Popular ideas about teenagers are often polarised: from lazy, immature school kids who love to wake up late, to threatening gangs of youths dressed in hoodies, to reckless children who need to be protected from their own stupid decisions. None of these descriptions are necessarily wrong – indeed, there are scientific explanations for some of these behaviours – but they do show how many conflicting ideas exist about teenagers in society.

My research investigates the language used by journalists and lawyers to describe one particular group of adolescents: those who come into contact with the law – whether in a criminal or family law setting. It’s complicated, but looking overall, there are patterns in how young people are described, which can clarify what otherwise seems like a mass of contradictions.

Young people are dangerous

On Whitsun weekend in 1964, hundreds of teenagers from two opposing lifestyle groups - the Mods and the Rockers - vandalised shops and fought each other and the police in the seaside town of Margate. The media reaction was outrage and the magistrate who sentenced some of those involved described them as “long-haired, mentally unstable, petty little hoodlums”.

Yet when criminologist Stanley Cohen looked at the Mods v Rockers riots, he realised that the media had exaggerated the extent of the events. The language used in court and in the media had described this small number of teenagers, involved in minor acts of disorder, as representative of all young people.

Panics about young criminals and rebellious behaviour still occur today. From young people using social media to give themselves “points” for rival stabbings, to “phone obsessed teens” who put themselves at risk of ADHD, language has been used to create panic about young people. This moral panic is fuelled by media and mobilises popular opinion to the point that politicians change laws or policies in ways which are out of proportion to the real threat.

Young people need protection

Completely at odds with the idea that young people are a danger to society, is the idea that they need to be protected from it. Though teenage and adolescence are often thought of as a different life stage to childhood, UK law states that a person can only become an adult at age 18 – what’s called the age of majority.

Teenagers often make life-changing decisions well before this age – such as choosing a religion – but in extreme circumstances the law has the power to invalidate their decisions.

In family law courts, cases often arise to determine which parent a young person will live with, or whether they go into care. Yet there is still much dispute about whether teenagers should be allowed to express their opinion in court, or whether it would be too traumatic for them.

During the 1990s, there were a number of cases involving young people who were under 16 and seriously ill, but whose faith as Jehovah’s Witnesses meant that that they had religious objections to receiving blood products in hospital. All of them had their choice overruled by the courts, because they were judged not competent to make a life-ending decision. Ian McEwan’s novel The Children Act – now a film starring Emma Thompson – is based on precisely this scenario.

In one of the cases, the judge explained that a 15-year-old was incapable of making the decision, because he didn’t understand the manner of his death – though this was because his doctors had elected not to tell him. Both the court and his doctors were trying to protect him – even though it was that which stopped him from making an informed choice.

Young people are immature

Why can’t you get married until you’re 16, drive until you’re 17, and vote until you’re 18? The usual justification for these age limits is that they reflect the growing development of young people’s minds. There has been research to show that adolescents’ brains continue developing until well into their mid-20s. So this doesn’t fully explain why legal age limits are set where they are.

In a criminal trial involving a person under 18, there are various special sentencing options intended to rehabilitate the offender. Part of the official justification for this is that “children and young people are not fully developed and they have not attained full maturity”. But these sentencing principles are not always applied consistently.

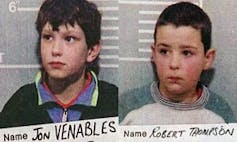

In the case of the killing of James Bulger in 1993 by two ten-year-old defendants, the judge echoed the media outrage surrounding the case, sentencing both defendants to indefinite detention in a secure unit and describing them as “both cunning and very wicked”.

But psychologists have since raised doubts about whether the defendants were truly mature enough to understand the wrongness of their crime - especially since one asked at the time whether James could be taken to hospital “to try and get him alive again”.

Seeing how language is used to describe children in contact with the law can reveal how our mental ideas of the “typical” teenager are formed. Yet one young person can often have multiple ideas projected on them at once – as exemplified by the case of the killers of Bulger. Ultimately, every one of these ideas about what young people is a simplification – a shortcut which enables adult society to form judgements without engaging with the complexities of life as a young person.

Spotting how these simplified patterns emerge – and the serious consequences they can have for young people’s lives – should encourage a healthy scepticism of the stereotypes about teenagers which exist in our society.