The Gallipoli centenary provides a unique opportunity to reflect on the many wartime legacies – human, political, economic, military – that forged independent nations from former colonies and dominions. The Conversation, in partnership with Griffith Review, has published a series of essays exploring the enduring legacies of 20th-century wars.

The term “history wars” is best known in Australia for summing up the fierce debate over the nature and extent of frontier conflict, with profound implications for the legitimacy of the British settlement and thus for national legitimacy today.

That debate, though hardly resolved, is now taking something of a back seat to a public controversy focused on Australia’s wars of the 20th century and particularly on the war of 1914–18, called the Great War until the Second World War redefined it as the First.

If “history war” is a public controversy about past events that raise disturbing contemporary questions about national legitimacy and identity, then this Great War controversy also qualifies as such. The polemic unfolded in a familiar fashion. “History warriors” from the political right have publicly insisted that historians and left-wing commentators were distorting the past and violating cherished understandings about the First World War.

In various forums, they stated and restated their now-familiar case: Australia’s vital interests were at stake in the Great War and it took part to protect these interests. The warriors insist there is a left-wing “orthodoxy” arguing that Australia’s national interests were not served by participating in the war and that Australians were duped by the British into fighting.

The recent past and the present loom large in the warriors’ anxiety. They insist that Australia is not in the habit of sending troops overseas to fight “other people’s wars”, as critics suggest, and that participation in overseas wars throughout the 20th century (and since) has been overwhelmingly in Australia’s interests. They have loudly condemned, and continue to condemn, historians and journalists who see this differently.

Broadsides along these lines have been heard for a generation. I’m not certain where it started, but an early shot fired in Quadrant in July 1982 by columnist Gerard Henderson merits closer inspection. Henderson was unhappy with the then-emerging field of social history and its emphasis on “waste” and suffering, because – in his view – it undermined the rightness of the cause.

Henderson targeted the distinguished social historian Bill Gammage, whose celebrated “emotional history” of the war, The Broken Years, was based on soldiers’ diaries. Gammage was guilty, Henderson claimed, of distinguishing “between the Anzacs as individuals and the cause for which they fought” – of feting the soldiers but condemning the war. Gammage was a consultant on the Peter Weir film Gallipoli wherein the same distinctions were evident, and equally odious, to Henderson.

Henderson stated his belief that the war was right for Britain and Australia. He took issue with the notion of the war as tragedy:

The Great War was “futile” and a “waste” in one sense only – in that the Western Allies in the 1920s and 1930s surrendered much of what had been won in 1914–1918 due to their all-embracing guilt.

So the tragedy “in one sense only” is to be found in foreign policy errors made after the war. Had these errors not been made, nothing about the Great War would be tragic, “futile” or a “waste”. This, presumably, is the hard-nut indifference to suffering (even on a massive scale) that is required by the men of high politics.

But I find this interesting for another reason.

At the time, Gammage was researching and writing social history, or “history from below”. He was determined to show how this war was experienced by ordinary people and to document their terrible ordeals on the field of battle and, yes, the horrendous waste of human beings, talent and potential.

Australian history probably followed literature here, for it was a novelist who put the human legacy of war on the national agenda. George Johnston’s bestselling novel My Brother Jack was published to great acclaim in 1964. The novel explored the disastrous impact of war for a single family on the home front. It opened up a national conversation about the true legacy of war. Gammage picked up the baton and ran.

In this capacity, Gammage was a part of – or more accurately ahead of – a cultural shift in the history business, with a newfound concern for the traumatic impact of war experience right across the wars of the 20th century, and thereafter.

Historian Christina Twomey wrote about this shift in the December 2013 edition of History Australia. Twomey argued that social history’s focus on suffering in war is but one part of a fascination with the traumatic in contemporary society. She called this change “the rise to cultural prominence of the traumatised individual” and argued that this rise is not peculiar to Australia, or even to the military sphere, but is evident throughout the Western world.

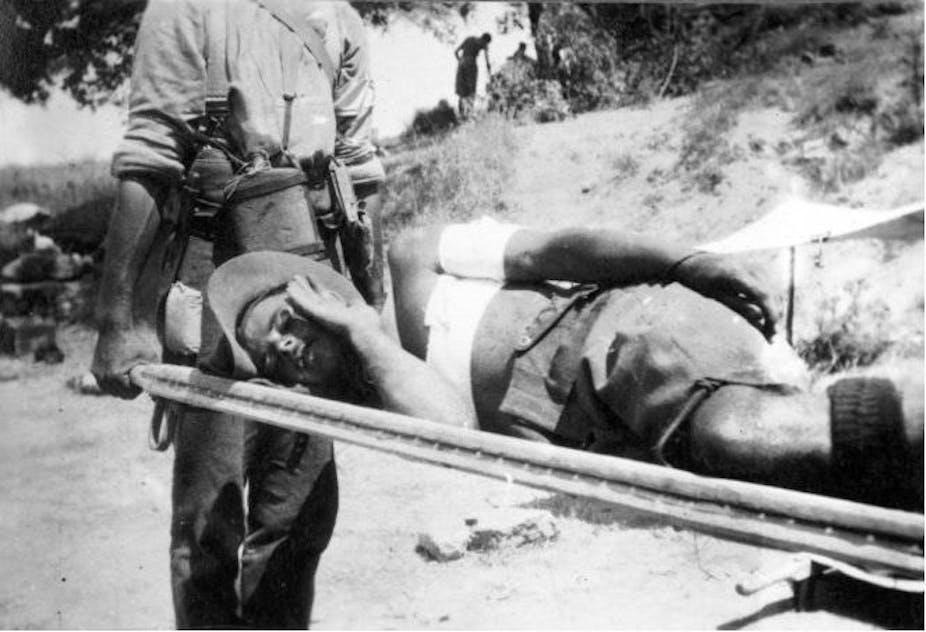

In this vein, though years earlier, Gammage explicitly rejected the label “military history” for The Broken Years. He wrote “to show the horrors of war”. The book has never been out of print and trauma is now a field of study in Australian history, with titles such as Joy Damousi’s Living with the Aftermath: Trauma, Nostalgia and Grief in Post-War Australia, Stephen Garton’s The Cost of War: Australians Return and Peter Stanley’s Lost Boys of Anzac, among others. But this new focus is perhaps best summed up by Marina Larsson’s Shattered Anzacs: Living with the Scars of War.

In her article, Twomey concludes that the “trauma” perspective – this understanding of what war does to people – has been the principal reason for the resurgence of enthusiasm for the Anzac tradition. No doubt there’s some truth in this idea of a congruence between the personal and the political, empathy working to bind people together in solemn tribute to our nation’s military endeavour over a century and more. But it’s a shaky foundation.

A military heritage understood as trauma and suffering will always threaten to undermine narratives constructed around strategic necessity. Tragedy can too easily extend to critical evaluation of the political necessity for war, both then and now. To emphasise the human side of the war might even break the airlock that shields high politics and belligerent journalism from such considerations.

Perhaps this tension is behind one of the oddities of the current “history war”: never has the Anzac tradition been more popular and yet never have its defenders been more chauvinistic, bellicose and intolerant of other viewpoints. One only has to read the Murdoch press editorials, features or op-eds on Anzac Day (or thereabouts), or the polemics in Quadrant, to know this.

Every year the hard heads kick in – “we got it right”, they say – and serve up the summary analysis, column after column, never failing to fire a shot or two at the doubters, the usually unnamed “orthodox” school that peddles the fiction of “other people’s wars” or “futility”.

New inclusiveness but a greater intolerance

ANU historian Frank Bongiorno has argued that it is precisely the renewed cultural authority of Anzac – the popular enthusiasm for remembrance – that has had unanticipated and, for some of us, unwanted consequences, notably a declining toleration of any critique of Australian military endeavour.

In an edited collection, Bongiorno charts how Anzac commemoration has changed in recent times. Ethnic groups and Aboriginal people claimed a part or a familial connection in one or another of Australia’s wars across the 20th century – somewhat like Australians finding a link to a convict ancestry and with it a newfound pride in their national identity.

There is now a small wing of Australian publishing that is busy with books about German Anzacs and Irish Anzacs, Black Diggers, Ngarrindjeri Anzacs, Chinese Anzacs, Russian Anzacs and so on.

The new inclusiveness is one of a number of causal factors underpinning the resurgence of enthusiasm for the Anzac tradition. There is, also, the metaphysical pull of the occasion – the obstinate or perhaps eternal need for the sacred in a secular society. There is the rise of genealogy, linking families to forebears who fought and suffered and died for us. There is the progressive broadening of criteria for participation in the marches.

And there is the all-important role of governments (Labor and Liberal) in the lavish promotion of a war-centred nationalism going back at least to the Hawke government.

It has been noted, for instance, that Anzac Day works better as a national day because it avoids the contentious matters that Australia Day brings to the fore – Aboriginal dispossession and colonisation.

So, Anzac’s popularity is on a high and, buoyed by this popularity, the ideological guardians of the tradition seek to press home their advantage. As Bongiorno points out:

There is a long history of contention over the significance and meaning of the Anzac legend. But once a tradition is defined in more inclusive terms, those who refuse to participate can readily be represented as beyond the pale. To question, to criticise – to doubt – can become un-Australian.

The vitriol has been warming for some time. An editorial on April 26, 2013, in The Australian is instructive. It had suggestions for the bureaucrats responsible for organising commemorative events in the centenary years to come:

The best advice we can offer is that they ignore the tortured arguments of the intellectuals and listen to the people, the true custodians of this occasion. They must recognise that the current intellectual zeitgeist is at odds with the spirit of Anzac. It recognises neither the significance of a war that had to be fought nor the importance of patriotism. Honour, duty and mateship are foreign to their thinking. They may be experts on many things, but on the subject of Anzac, they have little useful to say.

Two days later, Andrew Bolt chimed in on cue in the Herald Sun. Intent on vilifying academic critics of the Anzac legend, he suggested they were lining up with Islamic extremists. He named two respected scholars – Marilyn Lake and Clare Wright – and suggested that their expertise had abandoned them on matters Anzac. Doubt and debate in Bolt’s worldview is not only unpatriotic, it is the mark of fanaticism and treachery.

Now the Great War centenary has arrived and the history warriors have chosen their weapons. Paul Kelly set the tone in August 2014, when he railed in The Australian that Australians had been mugged by an anti-war mythology. The film Gallipoli got another blast, as did:

… the legacy of poets and “anti-war cultural practitioners” who, since the 1960s, have peddled the lie, the “delusion”, that the Great War was a terrible blunder … that saw millions sacrificed in vain.

In Quadrant, the busiest critic of late has been Mervyn Bendle, an untiring polemicist. His concerns run entirely contrary to the historical project – he wants the Anzac past to be fixed and sacred. He thinks the issue here is “respect for Australian society”, and describes critical interventions in military history as:

… an elitist project explicitly dedicated to destroying the popular view of these traditions.

The agents of this conspiracy are at one time “little more than a pampered coterie” and elsewhere a more considerable force (one assumes), since they are:

… led by a cadre of academics, media apparatchiks and some disaffected ex-army officers.

Bendle seems entirely uncomfortable with the vigorous, contested nature of the discipline. He caricatures these rival interpretations as “an iconoclastic holy war against the Anzac tradition”, and in one instance as “a jihad”. Quadrant has published Bendle’s denunciations regularly since 2009.

Bongiorno’s take on such intemperate reaction is well put:

Anzac’s inclusiveness has been achieved at the price of a dangerous chauvinism that increasingly equates national history with military history, and national belonging with a willingness to accept the Anzac legend as Australian patriotism’s very essence.

But if the new inclusiveness of Anzac commemoration provides backing for this kind of intolerance, it is also true that the centenary (now with us) has heightened anxieties about the legitimacy of the so-called Great War, as has the widespread questioning of recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The context for intolerance has, in this sense, been overdetermined.

The debate is not closed elsewhere

In the past two decades, as the centenary has crept up, the scholarly contest around the origins and the meaning of the Great War has intensified. The anniversary has lifted the game to a new intensity – nowhere more evident than in Britain, where historians and politicians have eagerly put their case. Some of the most intemperate interventions seem designed to caricature critical reflection and shut down debate.

Michael Gove, then British education secretary, set the tone in January 2014 when he tore into “left-wing academics” for peddling unpatriotic “myths”. He cited satire such as Rowan Atkinson’s Blackadder as grist to the left-wing mill that encouraged these myths and denigrated the “patriotism, honour and courage” of those who served and died.

The bizarre edge to Gove’s intervention suggests a fear that the contest may not be going his way. As Oxford professor Margaret MacMillan put it:

He is mistaking myths for rival interpretations of history.

Gove had tried to enlist MacMillan to his cause, referring favourably to her important (if oddly titled) book, The War That Ended Peace. But MacMillan said he got it wrong:

I wish we could see understanding the First World War as a European issue, or even a global one, and not a nationalistic one.

Good advice.

The history business is more richly resourced, sophisticated and nuanced, more exhaustive and rigorous and more openly scrutinised by a fascinated general public than ever before. A vigorous contest about the origins and meaning of the war continues unabated.

Broadly, two schools of thought have been contesting the ground at least since A.J.P. Taylor’s War By Timetable. One insists Germany was hell-bent on world domination and had to be stopped. The other (including Taylor) sees the great powers as collectively responsible in varying ways and to varying degrees.

And inextricably tied into these two schools are views set on a spectrum between “high and noble purpose” and ghastly “futility”.

The complexity of this debate should not be understated. My grasp of it suggests the “collective responsibility” school of thought is far more soundly based in history than the nationalistic “evil Germany” version. Perhaps the best example of this headway is Christopher Clark’s celebrated volume The Sleepwalkers.

Clark is an Australian, and now a professor of modern history at Cambridge. His delightfully readable account of the polarisation process that led to war teases out this collective responsibility against a background of ethnic and nationalistic ferment in Europe at the time. He writes:

The outbreak of war is not an Agatha Christie drama at the end of which we will discover the culprit standing over a corpse in the conservatory with a smoking pistol.

Clark sees smoking pistols in many hands. He sees a Europe in which all the great powers were pursuing their own interests, willfully indifferent to the interests of others and, to that end, ready to risk a major conflict, having no idea of the horrors they were about to unleash.

The point is this: the debate in Britain is not closed. It is perhaps more wide-open than ever and well able to resist the forces that would shut it down and render history into a hammer in the sectarian tool box.

An elite ‘hell-bent’ on war

In Australia, the scholarly scene is similarly robust and, one trusts, similarly resistant to bullying and coercion. Here, too, the coming of the centenary has heightened critical scrutiny and a reactive anxiety that insists the past is sacred.

While social historians continue to track the personal cost of our wars among soldiers and their families, and the cultural industry produces countless books, movies, TV series and tours of battlefields, a more political line of inquiry has in recent times tracked the “militarisation of Australian history” since the 1980s.

The evidence of this obsession is found in patterns of government funding, in the media, publishing and education, in documentaries and electronic media programs devoted to the history of Australians at war – to the detriment of our many other pasts. The imbalance here has dire consequences for the breadth and depth of understanding of the past, as Henry Reynolds has pointed out:

The implications fly off in all directions – nations are made in war not in peace, on battlefields not in parliaments; soldiers not statesmen are the nation’s founders; men of blood are more worthy of note than negotiators and conciliators; the bayonet is mightier than the pen; a few fatal days on the shore of the Ottoman Empire outweighed the decades of civil and political pioneering by hundreds of colonial Australians.

The centenary has galvanised this concern with numerous authors, several key titles and website Honest History raising the critical standard. In What’s Wrong with Anzac?, edited by Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds, the contributing scholars sought to explain how this obsession with military history has been manufactured and to highlight how it eclipses a rich and diverse history of nation-making, civil and political traditions of democratic equality and social justice.

It must be said that the book has sparked fierce criticism from within the history community. Distinguished scholars Inga Clendinnen and Ken Inglis contested the “top down” explanation of the resurgence of Anzac and others pointing to misapprehensions about “propaganda” being fed into schools and about both teachers and students as passive recipients. But there is much in the book that merits attention. It set out to provoke discussion and debate. In that, it has been entirely successful.

Other scholars have indirectly shaped the critique of the obsession with Anzac by contributing to a broadly conceived cultural history that places Asia (and thus our racial anxieties) at – or near – the centre of our national story. Australia’s Asia, edited by David Walker and Agnieszka Sobocinska, is a key text in this regard. Within this framework it has become possible to rethink Australia’s entry into the Great War, notwithstanding the voices that insist there’s nothing more to know.

A number of authors have taken up this challenge, notably John Mordike and recently Greg Lockhart, who charted the secret commitments that shaped Australia’s entry into the war and the racial fears that motivated Australian politicians to make these commitments. Mordike, Lockhart and Walker, and predecessors such as historian Neville Meaney, have reshaped the way we think about the racial frameworks that governed political thought and the fears that underpinned Australian defence policy leading up to the First World War – notably the obsession with Japan.

The great irony here is that Japan was a reliable British ally throughout those years of war – yet it was fear of Japan that drove White Australia’s commitment to an expeditionary war long before war broke out.

Another constructive contribution is Douglas Newton’s Hell-Bent. The title suggests the author’s revisionist perspective. Newton’s aim is to:

… interleave the story of Australia’s leap into the Great War and the story of the choice of war in Britain.

Newton’s interpretation sets Hell-Bent firmly in the collective responsibility camp, with Australian government intent – if not impact – as culpable as Britain and the rest. Newton’s book surveys the obsession with racial fitness, the post-Federation longing for blooding in battle, the searching for confirmation of racial virility and the almost universal belief that the one true test of national vigour was war.

Newton quotes Australian prime minister Joseph Cook’s diary of Monday, August 3, 1914 – the same day that he promised the Royal Australian Navy and 20,000 troops to Britain:

The good to come, [the] moral tonic. Luxury, frivolity and class selfishness will be less. A memory for our children, bitter and bracing for many.

Cook’s earnestness was at least preferable to Churchill’s effervescing glee at the prospect of war in July 1914, and his enjoyment of war thereafter. He could still call it “delicious” in January 1915.

War as socially uplifting and purifying was a common theme among Australia’s political elites in 1914. War was an antidote to “effeminate thinking”, ‘sentimentalism" and the way that too long a peace “can rot all manly thought and action out of our race”, as Melbourne academic Archibald Strong put it. War was a curative. War was a way to rescue the British race from the brink of destruction.

Such were the attitudes that underpinned a political elite “hell-bent” on war. The celebrants today would have us forget this. They would have us forget both the racial framework and the obsessive paranoia that inspired the push to war in Australia.

They would have us forget the lessons, too. In Gallipoli: a ridge too far, edited by Ashley Ekins, historian Robert O’Neill describes how “blindness and miscomprehension” about Turkey’s ability to defend itself was repeated in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan:

How strange it is that Winston Churchill, a voracious student of military history, thought that a force of some 60,000 men, backed by the Royal Navy, would rapidly induce a Turkish collapse leading to the seizure and occupation of Constantinople.

O’Neill goes on to note how the decision-making process was dominated by Churchill, and to record Charles Bean’s observation in The Story of Anzac – how through the:

… fatal power of a young enthusiasm to convince older and slower brains, the tragedy of Gallipoli was born.

Bean was the great official historian of the Australians in the First World War. He will be quoted liberally in the course of the centenary, but his blunt summary of the Gallipoli venture as a reckless fantasy may not get the attention it deserves.

No chance of that with James Brown’s Anzac’s Long Shadow, an unusual intervention that has stirred debate and critical reflection, and fury in the Quadrant ranks. Brown, a former officer who commanded troops in Iraq and served with Special Forces in Afghanistan, was the military fellow at the Lowy Institute when the book was published. He writes:

This year an Anzac festival begins a commemorative program so extravagant it would make a sultan swoon.

Brown argues that Australia is spending too much time, money and emotion on the Anzac legend at the expense of current serving men and women. He rejects the sophistry that suggests any criticism of the Anzac myth is anti-military. He also provides a sharp critique of the clubs and corporations that exploit the Anzac theme for commercial gain.

Brown does not dwell on the particulars of Australian involvement in the Great War but he does stress the importance of informed memory, of knowing Gallipoli for what it was:

A century ago we got it wrong. We sent thousands of young Australians on a military operation that was barely more than a disaster. It’s right that a hundred years later we should feel strongly about that.

In history, nothing is sacred

Politicians and a retinue of warrior commentators want us to be proud of our martial history, lest the nation fall apart. Historians worth their salt want us to know that history critically, lest the nation be deceived, or simply dumbed-down.

This is a great divide. History is a cautious, ever-questioning discipline, well aware that all historical truth is contextual and contingent and thus open to revision or to new ways of seeing the past. Politics is a profession played out with dogmatic certainties that are wielded like baseball bats. Where historians must be ever critical, ever ready to go deeper, politics – and national history as set down by politicians – must be unimpeachable.

Drape “Anzac” over an argument and, like a magic cloak, the argument is sacrosanct. History will not stand for that. In history nothing is sacred. History is open inquiry; politics is slogans.

Australia’s finest historian, Inga Clendinnen, explained the great divide between politics and history in the following way:

The discipline of history demands rigorous self-criticism, a patient, even attentiveness, and a practiced tolerance for uncertainty. It also requires that pleasure be taken in the epistemological problems which attend the attempt to recover the density of a past actuality from its residual traces. These are not warrior virtues.

Political agendas require a national story that is simple, fixed and inviolable. Thus the Anzac centenary is committed to locking in a glorious military past but, like the 1988 Bicentennial, it is raising more questions than the celebrants want. Centennials can backfire. That is the heart of the problem for the history warriors on the conservative side of politics.

That, more than any other factor, explains their bellicose insistence on the rightness of what happened.

You can read a longer version of this article and others from the Griffith Review’s latest edition on the enduring legacies of war here.