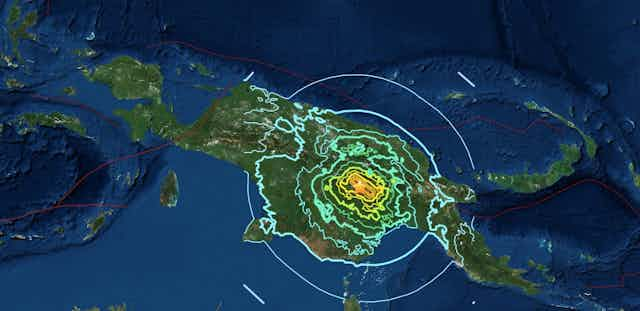

A magnitude 7.5 earthquake struck the Southern Highlands region of Papua New Guinea on February 25, 2018. This was followed by a series of aftershocks, producing widespread landslides that have killed dozens and injured hundreds. The same landslides have cut off roads, telecommunications and power to the area.

The PNG government has declared a state of emergency in the region. There is growing concern over several valleys that have been dammed by landslides and are beginning to fill with water - now ready to collapse and surge downstream, directly towards more villages.

Why is Papua New Guinea so susceptible to landslides? It’s a combination of factors - steep terrain, earthquakes and aftershocks plus recent seasonal rains have created an environment that is prone to collapse.

Read more: Five active volcanoes on my Asia Pacific 'Ring of Fire' watch-list right now

How land becomes unstable

The Earth around us is generally pretty stable, but when the ground shakes during an earthquake it can start to move in ways we don’t expect.

Pressure changes during an earthquake create an effect in the soil called liquefaction, where the soil itself acts as a fluid.

When lots of water is present in the soil, as is the case now during the monsoon season in Papua New Guinea, liquefaction can happen even more easily.

When liquefaction occurs, the earthquake creates changes due to friction. Imagine a visit to the greengrocer, where an accidental bumping of a carefully stacked pile of apples can cause cause them all to suddenly collapse. What was holding the pile together was friction between the individual apples – and when this disappears, so does the pile.

In an earthquake, two tectonic plates slip past one another deep underground, rubbing together and cracking the nearby rocks. The effects of this movement up at the surface can vary depending on the nature of the earthquake, but one feature is fairly common: small objects bounce around. The sand grains just below the surface do the same thing, but a bit less excitedly. A few metres down, grains could be bouncing around just enough to lose contact with each other, removing the friction, and becoming unstable.

Things are normally stable because they’re sitting on top of something else. When that support suddenly disappears, things tend to fall down – this is the classic dodgy folding chair problem experienced by many.

In engineering, we call this “failure” – and in the building industry it usually occurs immediately before the responsible engineer receives a call from a lawyer. Mechanically, this failure happens when the available friction isn’t enough to support the weight of the material above it.

Read more: Explainer: after an earthquake, how does a tsunami happen?

When soil acts like fluid

Once a slope fails, it starts to fall downhill. If it really slides, then we’re back to the same situation of grains bouncing around. Now, none of the grains are resting against each other, and the whole thing is acting like a fluid.

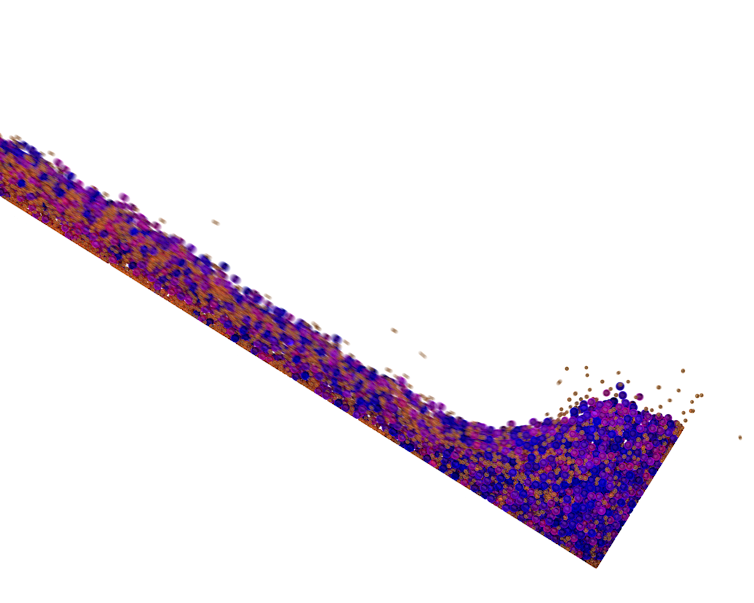

A couple of interesting things happen at this point. First, as the grains are bouncing around, small particles start to fall through all the newly formed holes that have opened up. This occurs for the same reason that you find all the crumbs at the bottom of your cereal box, and all of the unpopped kernels at the bottom of your bowl of popcorn. Once these smaller fragments accumulate at the bottom of the flowing landslide, they can help it slide more easily, accelerating everything and increasing its destructive power.

Second, landslides typically flow faster at the surface than below, so as large particles accumulate at the top they are also the ones moving the fastest, and they start to collect at the front of the landslide. These large particles, often boulders and trees, can be incredibly damaging for any people or structures in their path.

The image above shows a laboratory simulation of a landslide flowing down a slope and hitting a fixed wall. The spherical particles are coloured by size (small is yellow; large is blue). Data from these sorts of studies can help predict the forces that an object will feel if it gets hit by a landslide.

Watching and waiting

These complex dynamics mean that we really need to know a lot about the geography and geology of a particular slope before any kind of reliable prediction could be made about the behaviour of a particular landslide.

In the remote areas of Papua New Guinea, accumulating this data at every point on every slope is a tough challenge. Luckily, huge advancements have recently been made in remote sensing, so that planes and satellites can be used to extract this vital information.

Using sophisticated sensors, they can see past foliage and map the ground surface in high resolution. As satellites orbit quite regularly, small changes in the surface topography can be monitored. Scientists hope that by using this information, unstable regions that haven’t yet failed can be identified and monitored.

Read more: Controversial artist Elizabeth Durack gave us a sensitive insight into the lives of Papuan women

Papua New Guinea is located on an active fault line and has had nine major earthquakes in the past five years. Combined with the often remote and steep terrain, together with a monsoon season that delivers repeated heavy rainfall events, it is a particularly active area for landslides to develop.

The dry season in Papua New Guinea will not arrive until June. During the current wet season we may see even more slopes fail due to destabilisation by the recent earthquakes.