How cells become cancerous is a process researchers are still trying to fully understand. Generally, normal cells grow and multiply through controlled cell division, where old and damaged cells are replaced after they die by new cells. Sometimes this process stops working, leading cells to start growing uncontrollably and develop into a tumor.

Traditionally, cancer treatments like chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation and surgery focus on killing cancer cells. Another type of treatment using stem cells called differentiation therapy, however, focuses on persuading cancer cells to become normal cells.

We are researchers who study how stem cells, or immature cells that can develop into different types of cells, behave in states of health and disease. We believe that stem cells can provide potential treatments for cancer of all types in many different ways.

How do stem cells contribute to cancer?

Stem cells are unspecialized cells, meaning they can eventually become any one of the various types of cells that make up different parts of the body. They can replenish cells in the skin, bone, blood and other organs during development, and regenerate and repair tissues when they’re damaged.

There are different types of stem cells. Embryonic stem cells are the first cells that initially form after a sperm fertilizes an egg, and can give rise to all other cell types in the human body. Adult stem cells are more mature, meaning they can replace damaged cells only in one type of organ and have a limited ability to multiply. Researchers can reprogram adult stem cells, or differentiated cells, in the lab to act like embryonic stem cells.

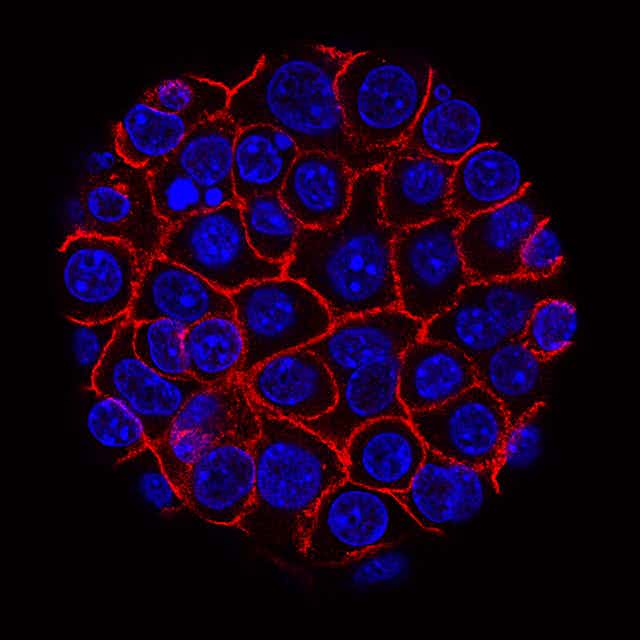

Because stem cells can survive longer than regular cells, they have a much higher probability of accumulating genetic mutations that can result in loss of control over their growth and ability to regenerate. This is why many tumors harbor a small subpopulation of cells that function like stem cells. These so-called cancer stem cells are thought to be responsible at least in part for cancer initiation, progression, metastasis, recurrence and treatment resistance.

What is differentiation therapy?

Accumulating evidence is also showing that cancer stem cells can differentiate into multiple cell types, including noncancerous cells. Researchers are taking advantage of this fact through a type of treatment called differentiation therapy.

The concept of differentiation therapy originated from scientists observing that hormones and cytokines, which are proteins that play a key role in cell communication, can stimulate stem cells to mature and lose their ability to regenerate. It followed that forcing cancer stem cells to differentiate into more mature cells could subsequently stop them from multiplying uncontrollably, making them become normal cells.

Differentiation therapy has been successful in treating acute promyelocytic leukemia, an aggressive blood cancer. In this case, retinoic acid and arsenic are used to block a protein that stops myeloid cells, a type of blood cell derived from the bone marrow, from fully maturing. By allowing these cells to fully mature, they lose their cancerous qualities.

Furthermore, because differentiation therapy doesn’t focus on killing cancer cells and doesn’t surround healthy cells in the body with harmful chemicals, it can be less toxic than traditional treatments.

Using stem cells to treat cancer

There are many other potential ways to use stem cells to treat cancer. For example, cancer stem cells can be directly targeted to stop their growth, or turned into “Trojan horses” that attack other tumor cells.

Quiescent cancer stem cells, which don’t divide but are still alive, are another potential drug target. These cells typically play a big role in treatment resistance for various cancer types because they are able to regenerate and avoid death even better than regular cancer stem cells. Their quiescent quality can persist for decades and lead to a cancer relapse. They are also challenging to distinguish from regular cancer stem cells, making them difficult to study.

Researchers can also genetically engineer stem cells to express a protein that binds to a desired target in a cancer cell, increasing the efficacy of treatments by releasing drugs right at the tumor. For example, mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow naturally migrate toward and stick to tumors, and can be used to deliver cancer drugs directly to cancer cells.

Stem cells can also be used to make organoid models, or miniature versions of organs, to screen potential cancer drugs and study the underlying mechanisms that lead to cancer.

Challenges in stem cell therapy

Although, stem cells hold numerous advantages in their use in cancer therapy, they also face various challenges. For example, many current stem cell therapies that aren’t used in combination with other drugs are unable to completely eliminate tumors. There are also concerns about stem cell therapies potentially promoting tumor growth.

Despite these challenges, we believe that stem cell technologies have the potential to open new avenues for cancer therapy. Integrating genetic engineering with stem cells can overcome the major drawbacks of chemotherapeutics, such as toxicity to healthy cells. With further research, cancer stem cell therapies may one day become part of the standard of care for many types of cancer.