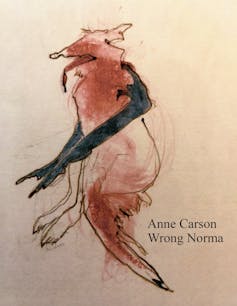

Wrong Norma, the latest collection of writings (and drawings and facsimiles) by the feted Canadian poet Anne Carson, is a work full of allusions, quotations, references, parody and other forms of stylised evocation.

Sometimes the allusions are more buried than a quick Google allows for. The opening piece 1=1, for instance, is a meditation on (among other things) swimming. While considering all the swimmable bodies of water that are not being swum in, the narrator eccentrically asserts:

One by one or all at once, geographically or conceptually, putting aside gleaming Burt Lancaster, someone should be using all that water.

Out of context, with its campy imperative tone and reference to a mid-century movie star, this could almost be from a poem by the New York poet Frank O’Hara. But the narrator of 1=1 quickly moves on to a more contemporary concern: “refugees in a makeshift plastic boat” – one of a number of references in Wrong Norma to political, ethical or legal concerns.

Review: Wrong Norma – Anne Carson (Jonathan Cape)

But what of Burt Lancaster, whose presence seems enigmatic compared to the morally urgent maritime asylum seekers?

Lancaster played the lead role in The Swimmer (1968), an adaptation of a story by John Cheever, in which the protagonist seeks to “swim home” across the backyard pools of well-heeled Connecticut. This quasi-surrealist conceit, which brings together the real and the gently fantastic, is an appropriate allusion for Carson’s book, which also inhabits the liminal spaces between everyday reality and the extra-rational categories writers traffic in: the lyrical, the surreal, the absurd, and so on.

At the risk of freighting a fleeting reference with undue significance, The Swimmer – a film about the loss of romantic and social bonds – also seems thematically apposite for Wrong Norma, as each piece in the collection is concerned with connection and its opposite.

Disconnection might seem, at first glance, to be the work’s modus operandi. The book is made up of a diverse, seemingly unrelated, series of forms and genres: short stories, poems, essays, lectures, dialogues, translations, satirical vignettes and elegies.

These formally diverse pieces are also conspicuously heterogeneous in their subject matter. The author describes the collection as being

about different things, like Joseph Conrad, Guantánamo, Flaubert, snow, poverty, Roget’s Thesaurus, my Dad, Saturday night, Sokrates, writing sonnets, forensics, encounters with lovers, the word “idea”, the feet of Jesus, and Russian thugs.

Random, as a teenager in the noughties might have said.

But this apparent randomness is given a degree of form by various connections, intended or otherwise. Certain images and phrases reappear, so that they begin to act like motifs. Sure, these images and phrases might themselves appear random – they include bread, weeping, the crossing of legs, foxes, tuna, Virginia Woolf and John Cage – but that is how repetition works. Things, from the insignificant to the culturally resonant, take on importance when they reappear.

By engaging in these acts of connection (that is, noticing the momentary linking of apparently disparate things), the reader apprehends the tension between connection and disconnection as an overarching theme of the book.

Other related themes start to make themselves apparent. The thematisation of dialogue, conversation, sentences, translation and language more generally, is ultimately concerned with language’s (and therefore our) ability to make or not make connections between the self and the world, the self and others. These connections – as the buried allusions, apparent non sequiturs, eclectic subject matter and sudden shifts of tone suggest – are not facile or inevitable. As the narrator states in 1=1 (the redundancy of the title being redolent of both meaning and meaninglessness), “Conversation is precarious”.

Precarious play

According to the psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott, play – of which creativity is a “higher” expression – is also precarious. This precarity is most obvious when a writer abandons, destroys or does not publish work. But we can see it, too, in the subjective experience of reading, which is the vicarious sharing in the play of another.

Such a “connection” is not inevitable, as made clear by the handful of times when I felt bored and alienated by Carson’s rambling, sometimes opaque narratives. But for the most part, her pieces are oddly compelling. Her status as a poet is underlined by moments of imagistic brilliance, such as the description, in An Evening with Joseph Conrad, of a church congregation: “Everyone sat packed like teeth.”

In the noirish Eddy, intense moments of lyricism appear out of nowhere: “Calm as linen is the lab at night, lamps on, black winter beating the windows.” Later in the same piece, Carson includes this wintry tableau:

She looks out her [car] window at a man wrestling three enormous snowflakes out of a box onto his lawn, beside him a plastic snowman tilts on a mound of snow. Man gives her a look. The wires of his snowflakes are terribly tangled. Inside a dark house a dog is barking, barking.

And then there is Carson’s gift for humour and the strategic pricking of literary seriousness. I especially like her paraphrase of a sentence about creativity from Samuel Beckett’s story The End (1946): “Build a little kingdom then shit on it.”

The ghost of Beckett haunts this collection, not least in Lecture on the History of Skywriting, in which the sky (suitably personified) interviews Godot, that non-appearing presence from Beckett’s landmark play Waiting for Godot (1953). It is a characteristic Carson gag that Godot’s first name should turn out to be Rusty. “So tell me, Rusty,” asks the sky, “how did it all get started, the non-arriving?”

Not arriving, not connecting, is a common feature of this collection: not arriving at a conclusion; not arriving at a meaning; not arriving at the expected destination, and so on. Such non-arrivals, Carson seems to be reminding us, are central to the artistic process.

Tragedy and enigma

Humour and linguistic skill are strong tools for a writer, and I read Wrong Norma primarily for its comedy and images. But tragedy and enigma are present too, especially with regard to capital-H History.

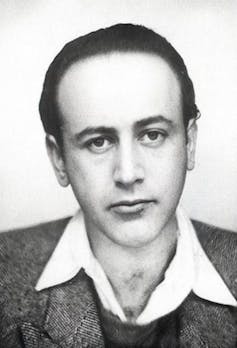

One of the strangest pieces in Wrong Norma, Todtnauberg, concerns the meeting in 1966 between the German philosopher Martin Heidegger (“a committed Nazi from 1933 until who knows when”) and Paul Celan, the Romanian-born French poet and Holocaust survivor who wrote in German.

Carson’s poem is named after Celan’s poem about the meeting, a piece that in turn was named after the village in the Black Forest where the meeting took place. At some level, Carson’s poem seems to evoke the ancient argument between philosophy and poetry, which is consistent with the numerous evocations of classical themes and figures throughout Wrong Norma and Carson’s work as a whole – she has had a long career as a professor of Classics.

Carson’s Todtnauberg employs an extreme form of parataxis – a poetic technique that uses juxtaposition without explanation – in response to Celan’s poem, which is similarly paratactic and enigmatic in style.

Misread as a homage by Heidegger and his students, Celan’s Todtnauberg has been the subject of extensive critical and biographical debate. Carson’s intervention in this debate appears wilfully short and almost simplistic, with its childlike, frankly ugly, drawings and apparent linking of the meeting between the philosopher and poet with Celan’s suicide in 1970.

Dialogue and misunderstanding, image and narrative, the sayable and the unsayable: Todtnauberg is perhaps the most intense expression of the theme of (dis)connection in Wrong Norma, which is perhaps why I was haunted for days by the question of its import – aesthetic as much as moral.

In her 2004 Paris Review interview, Carson offers a kind of key to her work when she repeats a maxim from the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan: “The reason we go to poetry is not for wisdom, it is for the dismantling of wisdom.”

Carson’s career has been one of dismantling and reassembling the forms, traditions and texts that she finds fascinating. She is engaged in an ancient dialogue between writers across time and space. Her oeuvre as a whole is one of connection as much as disconnection.

But her work, with its semi-random use of association and coincidence, also seems to evoke a more mundane and contemporary form of connection and disconnection. The internet, as much as literary history, could be an analogue for her work, in the way that it collapses time and space into instantaneous and seemingly infinite connections and disconnections.

As such, I wonder if there is a risk that the virtual worlds of writers such as Carson might start to seem a little less strange, a little less absorbing, when their aesthetic has become virtually (in both senses of the word) routine. Perhaps, but at its best, Carson’s routine – to use the word in its stand-up comedy sense – is indeed nothing less than compelling.