly over three years, they did not need to revisit the issue. Opium’s baneful influences were indeed very well-known.

The Opium Drug Act

Although opium smoking was a habit enjoyed by some Chinese, King claimed it was not exclusively a Chinese problem. White “bohemians” were also reportedly fond of opium.

In 1911, concerns about non-medical drug use were consolidated into the Opium and Drug Act. It broadened the substances restricted for non-medical use to include morphine and cocaine, and increased the penalties for trafficking.

These are the foundations of Canada’s drug laws. They were built on decades of increased restriction, first at the provincial level and later at the federal. They embodied concerns about how legitimate medicines were being flaunted by people seeking a thrill, escape or palliation.

Some of these people were Chinese. Many of them were not.

More than 100 years later, this tension between legitimate/medical and illegitimate/non-medical use of drugs persists.