The Great Southern Australian Coastal Upwelling System is an upward current of water over vast distances along Australia’s southern coast. It brings nutrients from deeper waters to the surface. This nutrient-rich water supports a rich ecosystem that attracts iconic species like the southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) and blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus brevicauda).

The environmental importance of the upwelling is one reason the federal government this week declared a much-reduced zone for offshore wind turbines in the region. The zone covers one-fifth of the area originally proposed.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of a research publication that revealed the existence of the large seasonal upwelling system along Australia’s southern coastal shelves. Based on over 20 years of scientific study, we can now answer many critical questions.

How does this upwelling work? How can it be identified? Which marine species benefit from the upwelling? Does the changing climate affect the system?

Where do the nutrients come from?

Sunlight does not reach far into the sea. Only the upper 50 metres of the water column receives enough light to support the microscopic phytoplankton – single-celled organisms that depend on photosynthesis. This is the process of using light energy to make a simple sugar, which phytoplankton and plants use as their food.

As well as light, the process requires a suite of nutrients including nitrogen and phosphorus.

Normally, the sunlight zone of the oceans is low in nitrogen. Waters deeper than 100m contain high levels of it. This deep zone of high nutrient levels is due to the presence of bacteria that decompose sinking particles of dead organic matter.

Upwelling returns nutrient-rich water to the sunlight zone where it fuels rapid phytoplankton growth. Phytoplankton production is the foundation of a productive marine food web. The phytoplankton provides food for zooplankton (tiny floating animals), small fish and, in turn, predators including larger fish, marine mammals and seabirds.

The annual migration patterns of species such as tuna and whales match the timing and location of upwelling events.

Read more: Australian endangered species: Southern Bluefin Tuna

What causes the upwelling?

In summer, north-easterly coastal winds cause the upwelling. These winds force near-surface water offshore, which draws up deeper, nutrient-enriched water to replace it in the sunlight zone.

The summer winds also produce a swift coastal current, called an upwelling jet. It flows northward along Tasmania’s west coast and then turns westward along Australia’s southern shelves.

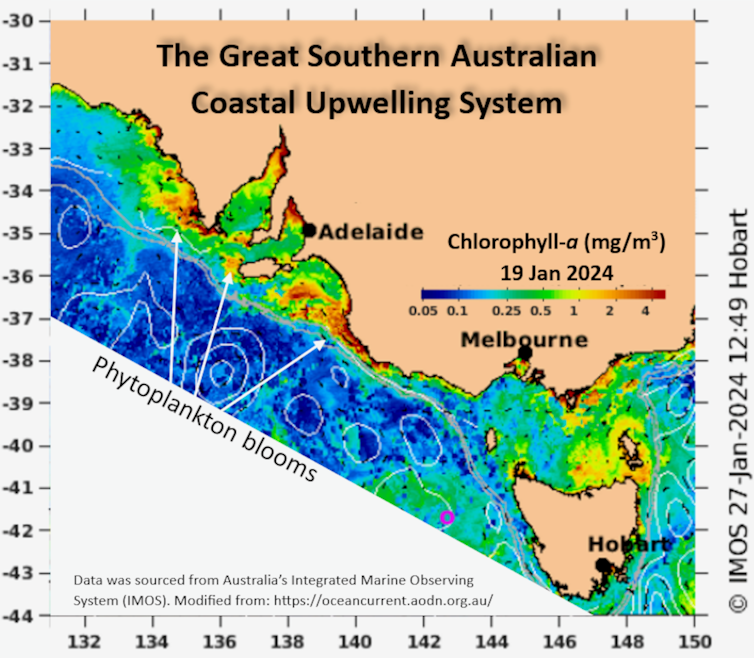

Satellites can detect the areas of colder water brought to the sea surface. Changes in the colour of surface water as a result of phytoplankton blooms can also be detected. This change is due to the presence of chlorophyll-a, the green pigment of phytoplankton.

From satellite data, we know the upwelling occurs along the coast of South Australia and western Victoria. It’s strongest along the southern headland of the Eyre Peninsula and shallower waters of the adjacent Lincoln Shelf, the south-west coast of Kangaroo Island, and the Bonney Coast. The Bonney upwelling, now specifically excluded from the new wind farm zone, was first described in the early 1980s.

Coastal upwelling driven by southerly winds also forms occasionally along Tasmania’s west coast.

Coastal wind events favourable for upwelling occur regularly during summer. However, their timing and intensity is highly variable.

On average, most upwelling events along Australia’s southern shelves occur in February and March. In some years strong upwelling can begin as early as November.

Recent research suggests the overall upwelling intensity has not dramatically changed in the past 20 years. The findings indicate global climate changes of the past 20 years had little or no impact on the ecosystem functioning.

What are the links between upwelling, tuna and whales?

The Great Southern Australian Coastal Upwelling System features two keystone species – the ecosystem depends on them. They are the Australian sardine (Sardinops sagax) and the Australian krill (Nyctiphanes australis), a small, shrimp-like creature that’s common in the seas around Tasmania.

Sardines are the key diet of larger fish, including the southern bluefin tuna, and various marine mammals including the Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea). Phytoplankton and krill are the key food source for baleen whales. They include the blue whales that come to Australia’s southern shelves to feed during the upwelling season.

Read more: Why scientists need your help to spot blue whales off Australia’s east coast

Unlike phytoplankton and many zooplankton species that live for only weeks to months, krill has a lifespan of several years. It does not reach maturity during a single upwelling season. It’s most likely the coastal upwelling jet transports swarms of mature krill from the waters west of Tasmania north-westward into the upwelling region.

So the whales seem to benefit from two distinct features of the upwelling: its phytoplankton production and the krill load imported by the upwelling jet.

Seasonal phytoplankton blooms along Australia’s southern shelves are much weaker than other large coastal upwelling systems such as the California current. Nonetheless, their timing and location appear to fit perfectly into the annual migration patterns of southern bluefin tuna and blue whales, creating a natural wonder in the southern hemisphere.