The GM picks me up from the airport. I call him the GM because after the PNG Supreme Court ruled the Manus Island immigration detention centre illegal, this man was able to leave the prison and find work as the general manager of a lodge in Lorengau town. Behrouz Boochani has arranged for me to stay at that lodge.

The GM’s Manusian colleague and another refugee accompany him. Driving into town we see police blocking part of the road beside a school; some locals are dispersing, others are gazing over at a cluster of trees.

I find out afterwards that the body of Hamed Shamshiripour has just been discovered among those trees beaten and with a rope around his neck.

Hours later, I meet Behrouz for the first time at the central bus stop in Lorengau. I always imagined him holding his smart phone – an inseparable union. A Kurdish journalist, writer and refugee from Iran, Behrouz has been incarcerated on Manus for five years. Since the start of 2016 I have been translating his journalism, communicating with him through WhatsApp.

During this time, his phone has been a lifeline to the outside world. He has shot a film and written articles on it – texting them to those beyond the prison fences – and now his book, No Friend but the Mountains.

We greet each other as he finishes a phone call. Australia’s border regime has stolen prime years of his life – he is weary and famished, but proud, vigilant and resolute. This is despite having had nothing to eat all day, the heat and sweat, being traumatised at the loss of a friend and the responsibility of reporting and communicating with the Australian and international media.

Over some days we get to know each other personally for the first time, and I meet others and translate articles in response to this latest tragedy. Then after the intensity, stress and anger have faded a little, we begin reviewing the chapters of No Friend but the Mountains. I have already translated about 80%.

Behrouz began writing from the very beginning of his exile and incarceration; he persevered after his phones were confiscated twice and stolen once. I began translating in December 2016; for one year I translated as he wrote using his smart phone.

Behrouz had text-messaged parts from various chapters to Moones Mansoubi, his very first translator beginning in 2015 and a translation consultant on this project. She would sort the texts into chapters on his instructions. Mansoubi then emailed me the PDFs – each chapter was one long text message of between about 9,000 and 17,000 words.

As I was translating from Farsi to English, I consulted regularly with Behrouz through WhatsApp. He would often add sections and make changes.

My translation process also involved weekly sessions with either Mansoubi or Sajad Kabgani, an Iranian researcher living in Sydney. While I translated, Behrouz continued to finish the book while communicating with his friends and literary confidants, Janet Galbraith, Arnold Zable, Kirrily Jordan and Mahnaz Alimardanian in Australia, and the intellectuals and creative thinkers Najem Weysi, Farhad Boochani and Toomas Askari in Iran.

Here on Manus, Behrouz reads the Farsi while I check the English. We stop and discuss sections, meanings, nuances and changes; we also digress and explore ideas, symbols, stories and theories far beyond the pages of the text. Describing his thinking and writing process, he explains:

The book is a playscript for a theatre performance that incorporates myth and folklore; religiosity and secularity; coloniality and militarism; torture and borders…

The translation method requires a form of literary experimentation. And the process is a form of shared philosophical activity.

Read more: UN slams Australia’s human rights record

Trying to preserve the sentence structure when translating Farsi literature into English results in unnecessarily long and cumbersome passages. Literature written in Farsi mostly consists of sentences with many elaborate and varied consecutive clauses. The subject is at the beginning and the verb is usually placed at the end.

The patterns and flow of adjectival clauses, synonyms and poetic and cultural images and allusions enable Farsi readers to move smoothly through the extended sentences due to a combination of melody, imagination, anticipation and consolidation.

In English, the same chain of clauses within a sentence becomes too awkward to read, losing much of its rhythmic thrust. Splitting sentences into many smaller ones is helpful. It also reflects the disrupted and fractured subjectivity and modes of knowing of those who are imprisoned refugees.

Read more: For $70m, government gets off lightly, but settlement still highlights responsibility for Manus

In this book, political commentary and historical account meet philosophical and psychoanalytic examination; these are framed or supported by myth, epic and folklore from various traditions, particularly Kurdish, Persian and Manusian. It is an anti-genre. I call the style “horrific surrealism”.

In significant places, noun phrases and monikers are also capitalised to emphasise personhood and Farsi prose is translated into English verse. For instance:

Killing time involves a simple trick / Reach out and hold another sunset / Another one of the thousand-colour Manusian sunsets / Then, reach out and hold another night / Another one of the dark island nights / A futile cycle … / Night and day revolving / Under the shade of an old tree.

Behrouz and I had a mutual understanding; in fact, the translation team embodied a kind of collective intention or shared agency. Our literary and philosophical interpretations evolved throughout the process. But the shared goal from the start was to produce a visceral narrative, a riveting masterpiece that exposed one central aspect of the detention regime: systematic torture.

Behrouz Boochani will appear by video link at Melbourne Writers Festival on August 29.

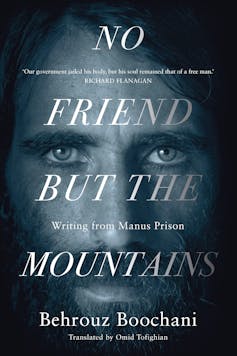

No Friend but the Mountains: Writing From Manus Prison is available in bookstores and online.