Over the past decade, the super-rich and large corporations have been able to borrow at record low interest rates. This influx of easy money has shored up markets for yacht-backed-loans and securities, dividends, share buy-backs, and merger and acquisition deals.

Meanwhile, those not deemed “creditworthy” find themselves barred from credit, the powerless witnesses of ever surging rents and living costs. Time and again, the financial sector has flooded certain parts of the economy while other parts remained parched. The question is: Why is it so hard to fix the money system?

Two parts of financial literacy

Lack of financial literacy among most citizens is at least one of the causes – though there are competing definitions of the latter. On 7 June, the European Commission (EC) lamented that “levels of financial literacy in the EU are too low”, posing a threat to “personal and financial well-being, households and society more broadly.”

However, here the institution takes a rather narrow view of financial education, limited to personal finance – i.e., teaching people how to manage budgets, achieve saving goals, and understand different financial products. Earlier in March, Sigrid Kaag, the Dutch Minister of Finance, echoed a similarly minimalist view of financial literacy: “By practising how to save, plan and make choices from a young age onwards, children learn how to make sound financial decisions.”

The other view of financial literacy, which we support, entails a far more ambitious understanding of the money system. We call it systemic financial literacy. “In the age of the CDS and CDO, most of us are financial illiterates”, wrote US financial journalist Matt Taibbi in 2009, referring to the complex financial products that triggered the Great Recession. Fast forward fourteen years later, and most of us remain unfamiliar with the jargon of economists, bankers and tax experts. As in 2009, today’s democracies continue to be divided into what Taibbi describes as a “two-tiered state, one with plugged-in financial bureaucrats above and clueless customers below.”

With this in mind, we believe any project seeking to boost financial literacy ought to educate us on the roles of a central bank, but also payment infrastructure, the tax regime, and the investment of our pension savings. A number of questions ought to be raised, too, to this end: What do we consider public utilities? Which financial services can better be assigned to private companies? Who gets the power to create and allocate new money – and for what purposes? To answer these big questions requires not only a deeper understanding of the structures of finance, but continuous political engagement.

The waterworks

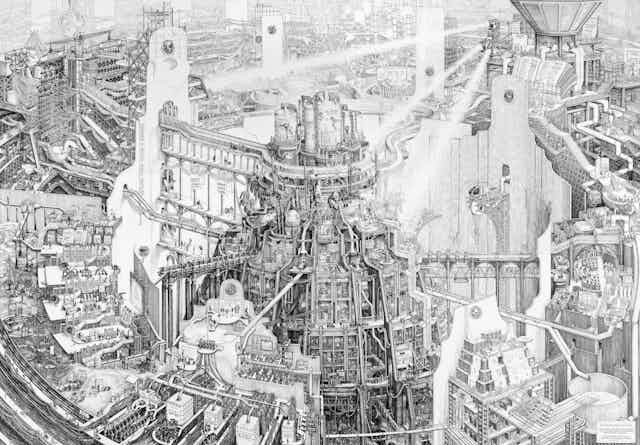

Together with cartographer Carlijn Kingma and investigative financial journalist Thomas Bollen, we sought to create a project that would inspire such questions and demystify the world of finance. For two and half years, we developed the “waterworks of money”, an architectural visualisation of our money system that bypasses the economic jargon.

Kingma spent 2,300 hours drawing this map by hand, based on in-depth research and interviews with more than 100 experts – from central bank governors and board members of pension funds and banks to politicians and monetary activists. In an animated video, we walk you through a metaphorical representation of our money system, its hidden power made manifest.

What do we water?

The metaphor of water was critical to the design of our map. Indeed, the financial sector is to the economy what an irrigation system is for farming lands. Just as irrigation helps crops grow, money allows the economy to flourish.

The architecture of our financial irrigation system and the way the sluices and floodgates are operated impacts us all. “What do we water, and what goes dry?” Kaag asked economists, bankers and reporters in June 2022. “Choices made by the financial sector determine what grows and what dies off. That’s where banks, pension funds, asset managers, and insurance firms can make a difference,” she said.

In our map, the long and complex process of financial irrigation starts at the top of the so-called tower of society, where big money keeps their reservoirs. The world’s largest companies, including big oil, big pharma and big retail, are lodged there. Open the floodgates and money flows downstream, setting the wheels of industry in motion. Salaries make their way through the waterworks, and trickle down into employee piggy banks. In return, everyone goes to work.

Money eventually seeps down into the lowest ranks of society, where the conveyor belt is always running, products are assembled and raw materials, mined. People then spend the wages they’ve earned, often in shops and businesses. Sale revenues get pumped up to the reservoir at the top, and the cycle starts all over again. Or at least, that is the idea.

In reality, the trickle-down economics popularised by US president Ronald Reagan and UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher, do not take place. Money circulates mainly between the top of the tower and the financial sector. Moreover, the huge growth of the financial sector over the last decades has dug the gap between the haves and have-nots deeper. The growing quantity of money is driving up share prices, house prices and management fees, but most of the money does not reach the everyday economy in the tower of society – where it can be used for productive investments, generates income and add social value.

The structure of our money system is not a natural phenomenon. The way the waterworks are put together is a political choice. In democracies, higher levels of systemic financial literacy are a prerequisite to change this architecture and make the financial sector serve society better.

This article was co-written with investigative financial journalist Thomas Bollen and cartographer Carlijn Kingma.