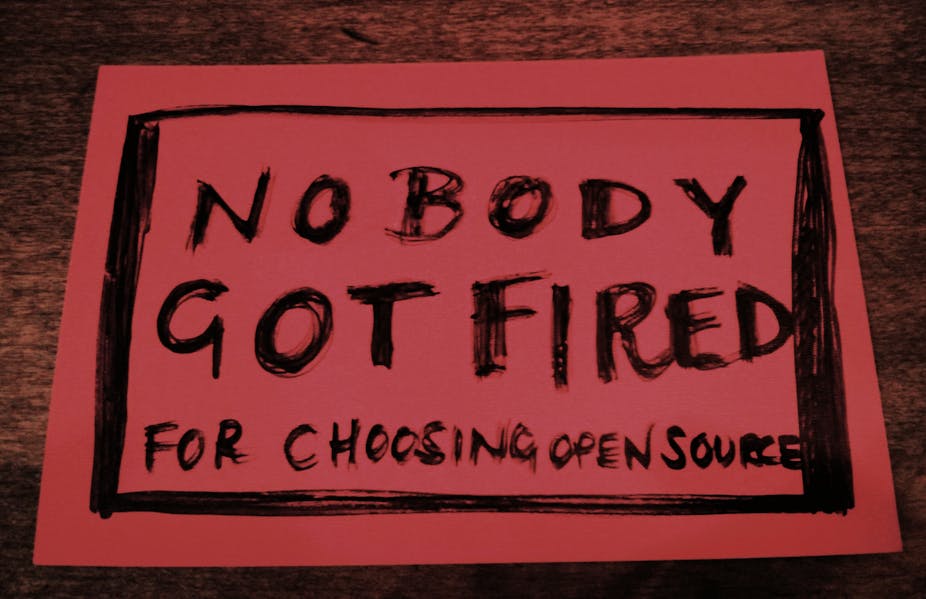

The UK government has revealed that it is considering ditching Microsoft software for open source alternatives. Cabinet minister Frances Maude has said he wants to see a range of software being adopted by the thousands of civil servants that work across departments and believes that this could save millions. Indeed, since Maude spoke out on the matter, it has been suggested that the government has spent more than £200 million on Microsoft products since 2010 alone.

Maude isn’t the first to realise that vast amounts of public money is spent on computer programmes that could be found for free. Even with bulk discounts, setting up thousands upon thousands of civil service computers with Microsoft software is a real drain on finances.

The adoption of open source software has been going on in the European public sector since the early 2000s. In a first phase, OpenOffice was trialled in public administrations in Italy, Germany, England, Ireland, Germany, Belgium, Denmark and Hungary, but just at the local level, with little co-ordination.

In a second phase, several European projects tested out the wider use of open source projects, including OpenOffice. This included replication studies, evaluation of costs of ownership and sharing of best practices.

Advocates and users of open source software have identified several advantages to using it instead of Microsoft suites. It costs nothing to licence (whereas Microsoft software comes with a hefty price tag) and it is easy to install and use. The very nature of open source software means that its standards – the way it is implemented – must be open and reproducible. And, crucially, it is easy to convert between formats, so you can still retrieve and use old Microsoft documents after making the transition.

On the other hand, the main argument against using OpenOffice is its total cost of ownership. Although you don’t have to pay Microsoft for the product and associated support, you still need consultants to do that support. It also costs money to train your staff in the new software, even if it is easy to use, and converting between formats is not flawless – largely because the Microsoft format is not based on open standards.

There is also an ongoing debate over the security and trustworthiness of open source software. Advocates believe that security flaws and errors are fixed more easily in open source. All the software is visible to everyone, so experts around the globe will fix any incumbent flaws as they come up.

Opponents, meanwhile, argue that the open standards are the very reason open source software should not be used. Malicious users will exploit flaws since they too have complete access to the code. However, the alternative, “security via obscurity”, has been criticised for being ineffective. It’s not as though Microsoft is immune to viruses and malware.

The spread

Open source software has traditionally been linked to experts and technologists. They enjoy its functionality and can cope with the fact that it is less easy to use than commercial products. This is generally what holds non-experts back from taking the plunge.

But like OpenOffice, a number of open source projects have become much more usable over the past decade. They are also much more stable than they used to be, meaning that they work properly, for longer, without crashing. Larger organisations can feel more comfortable adopting them for all staff without worrying that an unexpected bug will prevent an entire department from working for a whole afternoon.

There is also more support available than ever before. Online forums offer solutions to problems and the more well known open source providers host sites themselves.

This started with open source browsers such as Netscape, which later became Mozilla and then Firefox. Then office suites like OpenOffice and LibreOffice and emailing systems like Sea Monkey, Opera and Thunderbird followed suit until, finally, complete operating systems such as Ubuntu and Fedora became infinitely more accessible to the masses.

Now virtually any proprietary software that you might use at home or work has an open source counterpart. In design, AutoCAD can be replaced with FreeCAD, to play media content, VLC is free and easy and when you want to automate tasks like accounting, inventory and orders, paid-for SAP software can be replaced by Compiere. Even antivirus software can be found in open source form.

Ready to switch?

There are two basic criteria that the UK government should consider before switching to open source. And the same applies to anyone else thinking of making the change. First, and most obviously, it needs to decide if the software offers the functionality it needs. This is quite likely the case in this day and age.

The second, though, is the “sustainability” of the open source project being considered for use. Open source projects are ultimately developed by online communities, so it’s important to assess that community. Is it active in developing new features for the software? Is support provided to users in a reliable way? Is there a commercial organisation among the developers of the software, which might imply that they think it worth spending time and money on?

All these factors are important if the software is to be usable over the long term and can make the whole process more cost effective. And that’s just as important as functionality.

Maude has made the right choice in looking into alternatives to expensive proprietary software, all it will take is a little homework in advance to get it right. It’s a symbolic step that could really benefit the movement and would vastly increase the visibility and awareness of free alternatives to the wider public.